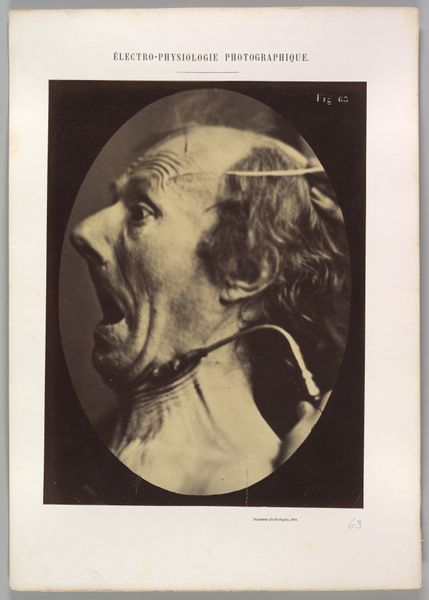

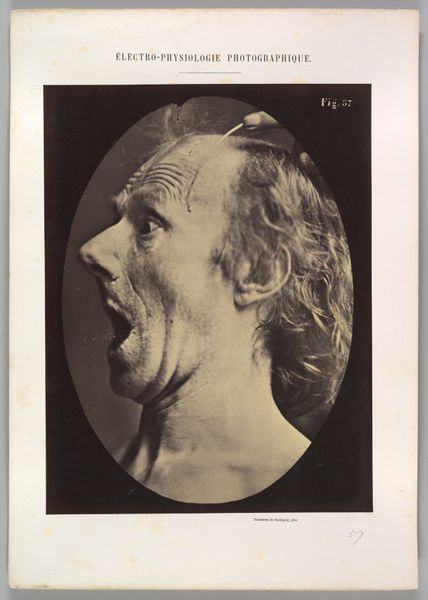

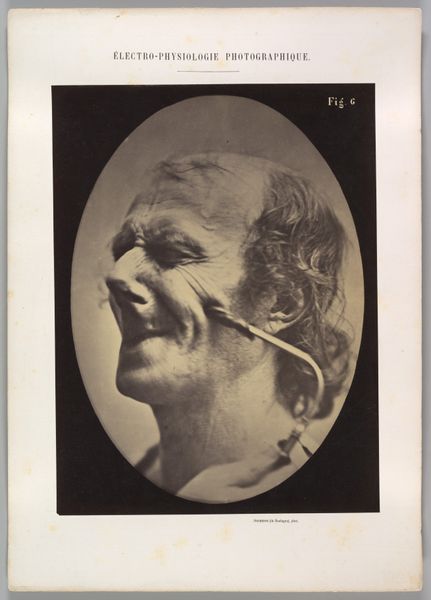

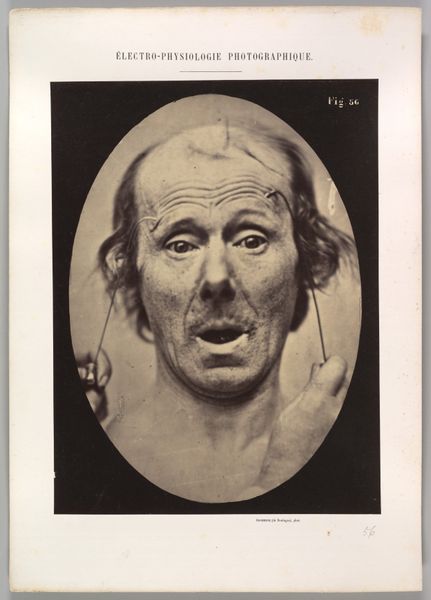

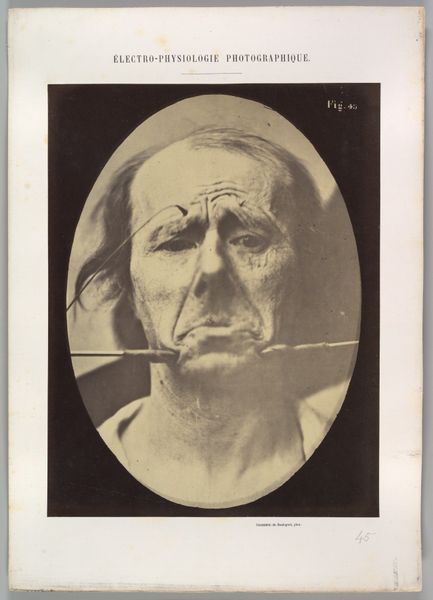

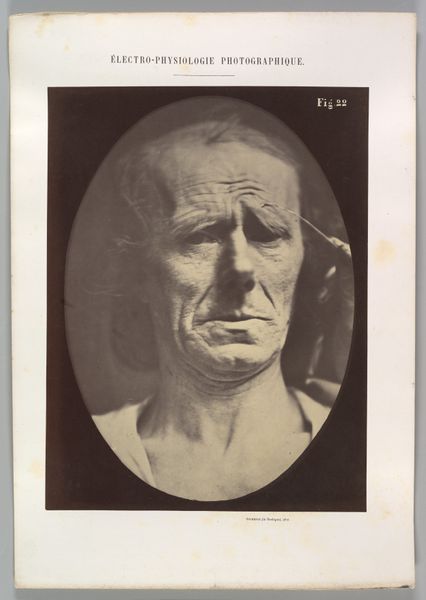

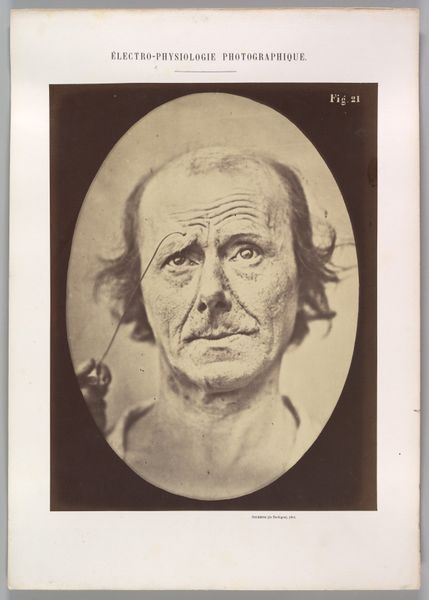

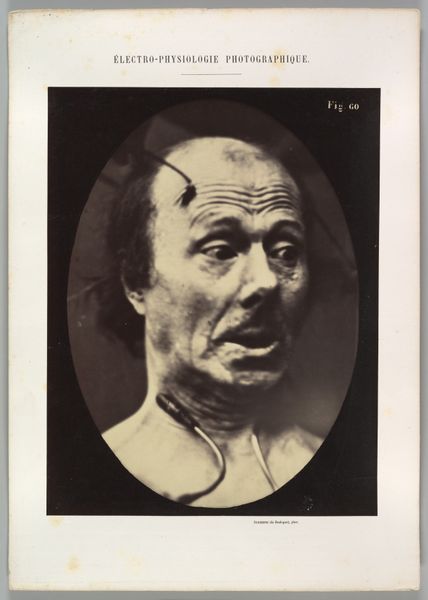

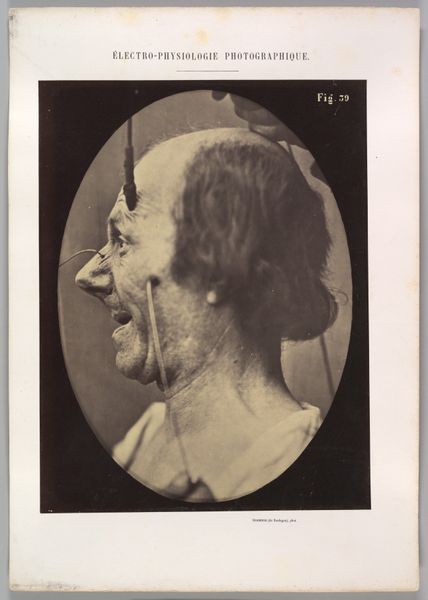

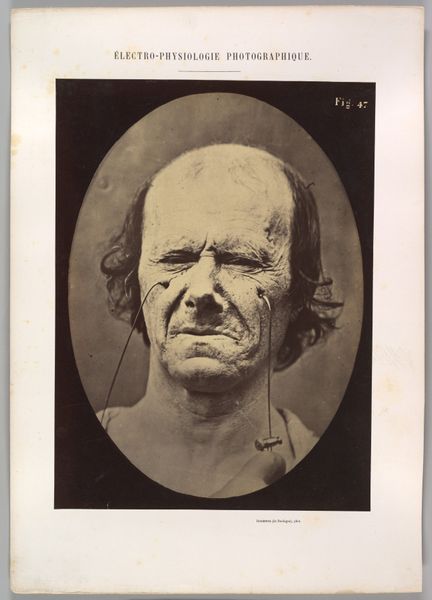

Figure 55: Astonishment badly rendered by the subject: a ridiculous and inane expression. 1854 - 1856

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Image (Oval): 28.3 × 20.4 cm (11 1/8 × 8 1/16 in.) Sheet: 29.8 × 23.1 cm (11 3/4 × 9 1/8 in.) Mount: 40.2 × 28.5 cm (15 13/16 × 11 1/4 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

