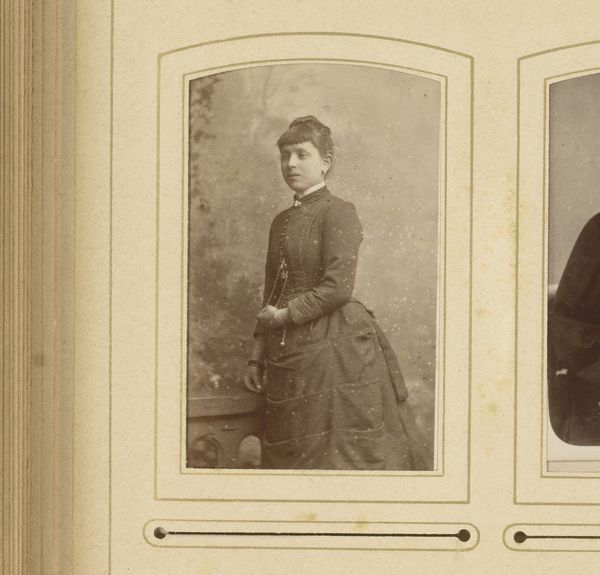

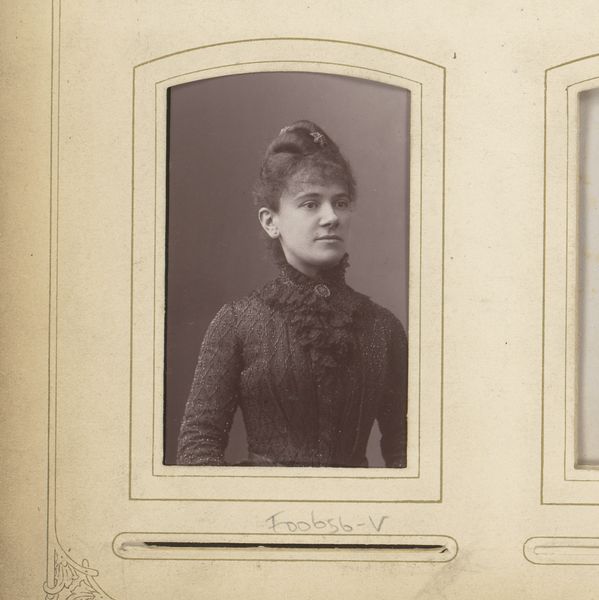

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

toned paper

#

charcoal drawing

#

charcoal art

#

photography

#

underpainting

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

#

charcoal

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This captivating gelatin-silver print, titled "Portret van een meisje," dating between 1880 and 1920, by R. & J. Fourteau Grimoneau, is truly striking. Editor: My immediate reaction is that it has a beautifully subdued quality. The tones feel very deliberate, carefully considered. It's not a grab for attention, but a quiet study of an individual. Curator: Indeed, the toned paper amplifies the sense of stillness. This was taken during a period where the very act of being photographed, particularly for a young woman, held complex social implications related to femininity and visibility. How do you interpret the materials and processes in relation to that context? Editor: Well, given it’s a gelatin-silver print, which was a popular process during this period, we have to consider its mass production context, it enabled broader access to portraiture, even if posed and somewhat formalized. Curator: That mass availability is precisely what complicates the reading of an image like this! On one hand, a portrait offers agency, but what degree of genuine self-representation was afforded to this girl? Was she able to decide how she looked? Was it something readily accessible to working-class families? Editor: Precisely, we should consider what went into producing this. From sourcing materials for the print itself to operating the equipment and the darkroom, labor is embedded within it. The act of printing, the choice of paper, even the mount—all of these involve work and a physical relationship with materials that deserve our attention. Curator: The girl’s reserved gaze feels key. In that gaze, do we read constraint, resignation, or perhaps a subtle hint of defiance within the expected norms? This kind of genre-painting, especially portraits, offers a glimpse into lives often overlooked. The social commentary emerges precisely because of the photograph’s seeming simplicity. Editor: I think it also comes down to what it does, the surface of the photograph and how it affects what it’s made of; the chemical process transformed raw materials. We can contemplate not just its subjects, but also its status as a commodity. Curator: Understanding it as a commodity reframes how we approach these images. Rather than seeking an essence of the subject, we trace the conditions of its making and circulation, revealing wider power structures at play. It's so much more than just a charming portrait. Editor: Absolutely. It highlights how even seemingly simple images can be products of complicated physical and social production systems. I'll definitely look at portraiture in albums differently after this conversation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.