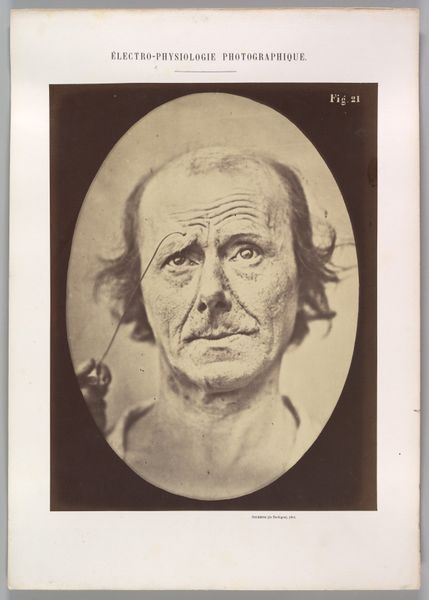

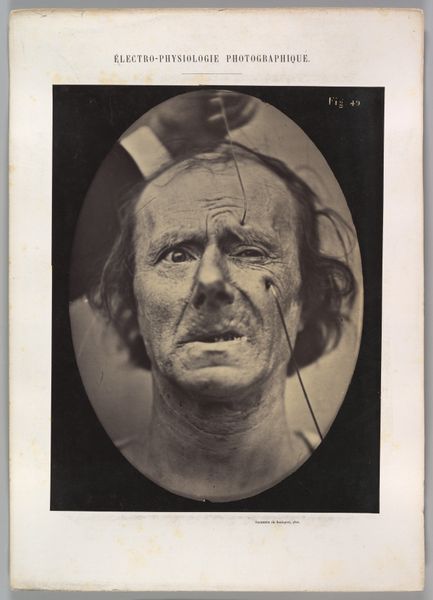

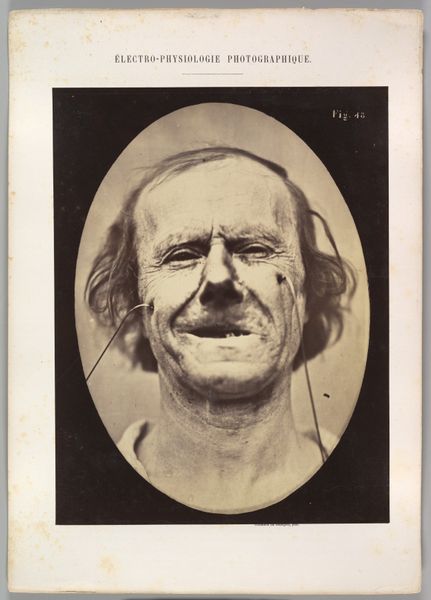

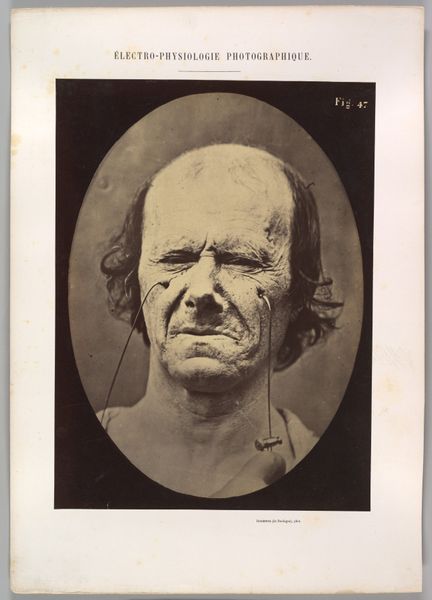

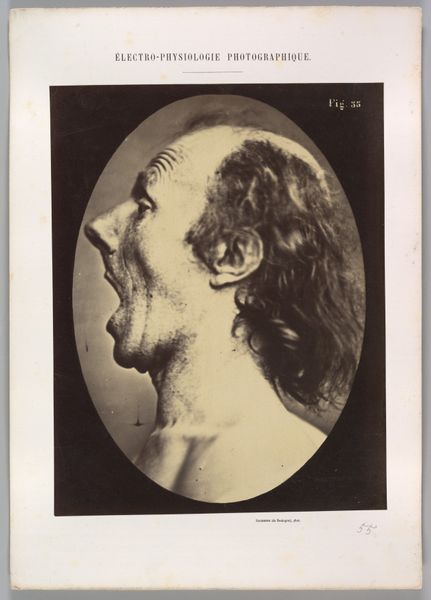

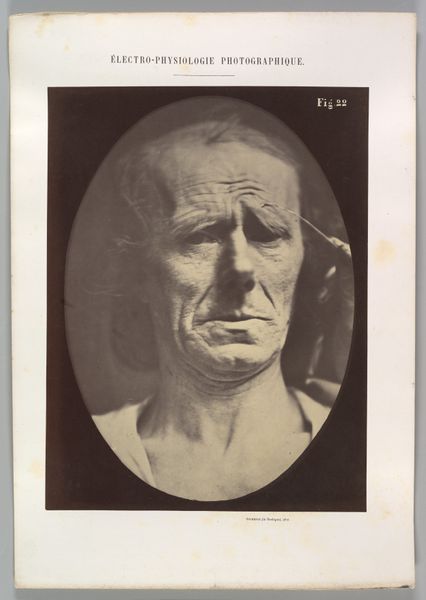

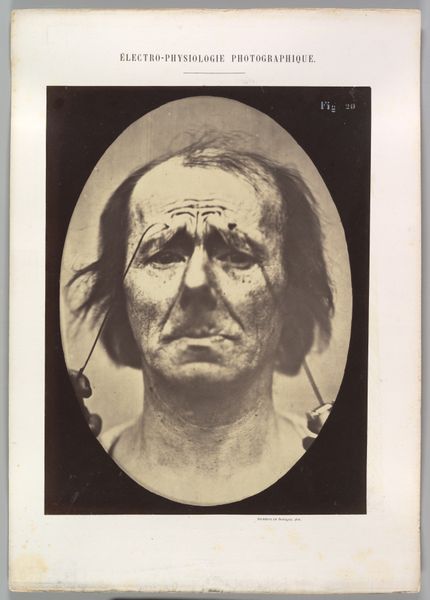

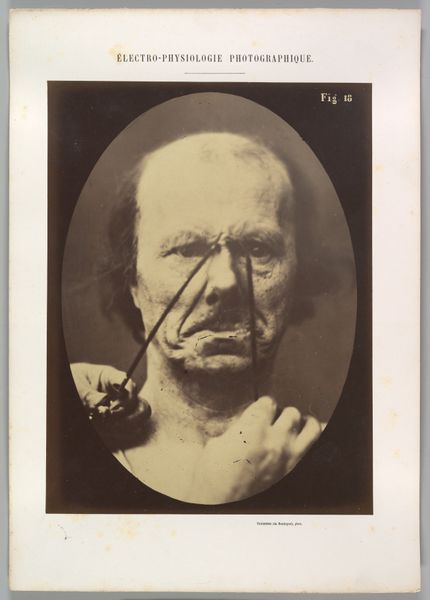

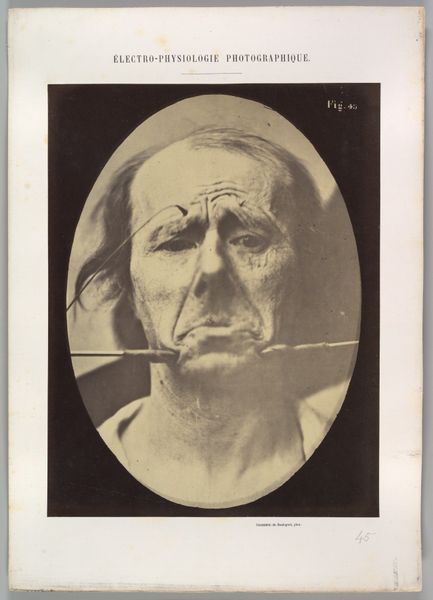

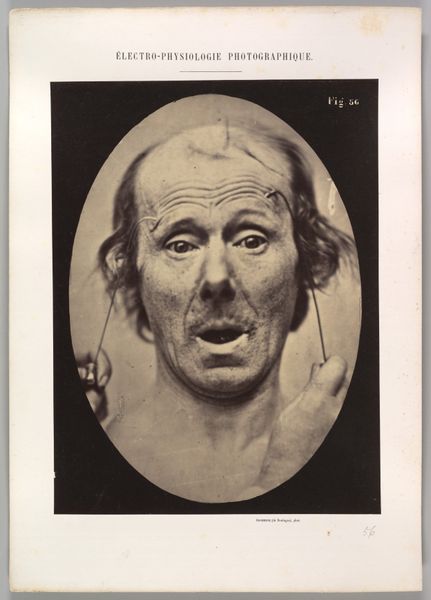

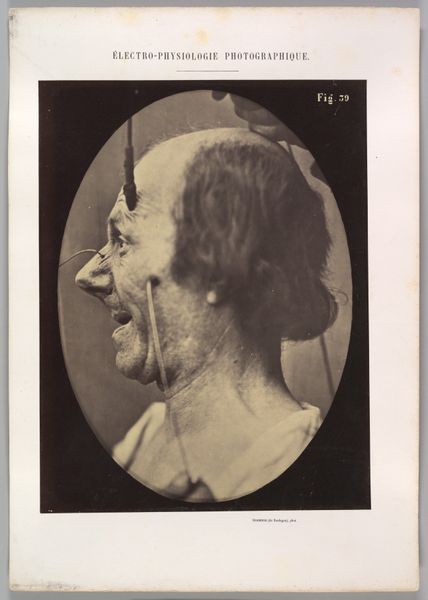

Figure 9: A study of m. frontalis in maximum contraction 1854 - 1856

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

academic-art

Dimensions: Image (Oval): 28.4 × 20.3 cm (11 3/16 × 8 in.) Sheet: 29.6 × 22.1 cm (11 5/8 × 8 11/16 in.) Mount: 40.2 × 28.2 cm (15 13/16 × 11 1/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is "Figure 9: A study of m. frontalis in maximum contraction," a daguerreotype by Guillaume Benjamin Amand Duchenne, dating from between 1854 and 1856. The image quality makes it feel… almost haunting, and quite clinical. What strikes you most about this piece? Curator: What I find compelling is the way this work exists at the intersection of science, art, and social power. Duchenne sought to codify emotional expression through scientific experimentation, essentially trying to reduce complex human experiences to isolated muscle contractions. Editor: So, it's less about portraiture and more about… control? Curator: Exactly. Think about the historical context: the rise of scientific positivism, the objectification of bodies, and the medical gaze. Who had the power to define and categorize emotions, and whose bodies were subjected to this scrutiny? We need to consider how Duchenne's work reflects and reinforces existing power structures of his time. Consider the model's own agency – or lack thereof – in this project. How might class, gender, or perceived "deviance" have played a role in his selection as a subject? Editor: It does make you wonder about the ethics behind this. Was there informed consent? Was he compensated? The image starts to feel less objective and more like a document of a power imbalance. Curator: Precisely! This daguerreotype serves as a reminder that art and science are never neutral; they are always embedded within specific social and political landscapes. How does this understanding shift your initial perception of the work? Editor: It really does. It's unsettling, but in a way that encourages deeper questioning, particularly around representation and the use of the human body. Curator: That's the power of art, isn't it? To make us question everything we think we know.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.