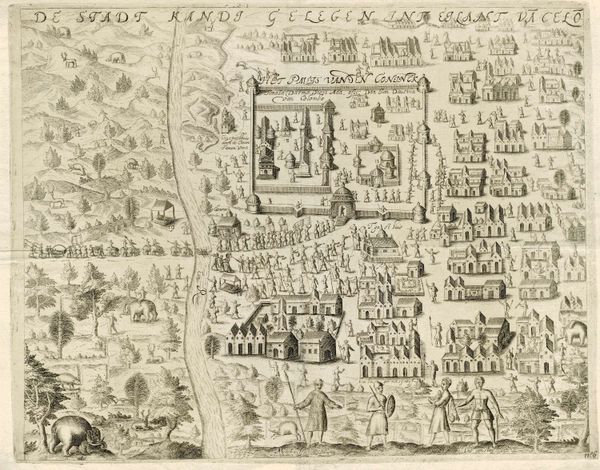

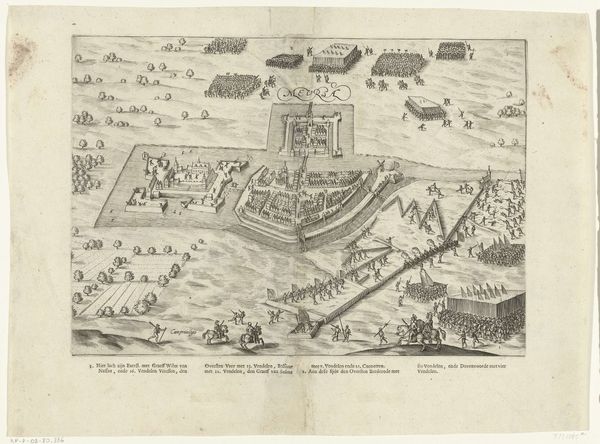

Aankomst van Van Spilbergen te Batticaloa op Ceylon, 1602 1603 - 1646

0:00

0:00

florisbalthasarszvanberckenrode

Rijksmuseum

print, etching, engraving

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

asian-art

#

old engraving style

#

geometric

#

line

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 220 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This detailed engraving is entitled "Aankomst van Van Spilbergen te Batticaloa op Ceylon, 1602," and was created sometime between 1603 and 1646 by Floris Balthasarsz van Berckenrode. It depicts the arrival of a Dutch fleet in what is now Sri Lanka. Editor: The detail is astounding! But, if I'm being honest, my first impression is of a toy town being invaded. The people look like tiny figures, almost Lego-like, amidst the architectural details. Curator: It's the perspective, isn't it? Almost bird's-eye view, like a strategic map, really emphasizing that feeling of surveying a territory. That style was fairly typical of Dutch Golden Age prints. Berckenrode captures the ambition and perhaps the clinical detachment of early colonial endeavors. Editor: Exactly! The arrival is portrayed in such an orderly way. We see the marching soldiers, and the elephants in an almost parade-like formation—a very deliberate visual of power. But how much does this sanitized image distort the actual complexities of the landing? I see the neat rows and can't help but question the lived experience. Curator: You bring up a critical point about the image as a narrative construct. Remember, this print was created to project a certain image of Dutch prowess, a show of force designed to impress viewers back home. The elephants are definitely there as exotic props reinforcing that image, even while potentially signaling other implications of the historical context. Editor: I also wonder about the absence of local perspectives here. It is as if the people are part of the architectural display. Where are their stories in this 'history painting'? What kind of negotiation, and very likely, resistance was occurring? These silences within the detailed scene speak volumes about the selective nature of historical documentation. Curator: Absolutely. And seeing it with fresh eyes makes one consider the loadedness of maps and other tools used to visualize a colonizing culture’s sense of space, conquest, and belonging. It makes this piece resonate powerfully beyond just a historical snapshot, a fascinating and sobering study on perspective. Editor: It makes one consider how such prints further cemented skewed perspectives on cultural exchange in the popular imagination back in Europe and still impacts geopolitical relations now. It makes it clear how far we need to evolve still in our own self-awareness and in how we contextualize the legacies of colonialism.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.