Dimensions: height 106 mm, width 67 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

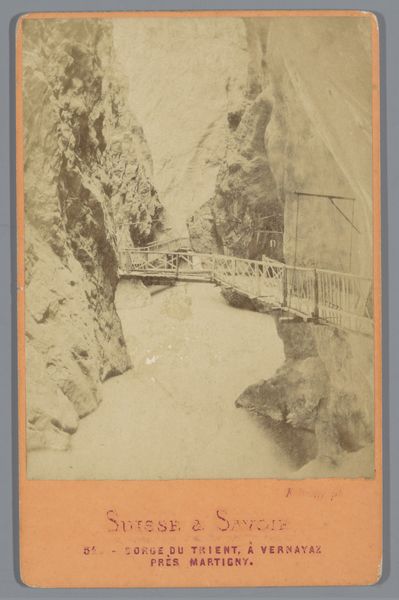

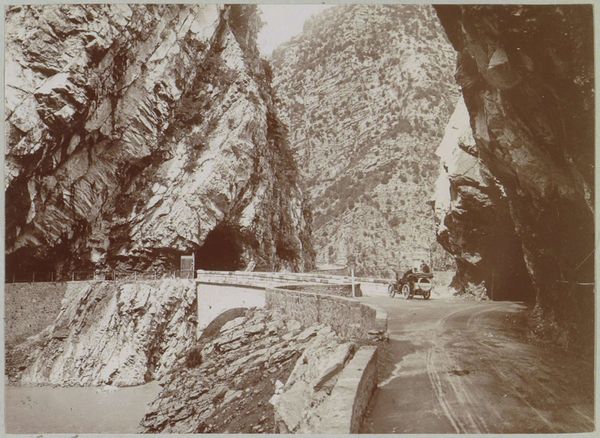

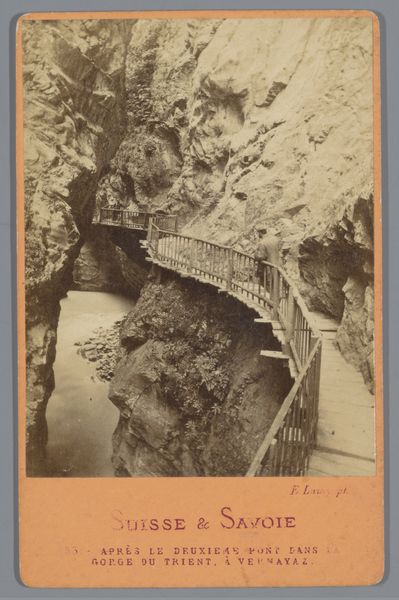

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, created in 1868, captures the Trientkloof near Martigny, Switzerland. The photographer, Ernest Eléonor Pierre Lamy, presents a rather stark, almost imposing scene. What strikes you first about it? Editor: The scale, definitely the scale. The sheer rock faces towering over those tiny figures. It speaks to a certain romantic ideal of nature’s sublime power, but with a tinge of…discomfort, maybe? Curator: It is romantic, decidedly so, fitting into the artistic and literary movement that emphasized emotion, individualism, and the grandeur of nature, after all, Switzerland became an attractive touristic landscape at that time. And yes, there's an implied power dynamic here. Look at how the photographer uses light and shadow to emphasize the verticality of the gorge, almost dwarfing the people present in the foreground. Editor: Those figures seem staged though, right? A conscious inclusion for scale, but also to legitimize this conquering gaze? Tourism’s influence made visible, like planting a flag on nature's landscape. Curator: Precisely! Their presence highlights the shift towards experiencing nature as spectacle, a view carefully curated and commodified. We should consider the print's place within the wider culture of the Swiss landscape as promoted at the time: Think of hotel advertising, guidebooks, other photographic formats available, all contributing to how and why people flocked to Switzerland, with their romantic or conquering aspirations. Editor: Absolutely. Even the tonal range – the muted sepia – evokes a sense of nostalgia, but also detachment. We are looking at a captured moment, frozen in time, making the dramatic setting both accessible and remote. It begs questions about man’s interaction with an overwhelming natural landscape in an era marked by scientific exploration and touristic curiosity. Curator: Indeed. Lamy offers us not just a representation of a geological site, but an early example of landscape photography participating in larger conversations around the cultural construction of nature. This piece becomes particularly compelling when viewed alongside other artistic mediums of that era as we’ve noted. Editor: I agree. The symbolism of these dominating rocks persists—reminders of an often intimidating world as the old one wanes. I found new perspectives and emotions with that knowledge.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.