print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 185 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

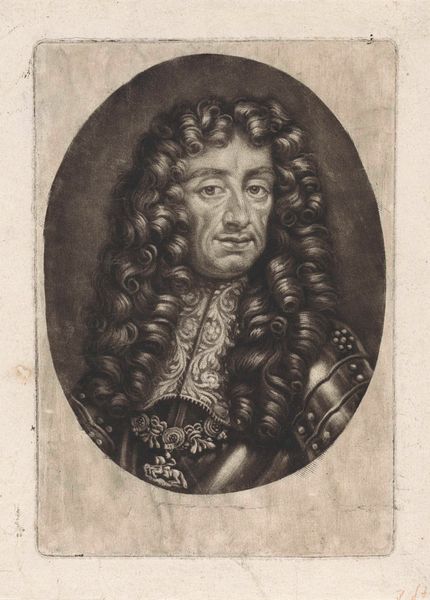

Curator: Let's have a look at "Portret van Friedrich Arnaud hertog van Schomberg," an engraving by Jacob Gole dating between 1670 and 1724. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate impression is one of strength mixed with world-weariness. The detail in the armor clashes intriguingly with the soft, almost dreamy treatment of his hair. Curator: Yes, and consider how an engraving like this would have been produced. Each line, each area of shading, meticulously carved into a copper plate. Think of the labor, the skill, the physical demand. It speaks to a specific economy of image production. Editor: And within those precisely rendered lines we see Schomberg, presented almost as a heroic figure—a portrait framed by inscription in Latin and another language perhaps Dutch? The text curls around the image reinforcing the man as both subject and symbol. I wonder how conscious Gole was of invoking the weight of classical portraiture while depicting a modern commander? Curator: The inscription absolutely plays into the construction of this portrait. Its inclusion highlights the culture surrounding image making during that period. An art for a specific consumption, laden with clear societal meanings. It really emphasizes how portraiture in print existed as a material object, not just a representation of the man, but to solidify certain sociopolitical meanings. Editor: I agree. The way he’s glancing over his shoulder—it hints at vigilance, and perhaps a touch of vulnerability beneath the layers of armor and the formidable wig. It's the look of a man burdened by his responsibilities, a powerful ruler under constant observation, whose portrait will be hung as an example or a reminder of who holds the power. The baroque ornamentation feels particularly meaningful. Curator: I think that analysis underscores an important connection between image-making, material labor, and social control during this period. Printmaking allowed such portraits, carrying all their imposed cultural importance, to circulate amongst a broad segment of the society and beyond. Editor: I find it powerful to see those symbolic associations so vividly presented—the sitter a combination of historical and psychological, rendered in the texture of the etching itself. Curator: This examination gives me new perspective to the function and construction of the artwork. Editor: And to me a greater sensitivity to the power of imagery and how visual symbols reverberate throughout culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.