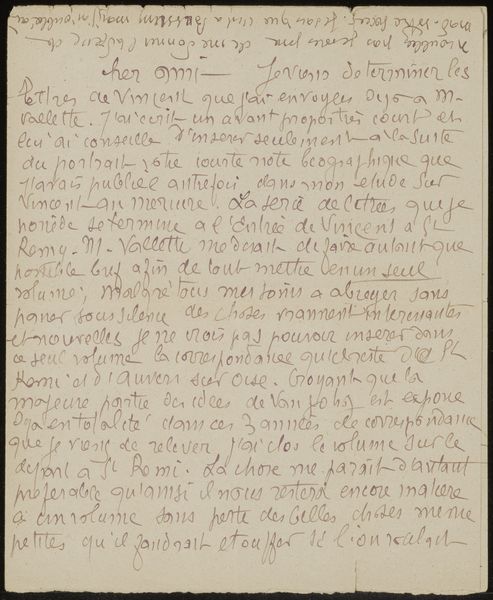

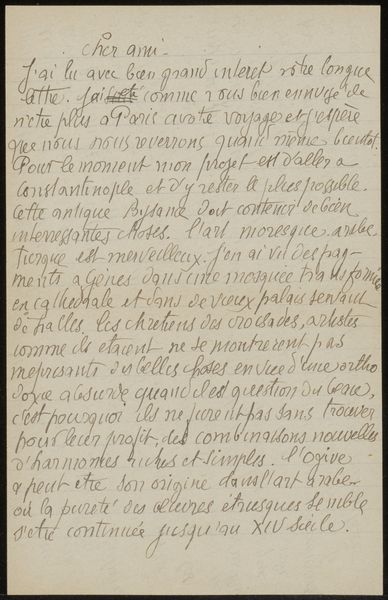

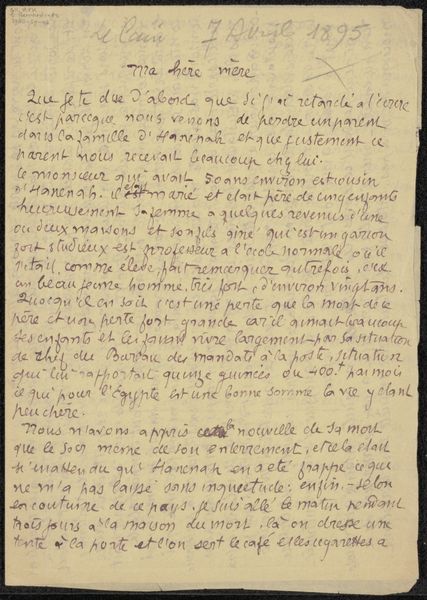

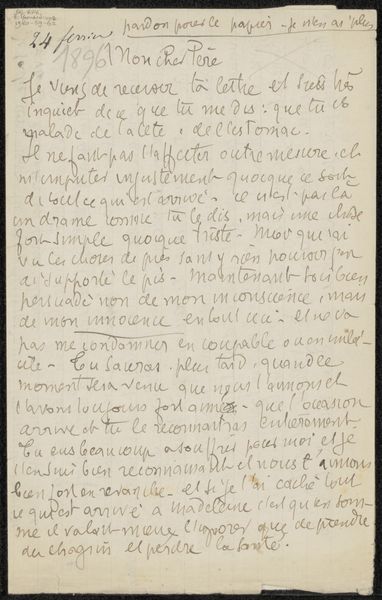

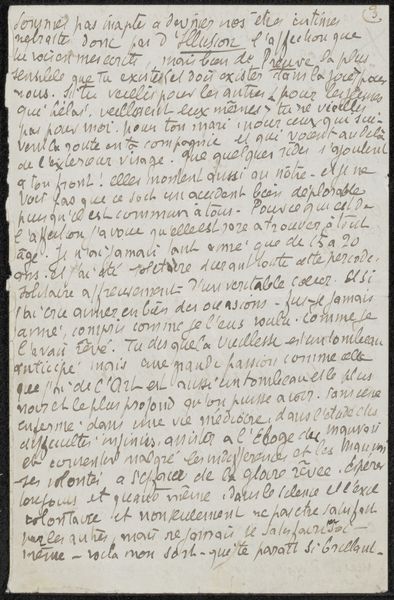

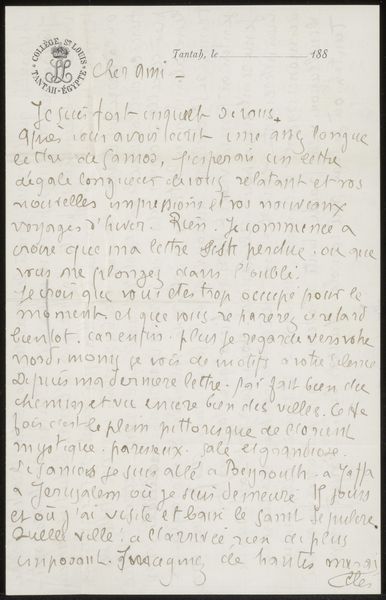

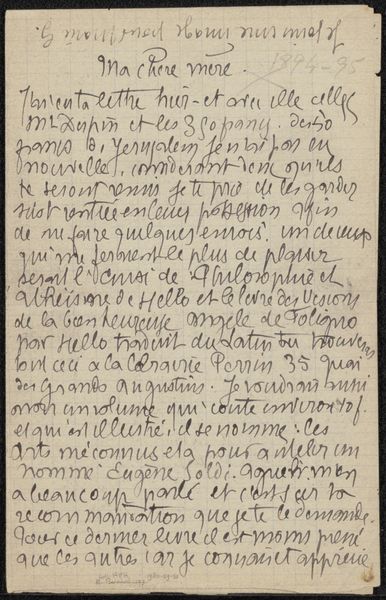

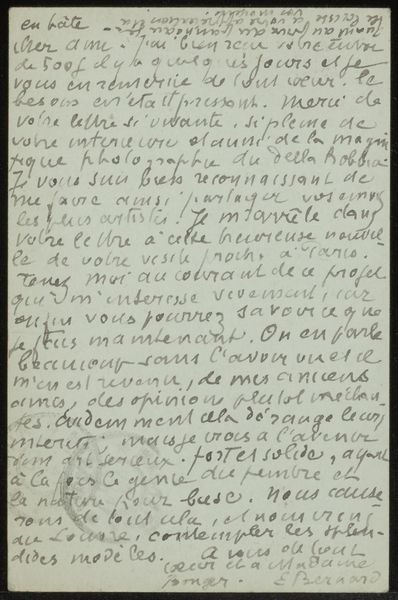

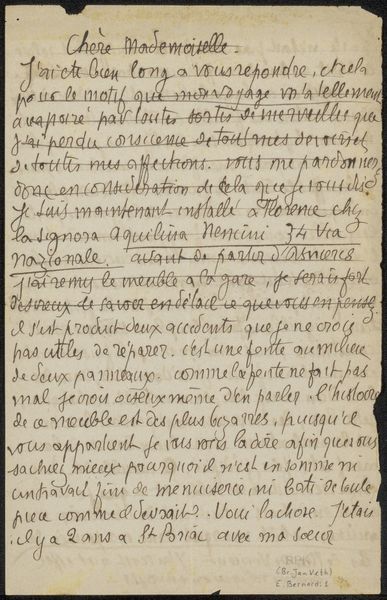

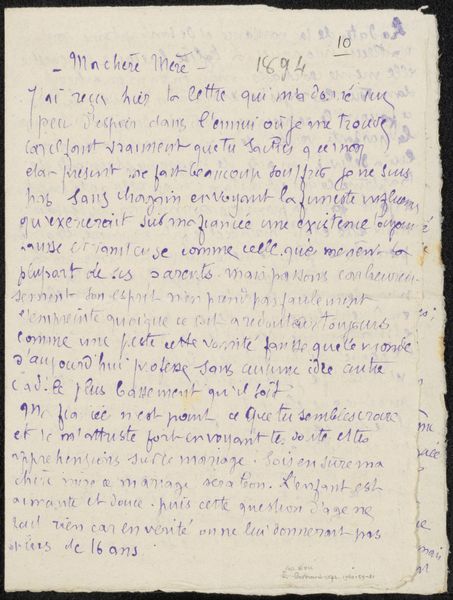

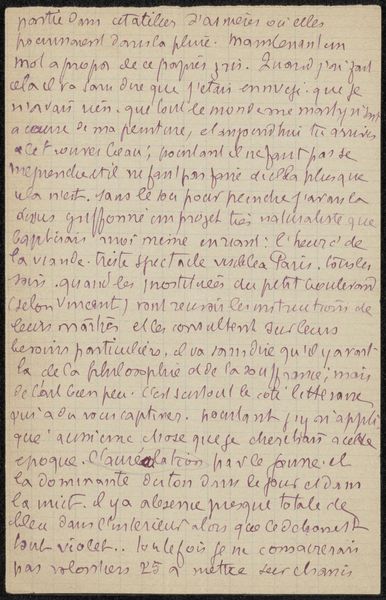

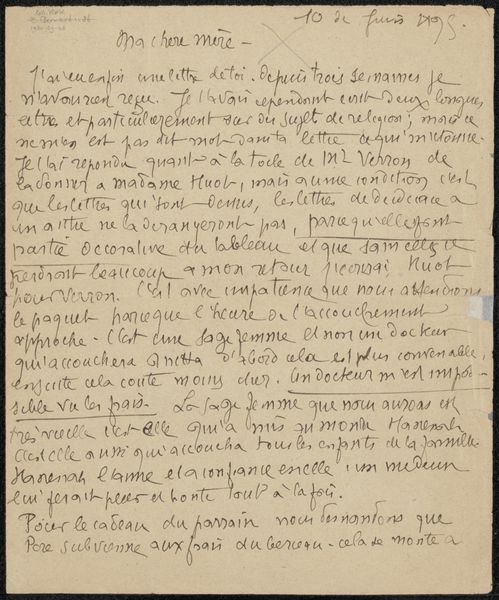

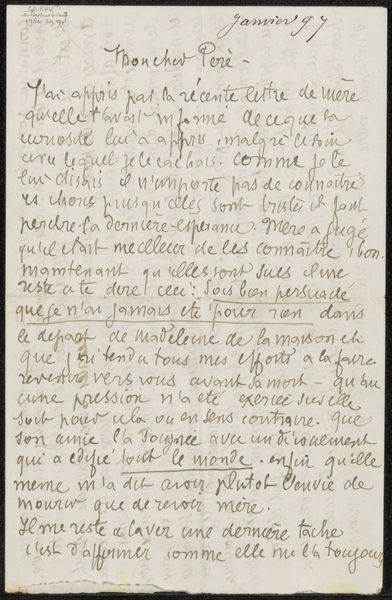

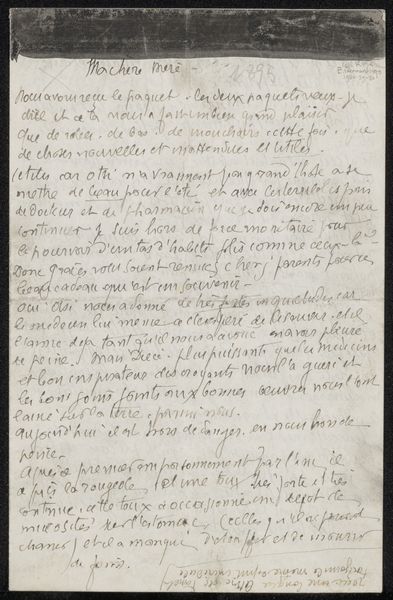

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

paper

#

ink

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at this—a letter from Emile Bernard, titled “Brief aan Héloïse Bernard-Bodin,” penned sometime between 1895 and 1896. It's an ink drawing on paper, quite intimate in scale. What's your immediate reaction? Editor: It feels incredibly private. The handwriting, that