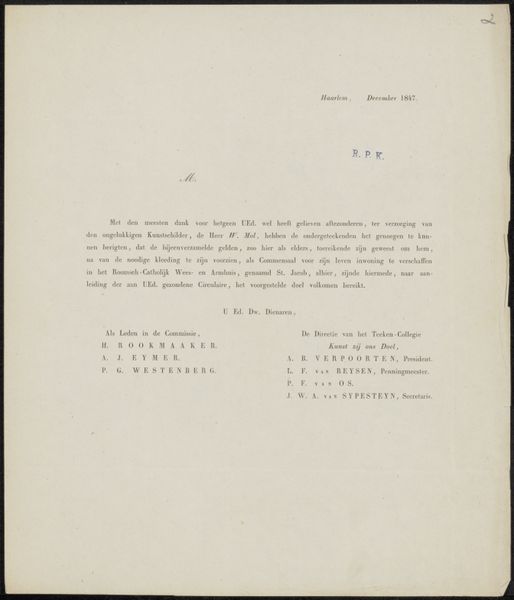

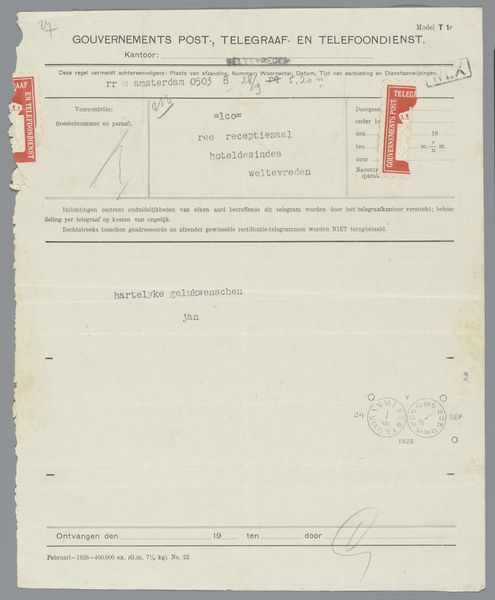

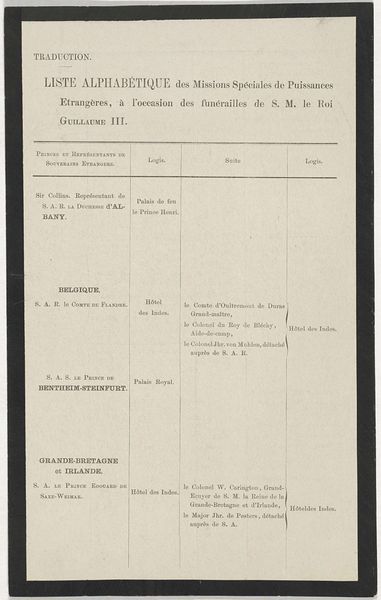

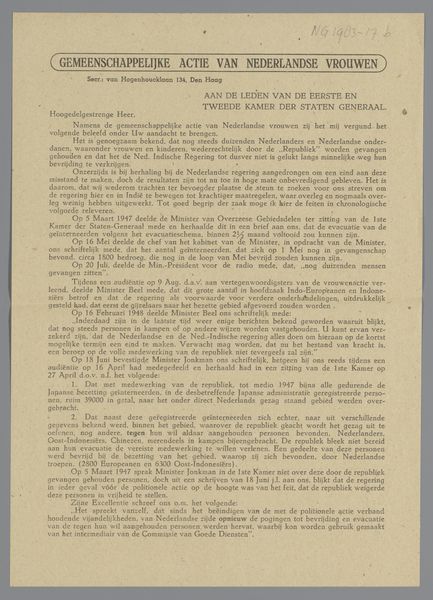

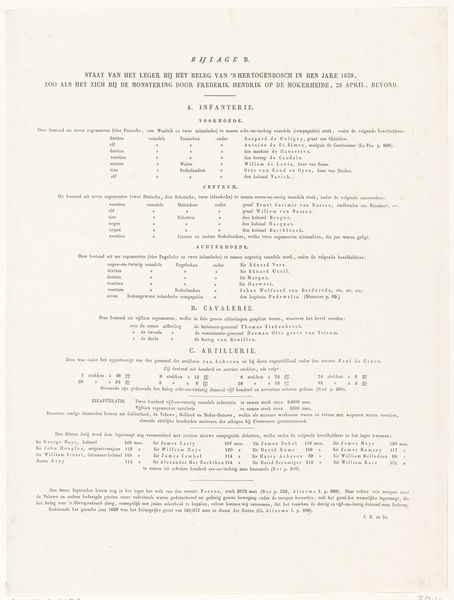

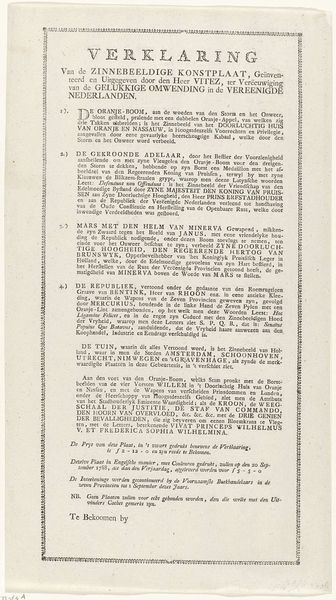

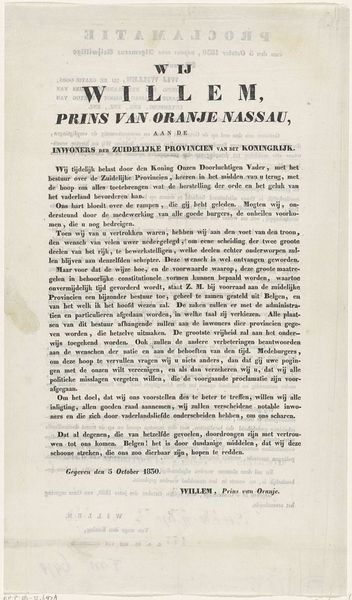

Bestellingslijst bij het portret van Frederik, prins der Nederlanden 1845 - 1846

0:00

0:00

wdegrebber

Rijksmuseum

print, typography, engraving

#

portrait

#

script typeface

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

hand drawn type

#

typography

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

fading type

#

stylized text

#

thick font

#

handwritten font

#

classical type

#

engraving

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 325 mm, width 206 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

