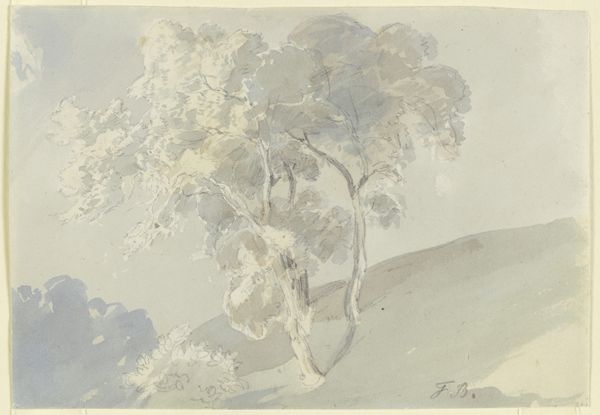

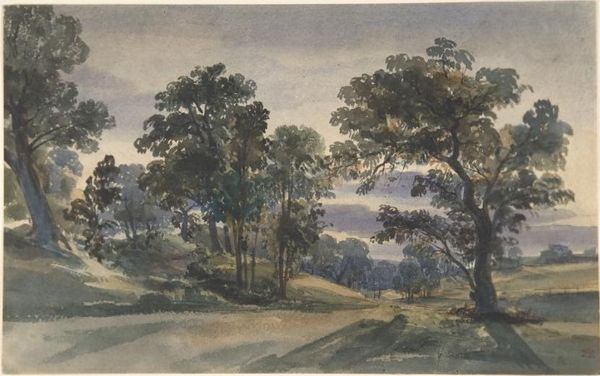

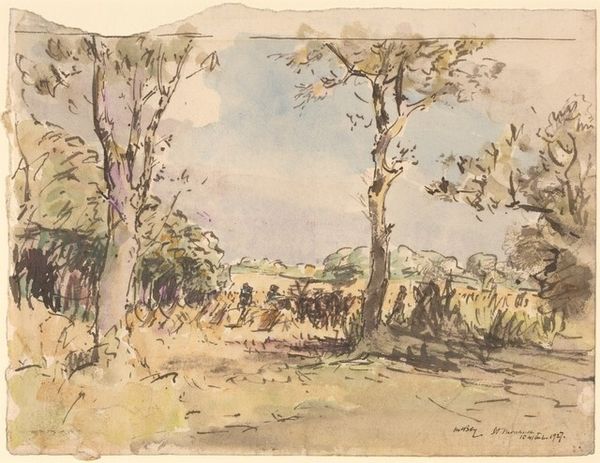

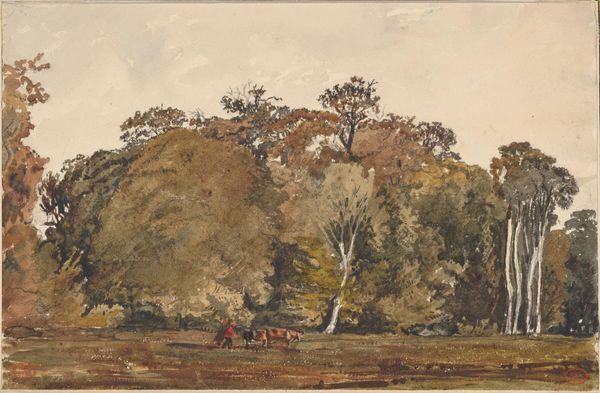

drawing, paper

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

paper

#

oil painting

#

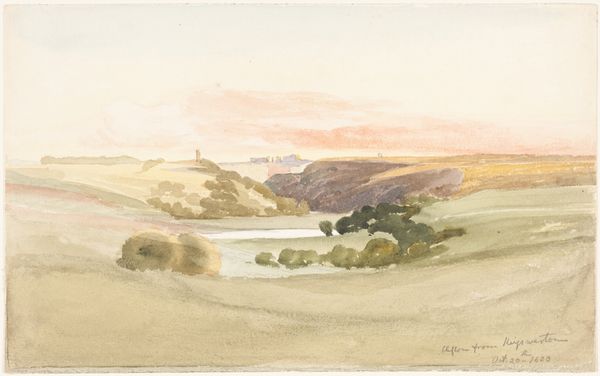

watercolour illustration

Dimensions: 5 x 13 1/4 in. (12.7 x 33.66 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

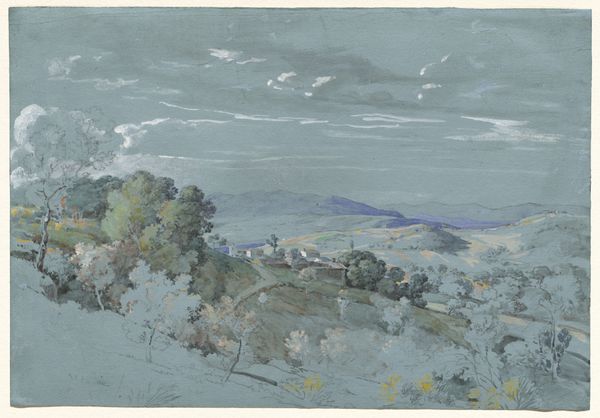

Curator: The artwork before us, titled "Montana Indian Reservation I," comes to us from the hand of Walter Shirlaw, likely around the late 19th century. It resides here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: It's ethereal, isn't it? That wide panoramic vista created with gentle washes of watercolor gives such an impression of quiet melancholy. The hues are subdued; everything fades into a sort of dreamy landscape. Curator: Indeed. The seemingly spontaneous use of plein-air—painting directly from nature—captures a moment, but what is perhaps not readily apparent are the historical layers that construct that very moment. Consider the sociopolitical context—the concept of "reservation" itself marks a history of displacement, violence, and erasure for indigenous populations. Editor: I'm curious about how the structure of the composition supports your reading. See how the hills roll gently towards the center, cradling those few figures? There's a balance between the open, almost empty foreground and the distant activities. Curator: Precisely. Those figures aren't merely pictorial elements. They are stand-ins within a broader colonial narrative—hinting at dispossession of the land, perhaps cultural fragmentation amidst assimilation pressures, and a way of life irrevocably altered by outside intervention. This perspective, viewed from afar, almost abstracts the lived realities of Indigenous peoples into aesthetic forms. Editor: Yet there is also an undeniable serenity to the land. Those strokes, so light, so soft—they do speak to a quiet understanding between the people and land they inhabit, even under duress. Is it romanticism coloring harsh reality or genuine observation through the artist’s brush? Curator: I lean toward critical interpretation. While technically skilled, Shirlaw's work cannot be extracted from the dominant worldview of his time—one often romanticizing or even exoticizing indigenous culture even while facilitating oppressive policies. His paintings served as promotion to the west for white settlers to settle what he called ‘unoccupied’ land. Editor: So the dreaminess becomes a kind of veiled ignorance then? Curator: It invites us to question our perspectives—then and now—regarding landscape art's role in legitimizing or contesting power dynamics. Editor: A stark reminder that art is never made, seen, or talked about within a vacuum.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.