photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

mountain

Dimensions: height 55 mm, width 89 mm

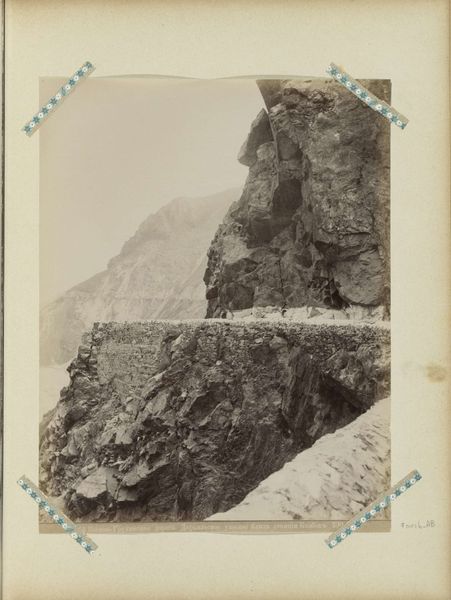

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

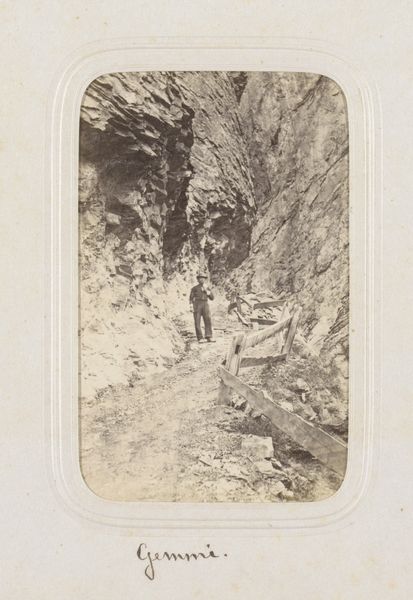

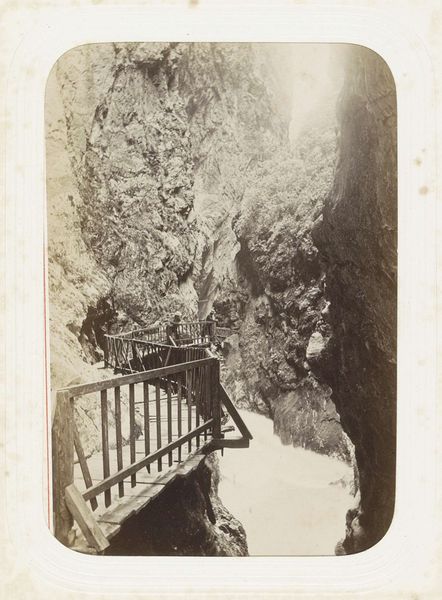

Curator: What a gripping sense of solitude I get from this photograph. The tiny figure of the wanderer just emphasizes the mountain’s immense scale. Editor: Indeed. This piece, titled “Wandelaar op een pad op de berg Gemmi in het Wallis” or “Wanderer on a path on the Gemmi mountain in Wallis," comes to us from Florentin Charnaux, circa 1871. Its restrained composition and subtle tonal gradations construct a landscape where the human presence is nearly absorbed into the formidable environment. Curator: The texture is striking! You can almost feel the rough stone, smell the crisp mountain air. It captures that solitary, meditative feeling that comes from confronting a powerful natural landscape. Editor: Look closely at the careful construction of space, that precise arrangement of forms within the photographic frame. See how Charnaux uses the path itself—that linear element receding into the distance—to draw us into the composition. The mountain wall forms a solid, imposing mass, while the distant valley opens to boundless possibility. Curator: It almost feels… theatrical. The way the light catches the edge of that mountain face, the shadowed figure in the middle distance... like a character pausing mid-scene. Editor: Certainly, a theatrical reading holds. The photographic medium flattens space, collapsing planes. That wooden handrail, for example—its geometrical clarity becomes more pronounced through this flattening, foregrounding issues of representation and artificiality. The relationship between that figure—diminutive, anonymous—and the geological immensity operates as a study of scale itself. Curator: He really seems to shrink into the surroundings, to dissolve into it... a visual representation of insignificance. Almost unsettling. Editor: I perceive not insignificance but placement. His placement gives scale to a sublime landscape of grand, architectonic form, which we access here through technical exactitude. This work serves as an astute comment on how the nineteenth-century eye, equipped with scientific tools and artistic ideals, interpreted the natural world. Curator: Yes... interpreted. Perhaps that's the source of its strange, unsettling beauty. We aren't simply seeing a mountain; we are seeing someone's idea of a mountain. A thought made visible. Editor: Precisely, and that distinction encourages a closer analysis, of this photograph as a constructed arrangement—a complex articulation of nineteenth-century values made manifest.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.