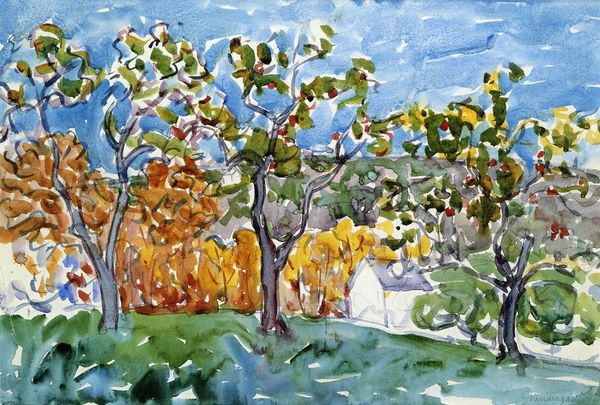

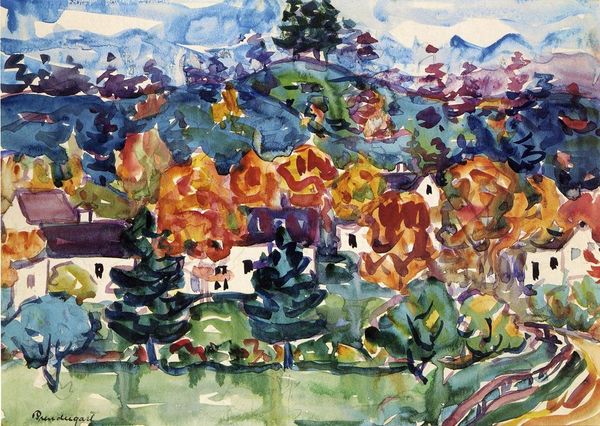

Dimensions: 50.48 x 35.24 cm

Copyright: Public domain

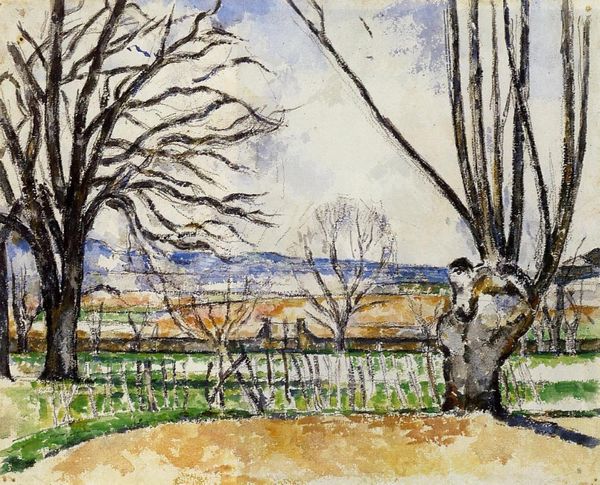

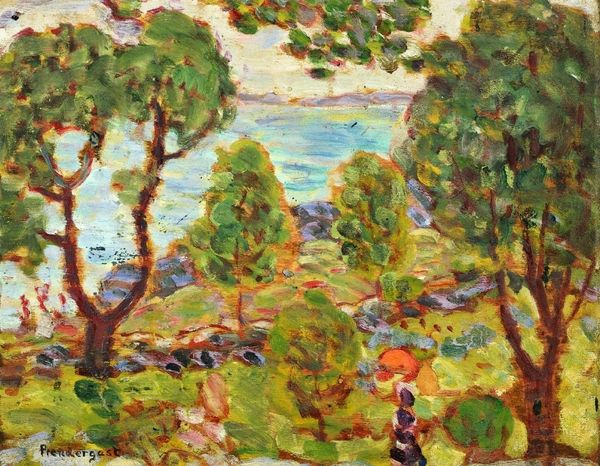

Curator: Looking at Maurice Prendergast’s “Farmhouse in New England” from 1923, currently held in a private collection, my immediate impression is of a vibrant, almost chaotic garden scene. The brushstrokes seem incredibly free. Editor: Absolutely. What strikes me is how this plein-air painting, done in watercolor, really collapses the distinction between what one might call ‘high art’ and the material reality of rural life at the time. You see, it presents the means of production, from raw pigment to artisanal technique, rather than focusing merely on representation. Curator: I think it speaks to Prendergast’s grounding in post-impressionism, a rejection of strict academic representation. Consider the houses. They’re there, but not precisely defined. They're forms in a landscape rather than architectural studies. What might that tell us about the societal view of rural architecture then? Editor: Possibly that. But think of the labor embedded within those quick strokes: the artisanal manufacture of the paper itself, the sourcing of the watercolor pigments. And, I see a specific commodification of "New England" as a landscape of leisure, ready to be consumed by an increasingly urban art market. Was he subtly complicit or critiquing the way a rural idyll was marketed? Curator: That's an intriguing perspective. One thing that interests me is the positioning of the picket fence in relation to the farmhouse itself. It subtly hints at class and ideas about privacy, even segregation, a stark reality even within idealized rural settings. It is an idealized scene, but, even for an impressionist work, how do you interpret this landscape? Is this a fantasy? Or documentation? Editor: Perhaps it's both, reflecting both the artistic license and the marketing imperatives of the time. Prendergast likely intended to portray the visual impression, but his own labor, coupled with market demand, turned New England into an easily digestible commodity for affluent buyers. Curator: It makes me wonder if we should resist purely aesthetic interpretations and delve deeper into the work's place in the history of labor and material consumption. Thank you for sharing your insights. Editor: My pleasure, these works always open rich questions when we allow the dialogue of history and matter to flow together.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.