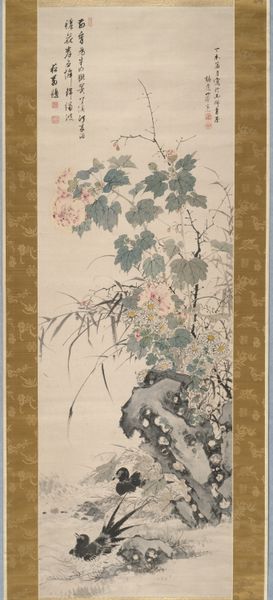

Dimensions: Image: 36 1/4 × 13 5/8 in. (92.1 × 34.6 cm) Overall with mounting: 65 1/2 × 19 3/4 in. (166.4 × 50.2 cm) Overall with knobs: 65 1/2 × 22 1/2 in. (166.4 × 57.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: So Shizan's *Flowers and Goldfish*, likely created sometime between 1733 and 1799, presents us with a delicate rendering of nature, using watercolor on what appears to be silk or paper. The work hangs here at The Met. Editor: My first thought is how light and airy it feels. The pastel colours create a serene, almost dreamlike atmosphere. It reminds me of those ukiyo-e prints, but with a distinct painterly quality, what do you think? Curator: Absolutely. Ukiyo-e, or "pictures of the floating world," were incredibly influential during the Edo period. Shizan's work engages with those themes, yet adds a personal touch. It is an expression of leisure and aesthetic appreciation, particularly from a rising merchant class finally afforded the privilege of contemplating beauty rather than constantly labouring for survival. The goldfish, in particular, have meaning; they were seen to symbolize wealth and abundance. Editor: The positioning of the goldfish bowl also interests me. Elevating these fish—quite literally—demonstrates an intimate, but unusual type of labour. Fish keeping and careful attention towards their daily living can be aligned with human productivity in contemporary Japanese life. Are there historical class or gender implications related to this kind of hobby in the late eighteenth century? Curator: Certainly. During this time, such leisurely pursuits became markers of social status, distinguishing the elite from the working class. Women in affluent households often cultivated skills like painting and flower arranging. Even goldfish keeping and breeding was viewed, especially among courtesans, as something graceful and refined. We need to recognize that, behind such representations of women in Japanese art, lay specific expectations. Editor: What strikes me is how such delicate imagery hides the socio-economic shifts. The emphasis on materiality, like imported inks and silk supports how commodities themselves take centre stage through detailed depiction. It suggests networks of material production supporting art like this. Curator: True, the artistic choices reflect broader power dynamics, gender roles, and economic changes during the Edo period. Editor: This has reminded me how art objects always exist at the intersection of material culture, gendered expectations, and historical context. It forces me to question simplistic notions of beauty in a time of complex societal changes. Curator: For me, it’s about appreciating art’s capacity to record, question, and reflect these historical layers, to tell these intertwined narratives of wealth, gender and representation in new and compelling ways.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.