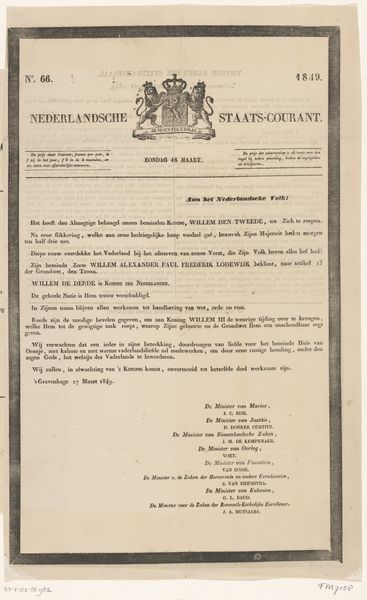

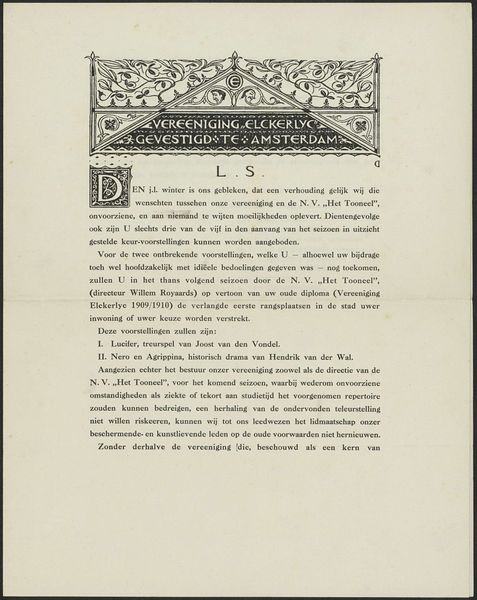

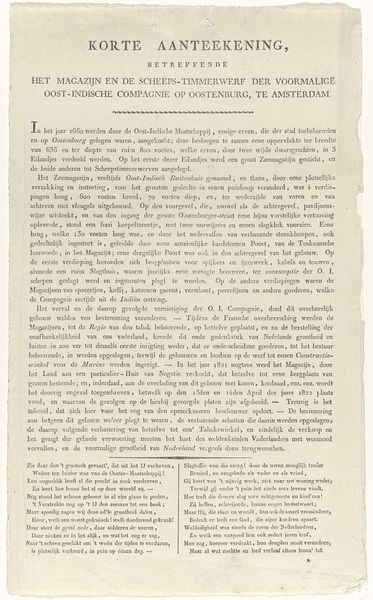

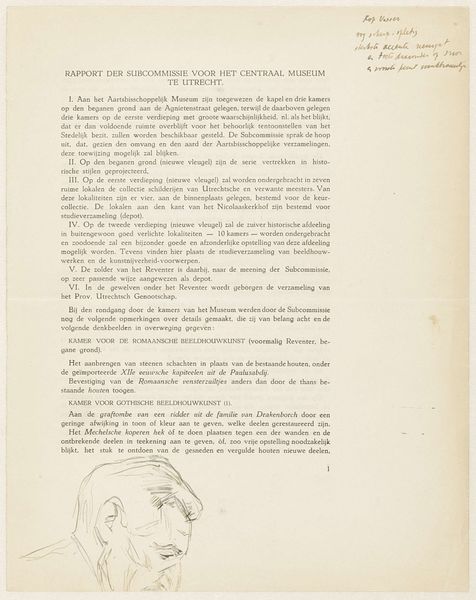

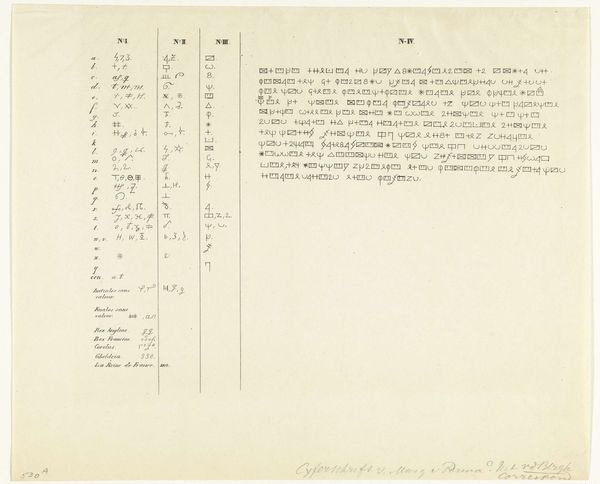

Curator: Here we have a print from between 1845 and 1846, "Bestellingslijst bij het portret van Frederik, prins der Nederlanden," housed here at the Rijksmuseum, made by W. de Grebber. It's an engraving, so we're looking at a mechanically reproduced image… what's your initial reaction to this rather functional artwork? Editor: I find it incredibly elegant, in a utilitarian way. It's like a beautiful spreadsheet from another era. The scripted typeface at the top gives it a real sense of importance, despite its humble purpose as an order form, I assume? Curator: Precisely. It's an order list for a portrait of Prince Frederick of the Netherlands, meant to be distributed in conjunction with J.P. Lange's biographical dictionary. The details matter here: it mentions the portrait will be engraved on steel, printed on "velin Jesus" paper – a specific kind of high-quality paper – and offered freely to those who order before September 15th. We're witnessing the marketing tactics of the era, the business behind art. Editor: The emphasis on materials really shines through. "Velin Jesus" paper… it almost sounds like a religious relic! Knowing that detail adds a layer of richness, highlighting the quality promised and, perhaps, a touch of aspirational luxury for the buyers. The pricing information, too, offers a tangible sense of what art was worth back then. Curator: It does! There were tiered pricing based on quality and the sheet ends up revealing a lot about the conditions of artistic production at the time. The closing date for orders, the engraver's name – W. de Grebber – it all speaks to the processes of commissioning and distribution, a web of economic relations supporting the production of art for public consumption. Editor: I agree completely. I was also struck by the formality of the typography. The careful balance between serif and script evokes the classicism of the Neoclassical period and there is something about the hand-drawn quality, even if its mechanically reproduced, it evokes trust in its readers. Curator: Yes, even the act of filling in the form becomes a part of the work's history, as customers interacted with and physically altered the object. And, beyond the single image of the prince, consider the layers of labor involved in the engraving itself, the printing, and its circulation. Editor: Thinking about how each form may have been personally delivered, the touch it evokes connects it back to both artistry and enterprise, transforming it from mere advertisement into something intimate, something personal—a document not only about value, but trust. It allows us, even centuries later, to feel like we're invited into something historic.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.