photography

#

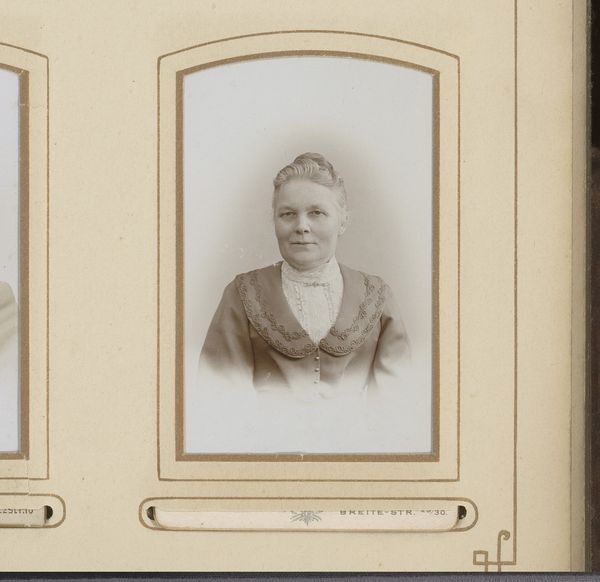

portrait

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a piece from the Rijksmuseum: “Portret van een vrouw met muts,” or, “Portrait of a Woman with a Bonnet,” believed to have been taken sometime between 1861 and 1874 by Albert Greiner. Editor: It has an incredibly still, almost haunting quality. The sepia tones and her serious expression evoke a sense of solemnity and quiet dignity. Curator: Absolutely. And the photographic process at this time involved significant labor, from preparing the glass plates to carefully controlling the exposure and developing process. It's important to consider this photograph not simply as an aesthetic object, but also the labor-intensive materiality inherent to its making and how the increasing accessibility of photography impacted portraiture's purpose in representing societal hierarchy. Editor: I'm immediately drawn to her gaze. She confronts the viewer directly, which in the context of the mid-19th century, begs the question: Who was this woman, and what were her experiences? Portraits of women from this era were often idealizations, reinforcing social norms. But what happens when we read against the grain and seek to excavate an ordinary woman’s history from the limitations placed on representing diverse identities? Curator: The way her dark dress contrasts with her ornate lace bonnet speaks volumes too. The textile industry played a massive role during that period; the starkness juxtaposed with finery perhaps offers insight to divisions of labour inherent in a time of dramatic social shift. Editor: Yes, thinking about those societal conditions makes me see resistance in her stern composure. Photography gave a voice, however constrained, to individuals who may have been excluded from mainstream historical narratives. This image becomes a potent site for reflecting on representation, agency, and the complex dynamics of identity during that period. I wonder, for example, what the bonnet signified about her religious or social affiliations? Curator: Exactly. Considering that photographic paper was also developing during the 1860s and ‘70s—not yet mass produced—each print becomes an individual record, an almost artisanal product in itself, laden with intent from start to finish. This helps humanise production beyond pure technological feat. Editor: Her image urges us to recognize and contemplate the stories of individuals historically underrepresented. Despite being seemingly conventional for its time, it encourages viewers to examine gendered societal structures in this era. Curator: It truly gives insight, then, on the relationship between art production, labor, and social identity, particularly as reflected through the technology available at the time. Editor: An invitation, indeed, to rethink traditional portraits beyond simple aesthetics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.