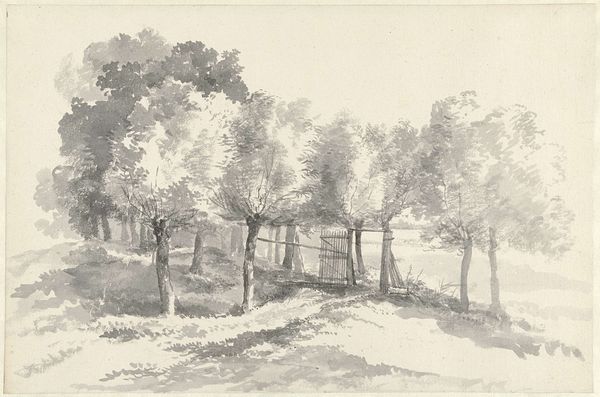

drawing, paper, watercolor

#

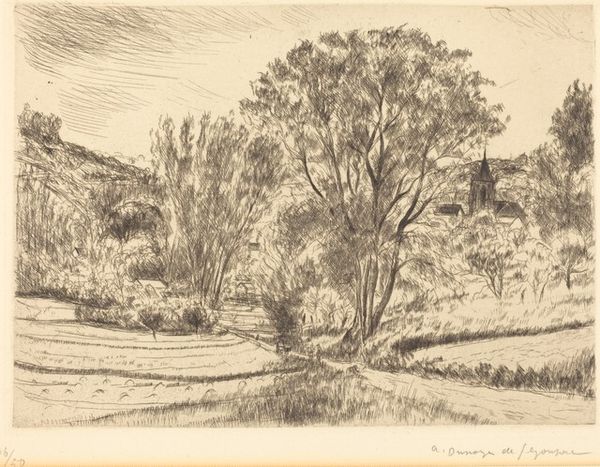

drawing

#

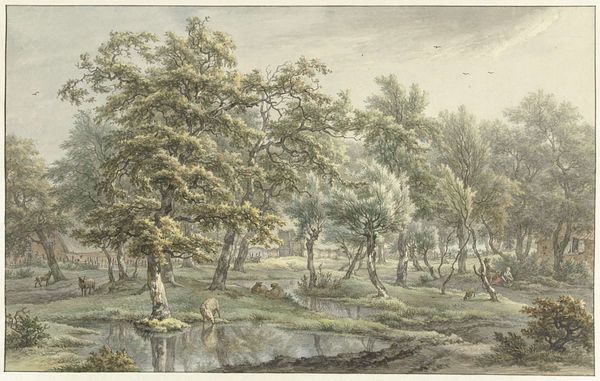

landscape

#

paper

#

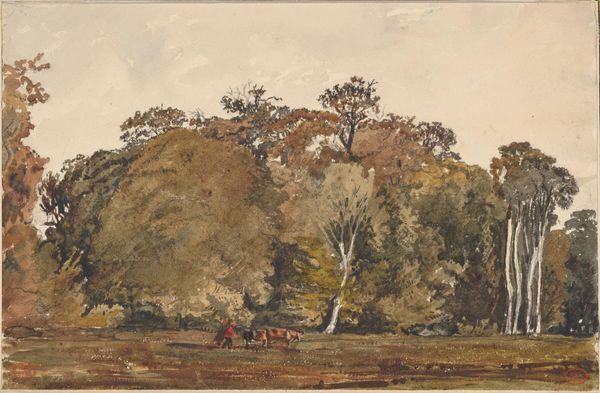

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

history-painting

#

watercolor

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

Curator: John Linnell's watercolor drawing, "Netley Abbey," created around 1810, captures a rather pensive mood, wouldn’t you say? The muted tones really evoke a sense of melancholy. Editor: Absolutely. And considering Linnell's body of work, this landscape feels almost like a document. You see the mark of the hand so directly here—the layered washes, the tentative lines describing the ruins. How does this fit into the aesthetic currents of its time? Curator: Its Romantic sensibility places great emphasis on emotional impact, contrasting the ruined man-made structure with the sublimity of the natural setting. Notice how the architectural lines, though fragmented, retain a certain geometric rigor, offset by the fluid washes suggesting a constant state of decay. The interplay between the structural and the ephemeral is really quite striking. Editor: True, but for me, the paper and the very liquid materiality of the watercolor play a critical role. Watercolour allows for accidents and serendipitous effects; I'm thinking about what its reliance on atmosphere and light signifies about Britain's increasing industrial activity and cloud cover at the turn of the century. Curator: An intriguing point. It almost suggests a symbiotic relationship, wouldn’t you agree, where industry subtly shapes the very atmosphere and therefore the visual aesthetic. This kind of landscape was fashionable because, partly, industry enabled leisure time, enabling travel to picturesque sites to paint "en plein air". Editor: Exactly. It also points to an increasing separation between those who profited from new industry and those who recorded its material traces. These rural and medieval scenes function like pastoral allegories critiquing that separation. Curator: In its deliberate composition, and execution in such ephemeral, watery medium, it creates a poignant sense of impermanence, quite profound actually. Editor: And for me, that emotional effect springs directly from the artist’s physical engagement with the material world, turning watercolor into a commentary on production, obsolescence and Britain's cultural landscape in flux. Curator: It does make you see it differently. Thank you for shedding light on the less obvious angles of this romantic depiction of a ruin. Editor: Likewise! Considering art and labour will change our perspectives and broaden our vision.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.