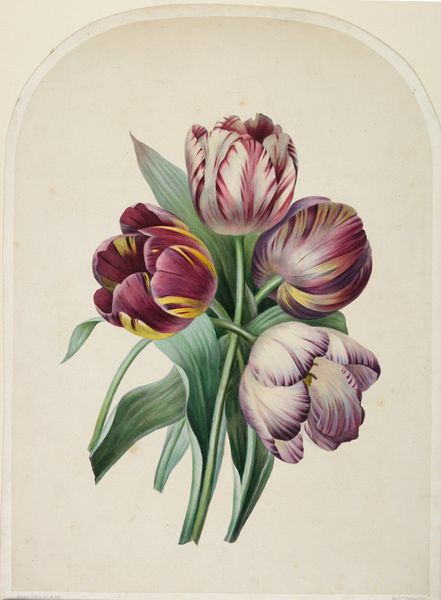

Dimensions: 19 3/4 x 12 3/4 in. (50.17 x 32.39 cm) (sheet, margins cut)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have an exquisite "Bouquet of Tulip," a watercolor print created in 1805. The artist is listed as anonymous, and it's part of the collection at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The flowers seem so delicately rendered; it's making me consider the role of detailed botanical illustrations in early scientific pursuits. What jumps out at you when you see this? Curator: Immediately, I'm drawn to the intersection of "high" art and what would typically be considered a more functional or craft-based practice. Think about the labor involved: cultivating these tulips, then meticulously rendering them through watercolor and printmaking techniques. This wasn't merely aesthetic; botanical illustrations were crucial for understanding and disseminating knowledge about the natural world. Editor: So, it was serving a specific purpose beyond just being visually appealing. I hadn’t thought about the “functional” aspect. Curator: Exactly. And it begs the question: how does the anonymous nature of the artist, likely someone working within a system of production, affect our perception of its artistic value? Was it commissioned? What role did printmaking play in the distribution of this knowledge and artistic style beyond courtly elites, thinking about material culture, and the democratization of art? Editor: It makes you think about who the audience might have been and the societal impact this image could have had at the time. Considering its function changes how we value the art and the artist. Did understanding materials shape how you now view art in general? Curator: Absolutely. It pushes us to acknowledge the full lifecycle of the artwork, from the cultivation of the plants depicted to the socio-economic context surrounding its creation and dissemination. The intersection of material culture with artmaking has always intrigued me and looking at prints makes us really see all these connections! Editor: This perspective has significantly broadened my view; now it feels more enriched. Thank you!

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

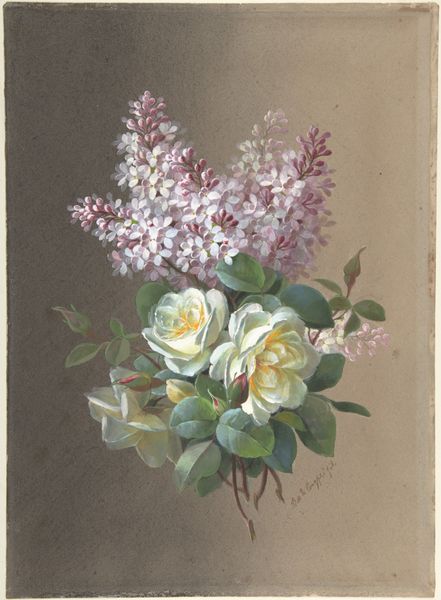

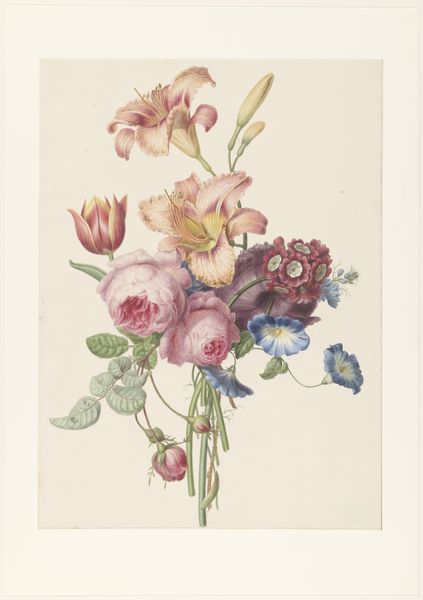

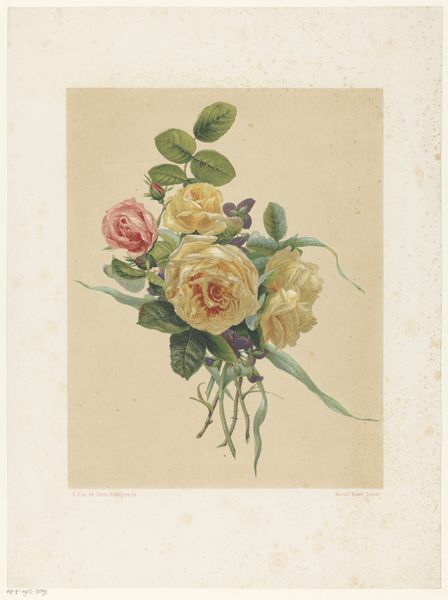

Botanical illustrators working in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries devoted themselves to the medicinal qualities of plants and sought to render plant structure and function as precisely as they could. Later, European explorers brought specimens back from exotic locales, and artists carefully reproduced them for an audience fascinated by new discoveries. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, artists had shifted their emphasis from scientific illustration to the innate beauty of the plant or flower. The Minneapolis Institute of Art is fortunate to possess an impressive collection of more than 2,000 botanical prints and drawings, among them works by Pierre-Joseph Redouté, Jean Louis Prévost, Priscilla Susan Bury, and Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.