faded ink… It gives a sense of immediacy and perhaps a hint of the past that cannot be reclaimed. It's dense. Is that French? Curator: Indeed. Bernard is writing in French. We see how artists managed the daily realities, from money matters to preparing for exhibitions. Letters like this were obviously never meant to be artworks. Editor: True, it reveals aspects that official portraits and biographies often miss. Do you know the occasion that warranted this missive? Curator: It appears to be a candid rundown of the realities facing someone putting together an exhibition in Paris during that period. His style was influenced, in part, by Gauguin at this stage. Bernard was really striving, grappling with practicalities that even the most avant-garde artists couldn't escape. The fact that he jots all this down suggests to me it was a frequent thought in his head. Editor: Right, those nitty-gritty details matter. Who will show up? How will they understand my intention? That stuff's always in the artist's head. And also, I'd expect these thoughts were amplified in 1890s France—the place we most readily connect with artists pushing the bounds of representation! The letter provides a really specific window into a very culturally formative time and location. It almost feels like it gives one an insight into a cultural revolution in process, the letter as battlefield briefing, no? Curator: I completely agree. Beyond the surface level, it reminds us how artworks we consider transcendent are very often intertwined with daily life, with people’s struggles, and material realities. The beautiful thing is that its raw authenticity shines right through it! Editor: Definitely. It prompts us to reconsider our own preconceptions about who and where artists work, and the means by which the message becomes, simply, human, personal. This piece leaves us to see our commonalities more readily.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.