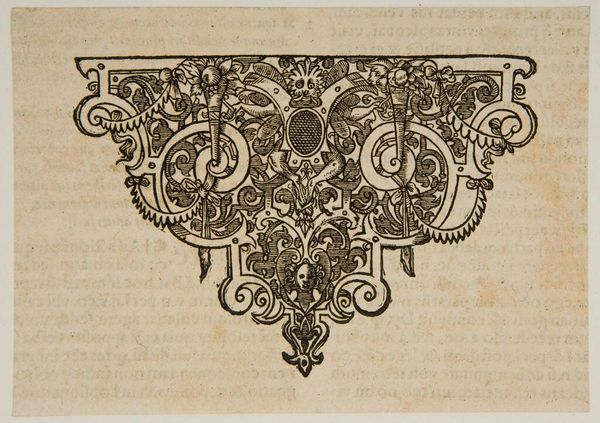

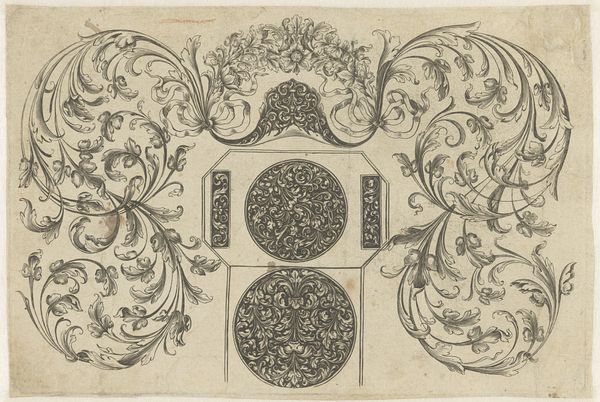

print, engraving

# print

#

pen sketch

#

geometric

#

line

#

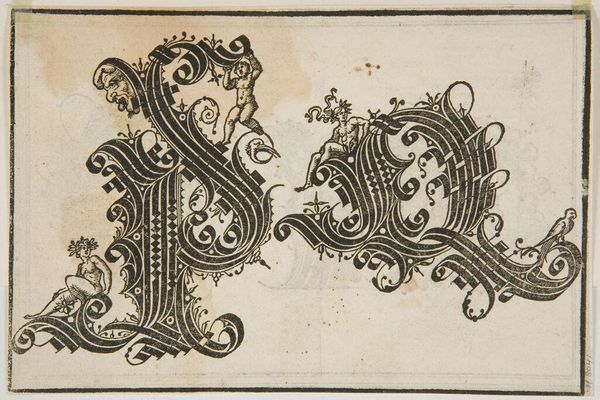

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 56 mm, width 151 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

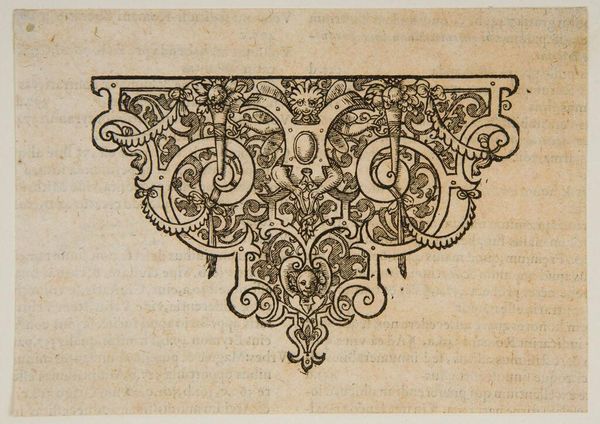

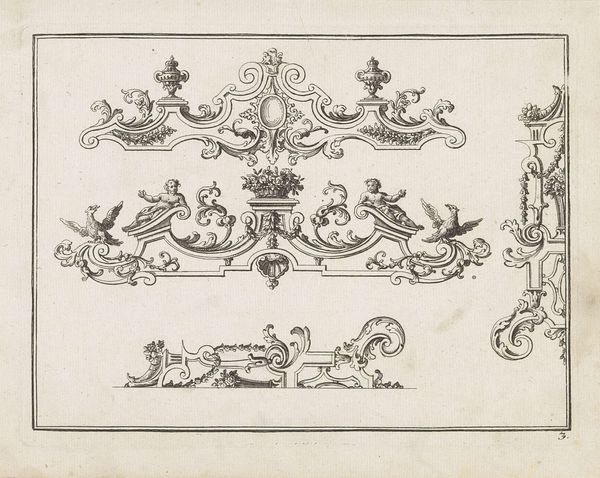

Curator: I find this piece utterly charming. "Langwerpige hoekcartouche met schaalstok," or "Oblong Corner Cartouche with Scale Bar," dates back to 1584. The artist is unknown, adding another layer of intrigue, and it's a beautiful example of engraving on laid paper. The clean lines and meticulous detail showcase remarkable skill. Editor: Immediately, my attention goes to the printmaking process itself. The tangible quality, the way the ink sits on the paper; the lines are deeply satisfying and speak to the handcraft involved, the labor intensive nature of engraving at the time. Curator: Precisely. Beyond the artistry, the inclusion of a scale bar reveals so much about the expanding worldview of the 16th century. It speaks to navigation, cartography, exploration… the ways in which Europeans were beginning to understand, and indeed, exert control over the world. We can consider how this burgeoning scientific approach also reshaped the way they viewed identity, class and, by extension, power. Editor: And that control was enacted through materials – copper, ink, paper, these elements, along with skilled labour, were fundamental for distributing knowledge and, yes, facilitating dominance. That cartouche is not just decoration; it is also part of the mapping enterprise that was occurring during the era. Its decoration hints at an underlying ambition of those producing maps. Curator: I agree. The cartouche is loaded with symbolism; even the floral motifs and the stylized mask-like forms contribute to a narrative. One could look into the symbolism of such embellishments in terms of the cultural values of the period, maybe suggesting that these were not just representations but active participants in shaping public perception and reinforcing a worldview that placed Europe at the center. Editor: Absolutely. This isn't just an aesthetic object. It represents the infrastructure of knowledge production. Consider the material impact – the consumption of resources and the exploitation of labor required for such intricate engravings. It embodies the material foundations of its historical context. Curator: It leaves you contemplating the convergence of art, science, and societal structures in the late 16th century, right? It serves as a lens through which we can understand how power and identity were actively being negotiated. Editor: Indeed, considering its physical existence reveals its historical agency. It allows us to think about art beyond pure aesthetics, pushing us to question how art creates reality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.