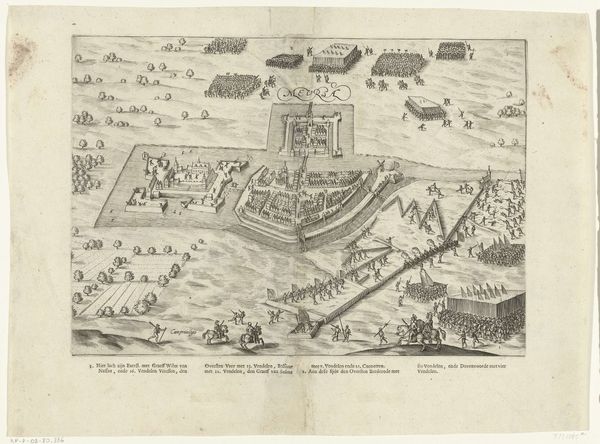

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ink

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 316 mm, width 430 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

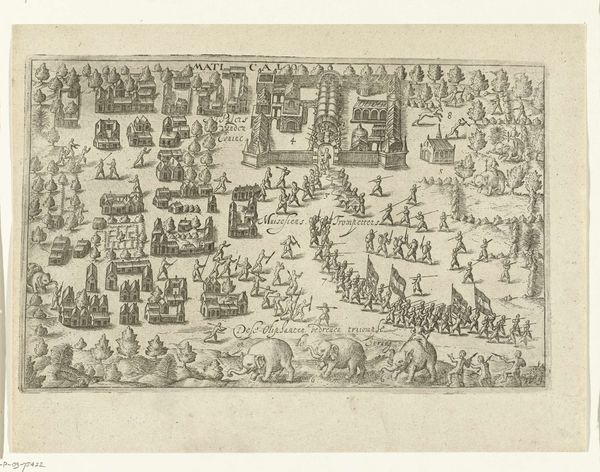

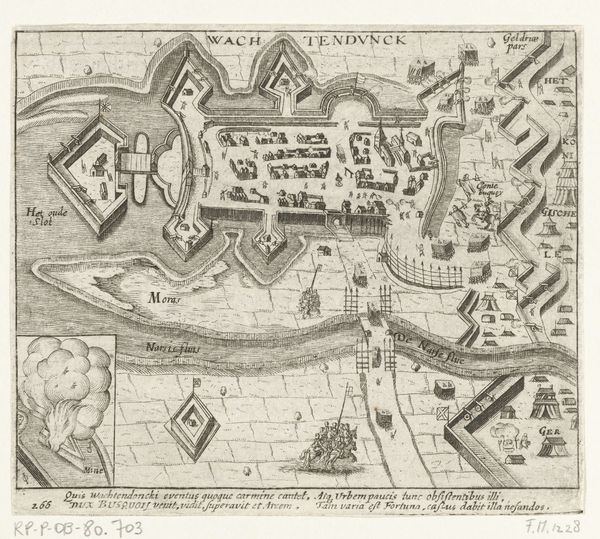

Curator: Here we have an engraving, “Aankomst van Van Spilbergen in Kandy, 1602,” made anonymously between 1644 and 1646, depicting a cityscape and landscape using pen, ink, and printmaking techniques. Editor: My first impression is one of intricacy and meticulousness. The composition is fascinating – a kind of bird's-eye view that’s almost a map, densely packed with detail, and surprisingly active given its age. Curator: Indeed. Let's consider the composition more formally. Notice the stark contrast between the meticulously rendered buildings of Kandy and the seemingly boundless landscape to the west. The rigid, geometric forms of the city clash intentionally with the wild, natural terrain. It’s a binary. Editor: And what does that binary suggest in terms of the encounter between Spilbergen and Kandy? It strikes me as representing not just a geographic place but a moment of profound cultural interaction, maybe even collision, visualized in contrasting spaces. Curator: Exactly! The visual organization supports that narrative of contrasting ideologies. Kandy, placed within walls, and appearing densely organized with people arranged in rows, versus the more dispersed landscape, implies a dialogue concerning how governance organizes space. Editor: Beyond the form, the image hints at a carefully constructed portrayal of colonial engagement. The anonymous creator subtly shapes the viewer's understanding of the event and, implicitly, of the relationship between the Dutch and the Kandyan Kingdom. Note the size difference. Curator: From a stylistic approach, this type of illustration depends on semiotics, because each constructed, though seemingly factual form becomes imbued with cultural content and value. The figures in the foreground act almost like cultural translators in between each zone. Editor: Ultimately, viewing this piece invites consideration of art’s capacity to preserve and actively construct our perception of history and to evaluate art as historical evidence but also rhetoric. Curator: In short, the interplay of form and the political and social implications of the era challenge the idea of viewing the work in purely aesthetic terms, and remind us instead that the visual space has power beyond its obvious technical construction.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.