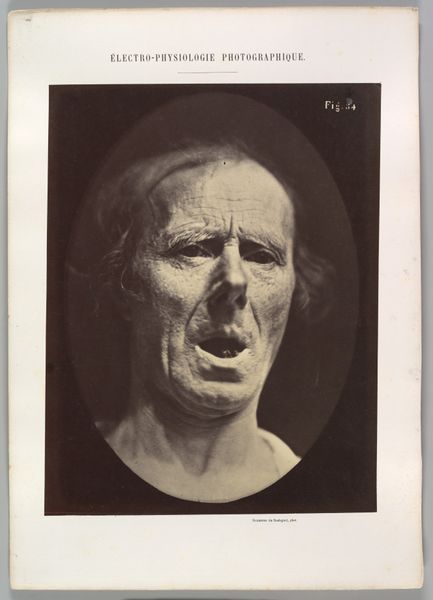

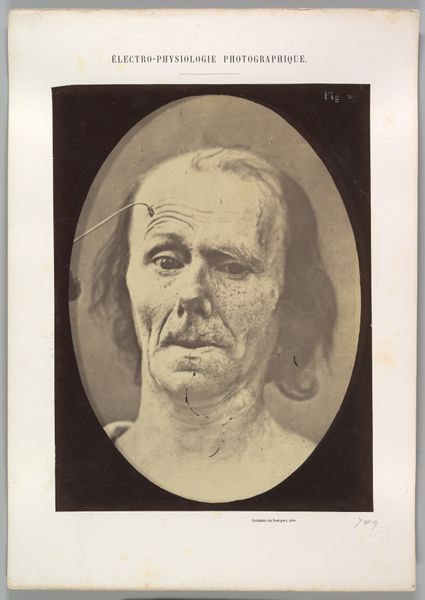

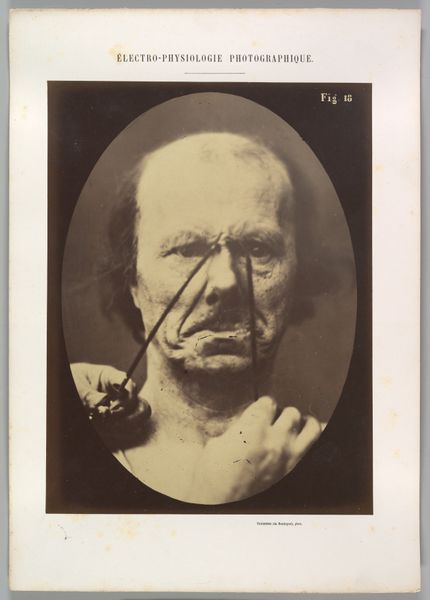

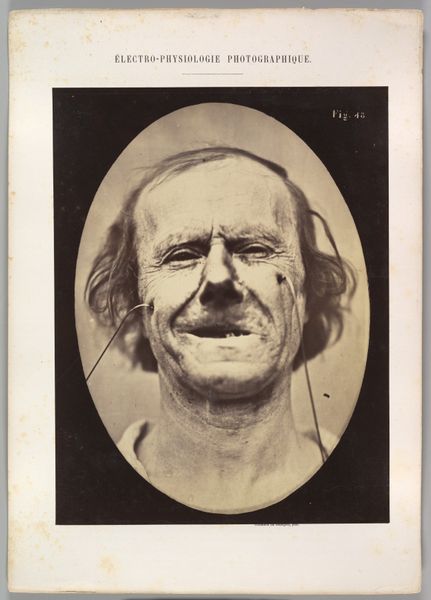

Curator: Before us we have, "Figure 55: Astonishment badly rendered by the subject: a ridiculous and inane expression," a daguerreotype by Guillaume Benjamin Amand Duchenne, dating from around 1854 to 1856. Editor: It’s stark, isn't it? The light seems almost aggressively highlighting every contour and fold of the man's face. There's something intensely unsettling about the asymmetrical planes, the way his mouth is agape… it feels performative, yet deeply vulnerable. Curator: Precisely. Duchenne's project was about codifying emotions, linking specific muscular contractions to universal expressions. It stems from a belief rooted in scientific positivism and a desire to categorize and control the subjective human experience. Editor: It seems reductionist. I’m struck by the social implications of reducing human emotion to mere physiology. It becomes a question of power, doesn’t it? Who gets to define what "astonishment" looks like and for whom? How is that leveraged, particularly within societal structures of inequality? Curator: Indeed. We need to question whose face gets to represent ‘astonishment.’ The subject, with his exaggerated expression and evident manipulation, becomes a kind of spectacle. Moreover, we cannot ignore the colonial context of these so-called scientific pursuits, linking phrenology and photography to reinforce problematic ideologies about race and class. Editor: Beyond that, the very materiality is striking— the reflective sheen of the daguerreotype, combined with the oval vignette, lends the photograph a disturbing surreal quality. The monochrome tonality and stark light contribute to a somewhat grotesque realism that is exaggerated, not subtle. Curator: His choice of daguerreotype, still a relatively new medium then, suggests that he wanted to capture scientific objectivity. He sees the camera as an extension of empirical observation. Duchenne's modernism intertwines uneasily with Romantic notions about humanity's relationship with reason and nature. Editor: Considering what we know, that this individual was likely an institutionalized patient subject to Duchenne’s electro-physiological experiments, brings an ethical burden. Are we complicit in his objectification merely by viewing this image? Curator: Absolutely, acknowledging our own position is paramount, ensuring we remain critically aware of power dynamics and ethical considerations. That includes understanding the harm done in pursuit of scientific advancement and progress, particularly for marginalized populations. Editor: I will say, I find myself questioning not only the photograph but photography as a medium of truth. Curator: It asks us to constantly interrogate the relationships between representation, knowledge, and power. This photograph remains a complex and disturbing testament to those relationships.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.