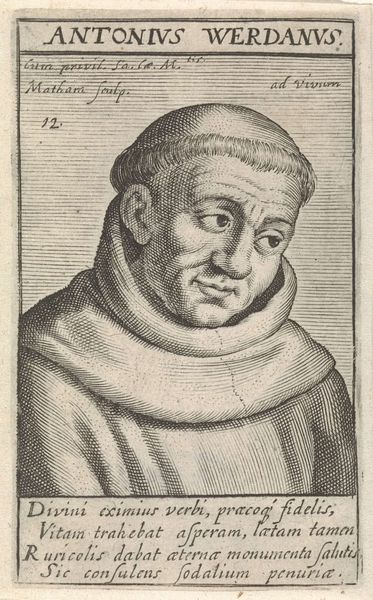

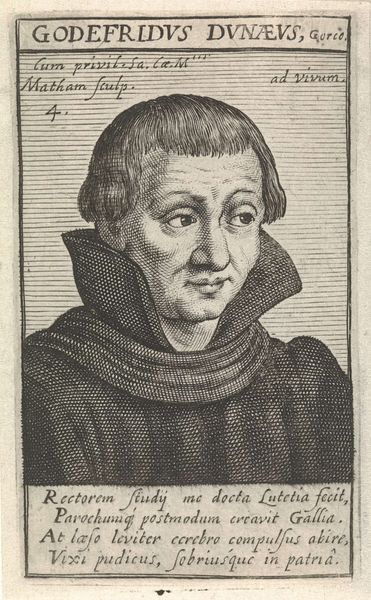

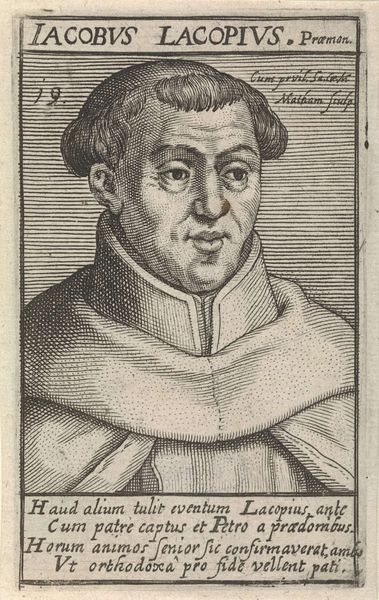

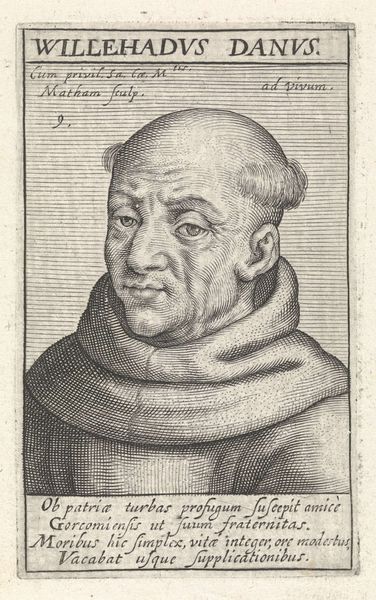

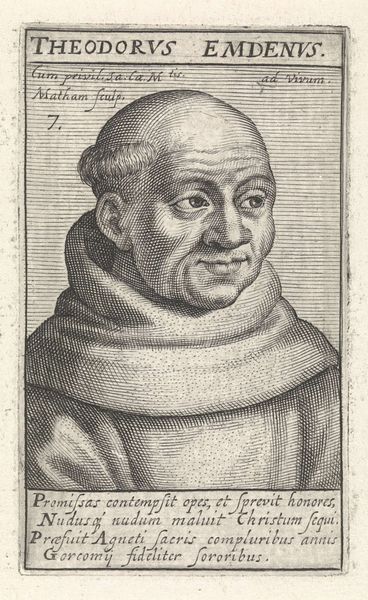

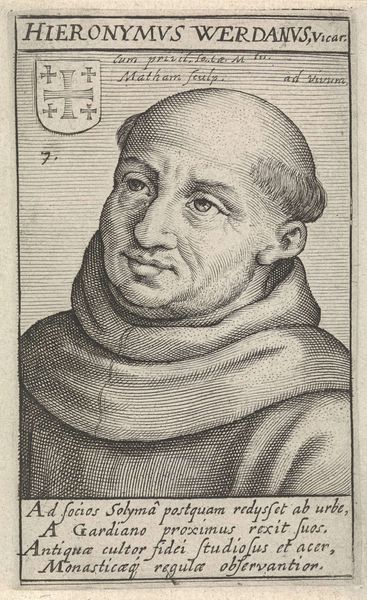

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

medieval

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 99 mm, width 59 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is a print, made sometime between 1617 and 1618, titled "Portret van H. Franciscus de Roye," created by Jacob Matham. Editor: There’s an appealing softness to the lines considering the sharp, unforgiving nature of the engraving technique. The subject’s eyes, though… there’s an almost melancholic resignation there. Curator: Well, Matham created this during the Dutch Golden Age, but look closer—Roye was part of a religious order in Brussels. Consider the context. The print almost certainly circulated among fellow clergy, reinforcing communal identity during the Counter-Reformation. These images solidified religious conviction and identity in times of turbulence. Editor: True, the visual language speaks volumes. See how the folds of his robe cascade? The formal emphasis is undeniably on line and the play of light, structuring the subject with subtle grace despite its medium, like a study in chiaroscuro reduced to linear terms. The eyes remain the focal point. Curator: And how strategic, isn’t it? Roye appears almost beatific. Prints like these functioned as propaganda. Disseminating these idealized images bolstered the Church's authority by portraying its members as virtuous and devout, directly countering Protestant critiques of clerical excess and corruption. Editor: I see your point. Yet, despite this, notice the asymmetry in his features; that slight droop of the left eyelid gives him a remarkably human quality that transcends mere propagandistic intention. The tiny hatching strokes really work together, don't they? Curator: I agree—the tension between idealized representation and individual likeness makes it truly compelling as both historical artifact and art object. This wasn't just art for art's sake. It’s deeply embedded in a very specific historical matrix. Editor: An entanglement of intent, really. Well, this image reminds me that the best art, even when serving an agenda, often has the power to inadvertently reveal so much more. Curator: Indeed, we can’t look at something like this outside the currents of power which informed its creation, yet it invites subjective consideration all the same.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.