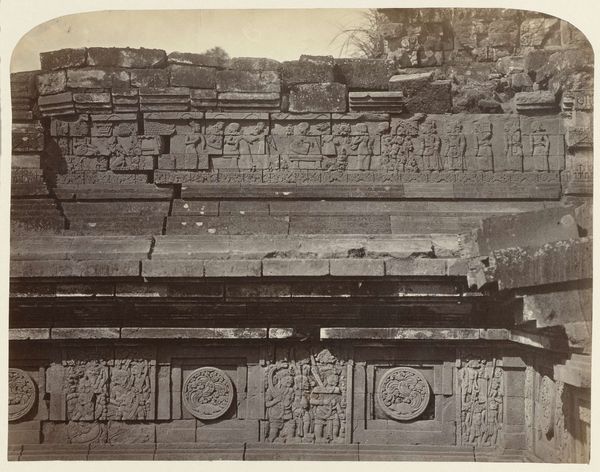

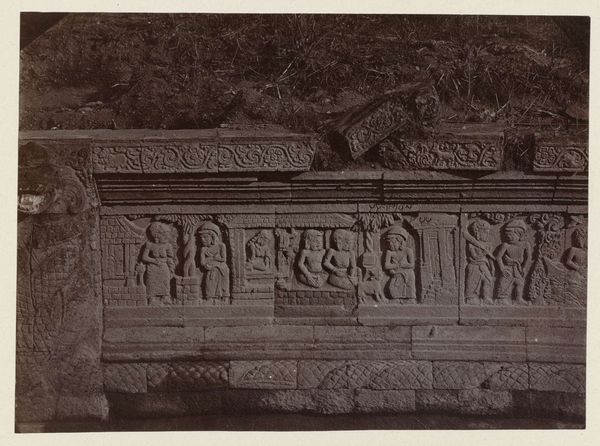

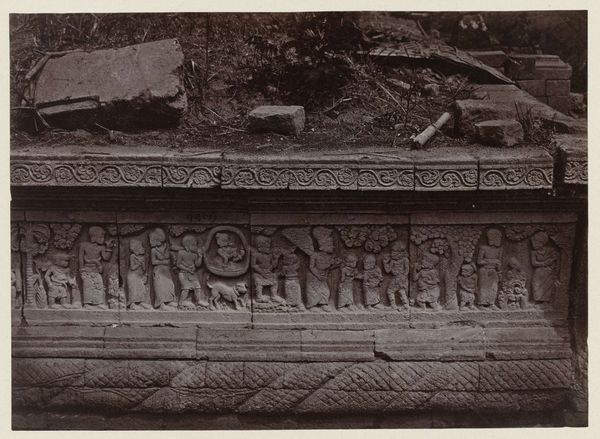

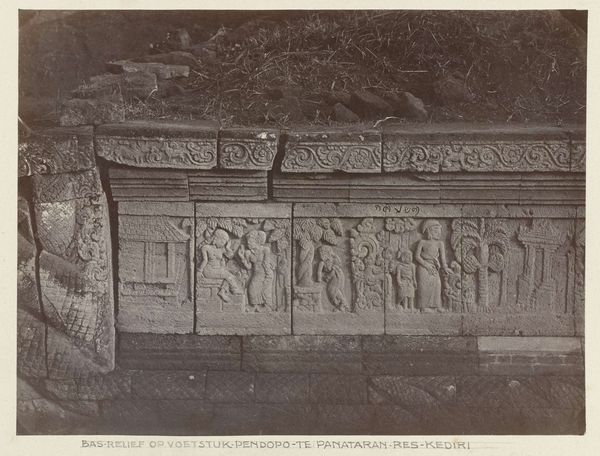

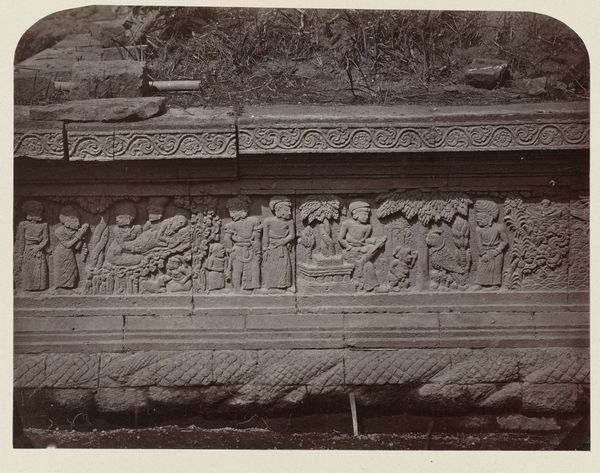

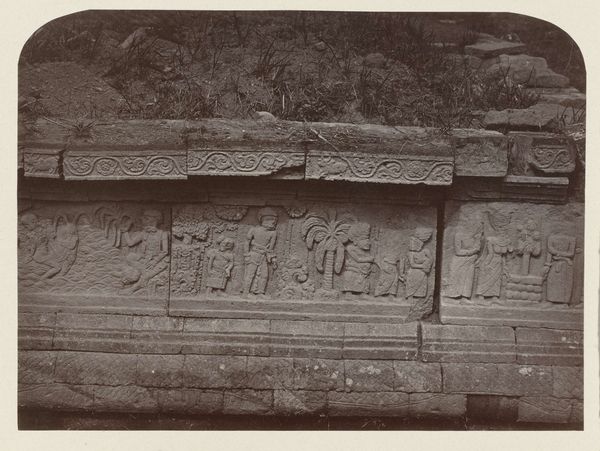

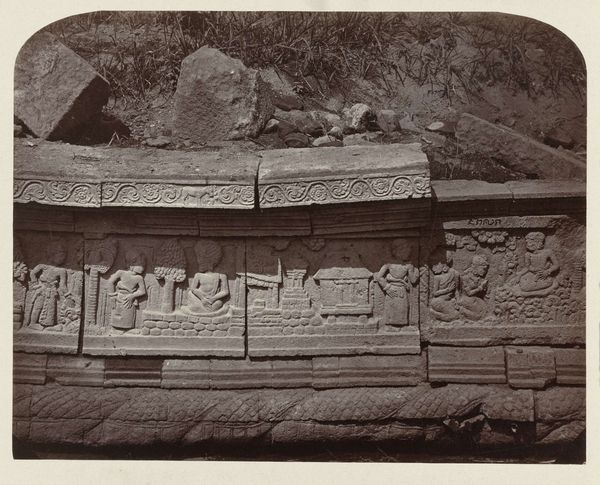

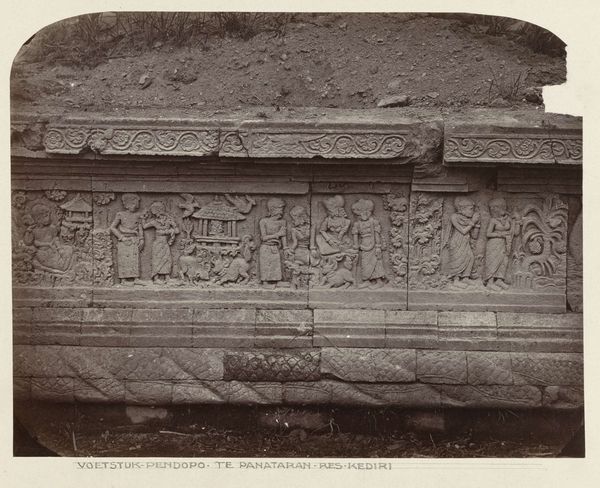

Basreliëf op het pendopo voetstuk aan de westzijde van Candi Panataran. Possibly 1867

0:00

0:00

carving, print, relief, bronze, photography

#

carving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

asian-art

#

relief

#

landscape

#

bronze

#

photography

#

carved into stone

Dimensions: height 210 mm, width 260 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me immediately is the sheer amount of detail packed into this relatively small space. It has an intense, almost overwhelming density. Editor: Precisely! Let’s contextualize. What we're observing here is a photograph by Isidore Kinsbergen, taken around 1867, showcasing a bas-relief carving on the pendopo, or pavilion, pedestal at Candi Panataran. It's narrative art rendered directly onto the stone. Curator: So, this isn’t merely decorative; it’s telling a story. And in its aged condition captured through the lens, it evokes an era brimming with sociopolitical tension in Java. Who had access? Who got represented and how? Editor: The choice to immortalize these stories in stone speaks volumes about the temple’s role in disseminating cultural and possibly political ideologies. Considering that temple art frequently served as visual texts for populations where literacy was limited, the imagery's role became one of immense cultural relevance and social influence. Curator: Looking at it, I’m wondering, how did the patrons envision the intersection between this sacred place, social hierarchies, and their own mortal existence? Are these people celebrating life or immortalizing something after their life? What did daily life look like in Java during this period? What sort of pressures did its people endure at that time? These stones whisper to our understanding of that world. Editor: I agree entirely. The level of workmanship involved also suggests the temple was either undergoing major restoration or significant modification at the time Kinsbergen documented this bas-relief. Each element represents the conscious, directed and skilled decisions. Curator: These kinds of reliefs at Panataran often served as mnemonic devices too. Looking closer—at what might appear stylized is maybe something related to performative traditions—and by interpreting these stones, can tell stories not often featured in Western colonial texts. Editor: And in documenting it via photography, Kinsbergen indirectly facilitated that story reaching entirely new audiences, albeit shaped by his own colonial context and biases. The stone-cut narratives still engage with these dynamics in complex ways for audiences who observe it today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.