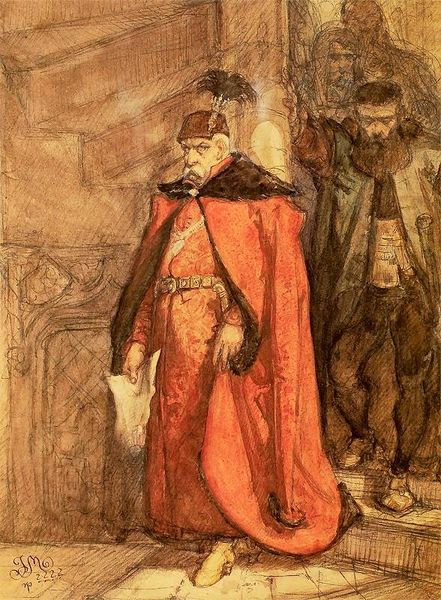

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Looking at this piece, the first thing that strikes me is its incredible texture – almost a kind of feverish, swirling energy despite the rigid formality of the subject matter. It feels raw, emotionally charged, even a little anxious. What’s your take on it? Editor: It does have an almost frantic energy, which speaks to a broader upheaval during a time when nationalism was intertwined with artistic creation. What you are viewing here is a history painting simply titled, "Coronation", created by Jan Matejko. It feels steeped in the turbulent history of Poland. Matejko was, in many ways, a nation builder using oil paint and canvas. Curator: Exactly. It's like he’s pouring the weight of history onto the canvas. The coronation itself feels secondary to the sheer…intensity. And I am also kind of moved by the king. He looks vulnerable here – almost burdened, despite the regalia and pomp. There is nothing in his face expressing pure triumph or anything else. It makes one wonder about the real weight of that crown and all that the artist imagined he was responsible for. Editor: Absolutely. It speaks to the complex relationship between power, ritual, and legitimacy. I like to question which of those factors are more powerful at that given moment. And it seems fair to critique the painting within a frame that understands power as not just something that resides within an individual but as an active field of interactions that creates new relationships and forms of marginality. I see Matejko positioning this coronation as a powerful catalyst for change, both politically and socially. Curator: Interesting… so you see him more as examining an ongoing struggle of authority and class. Editor: In many respects, yes. If we consider, for example, how the king and pope share almost equally in being at the physical centre of this historical reenactment, while others are pushed to the edge or left only half-portrayed. How might their role be subverted? What were Matejko's biases or those that came to light during his art practice? How could he challenge such traditions and disrupt our ideas of what should be deemed important enough to be depicted in paintings of significant events like the one at hand? These are questions, that can perhaps guide one to form deeper interpretations that lead into conversations of contemporary power structures. Curator: And yet, despite all that turmoil and anxiety, there's a undeniable romantic grandeur. The cross above them all, for instance. What do you think about its role? I see it almost as an element of stability. I think he intended for the cross to have much significance. What do you think of the cross' role here in our modern considerations? Editor: I interpret its function in a far more grounded framework: The Church has undeniably wielded its control on historical outcomes by aligning with state powers, like monarchs or those figures of nobility portrayed within such royal or prestigious scenes in paintings just as "Coronation". This reinforces to me that the church seeks only to solidify itself under its ever-looming power structure and to remain actively involved wherever relevant regardless whatsoever any repercussions should take hold throughout communities influenced or overseen given all which are presented within society! Curator: I hadn't considered the extent of it's weight or perceived dominance within the overall narrative. But now, that’s a viewpoint I certainly will have to sit with. Editor: The painting allows for multiple interpretations, as the function of art in many ways involves offering these alternative readings. Ultimately, how we perceive such moments of crowning tells a great deal about where we stand within our own contexts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.