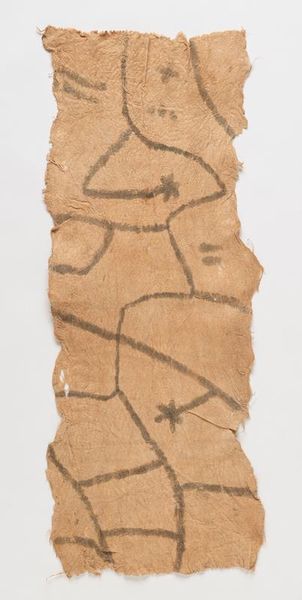

pigment, textile

#

pigment

#

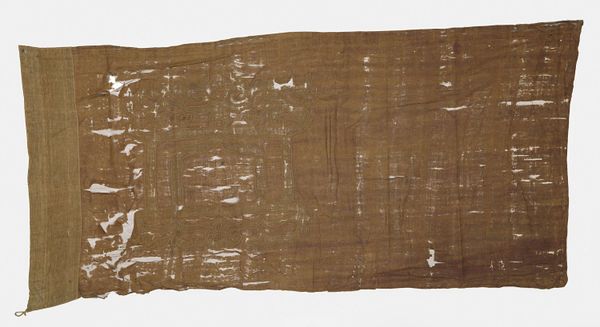

textile

#

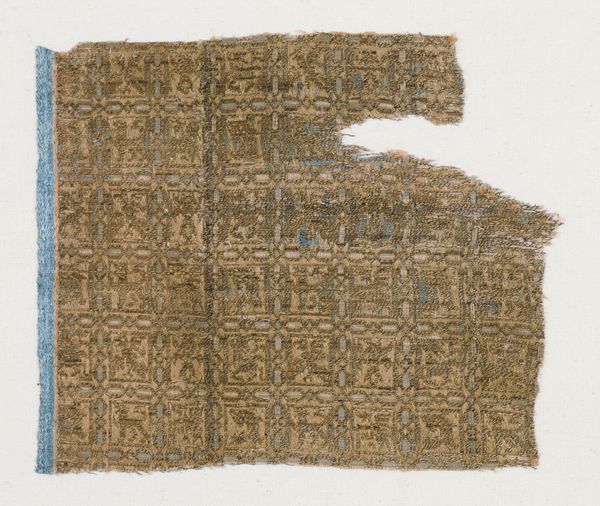

animal print

#

organic pattern

Dimensions: 32 × 23 1/2 in. (81.28 × 59.69 cm)

Copyright: No Known Copyright

Curator: Immediately, I notice its rather earthy color palette and simple, geometric shapes. It gives a raw, almost primal impression, doesn’t it? Editor: This is a barkcloth panel created around 1930 by an Mbuti artist. It's comprised of textile, pigment, and likely drawing techniques and currently held in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Curator: Barkcloth... so it's literally made from tree bark? What does that tell us about its function and production? Editor: It indicates a deep understanding and utilization of natural resources. The labor involved in harvesting and processing the bark, then decorating it with pigments, speaks to a close relationship with the environment and a certain division of labor within the Mbuti community. The final piece probably served purposes of clothing, blankets, ritual adornments, and more. Curator: Exactly. I wonder about the availability of specific materials—did that impact the artistic choices? Was this an everyday practice, or reserved for special occasions dictated by communal need and ritual? Editor: Well, Mbuti art historically had the challenging circumstance of a limited reach to external markets, so we have an enduring tradition of indigenous artistic expression. However, understanding this panel within the wider context of colonial encounters is vital, for it can also reveal ways of life impacted by trade or suppression. Consider, what narrative might the panel hold considering its status and potential meaning today in the West as opposed to in its origin community? Curator: That's a poignant point. Its value and interpretation certainly shift based on the social and geographical setting. And the very act of displaying this in a museum transforms its function, changing it from everyday textile to valued art object for the gaze of the Global North. Editor: Yes, and the Minneapolis Institute of Art, like any institution, plays a part in this narrative too. The panel, stripped of its original communal purpose, takes on a life within the gallery—framed by lighting, curatorial text, and the expectations of the visiting public. Curator: A complex life, indeed. Thinking about this piece and its trajectory truly reveals how an object's significance extends far beyond its materiality and construction. Editor: And it pushes us to look closely, analyze carefully, and acknowledge the many intersecting forces that shape our understanding of the art around us.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Mbuti men collect pieces of the inner layer of tree bark, soak them in water, and pound them until they are thin and pliable. Mbuti women then use twigs or their fingers to decorate these canvases with intricate designs that show repetitions of a single element or various groups of motifs. The Mbuti people live in the Ituri rainforest in the northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo, and the abstract imagery in their art expresses the shapes and motions of their natural environment. The barkcloth paintings can be seen as maps of the forest, invoking trails and webs, insects and animals, leaves and shelters. Yet these visual compositions also refer to the language of Mbuti music, characterized by syncope, free improvisation, and polyrhythm. As such, the painted barkcloths become graphic soundscapes, rendering a multitude of sonic events in conjunction with silence, captured by the paintings’ negative space.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.