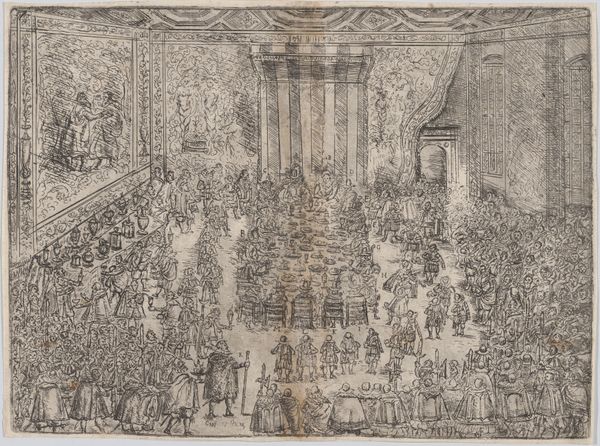

A group of young men dancing as the gods look on from above; set design from 'Il Pomo D'Oro' 1668

0:00

0:00

drawing, performance, print, etching

#

drawing

#

performance

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

figuration

#

history-painting

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 10 7/16 × 17 3/16 in. (26.5 × 43.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: What strikes me most is the ephemeral nature captured in this etching, "A group of young men dancing as the gods look on from above; set design from 'Il Pomo D'Oro'" by Matthäus Küsel, dating back to 1668. The scene depicts a performance, now lost to time. Editor: It's undeniably Baroque, but with a theatrical air! I am thinking about the conditions surrounding operatic performances in the 17th century. There's a tension between the divine and the mundane in the work's architecture that immediately attracts my attention. Curator: As an etching, it's a readily reproducible medium, which in itself speaks to a broadening accessibility of art. It lets us examine the social context of its creation and dissemination, who had access to art, to these lavish theatrical productions, and in what form. It's also a durable, almost mass-produced form compared to a singular stage. Editor: Exactly. It hints at the social hierarchies within these spectacles, too. Look at how the elite—the gods, elevated above, watching. Their presence serves as a potent reminder of authority and divine right, deeply ingrained within Baroque society and how such societal structure shapes visual imagery. Curator: The line work itself, creating such detail and scale in print, reveals a fascinating level of craft and planning, the labor embedded in the multiplication of these images. Even the paper stock, the inks—all point towards production and consumption. Editor: Yes, these etchings functioned as visual propaganda of wealth and power, circulated to solidify status. Consider how these performances reflected the political landscape of the era; these aren't just drawings, they are socio-political documents! How stagecraft served the rulers, I am sure, would be its own subject here, showing that art served to solidify societal structure at that point in time. Curator: Absolutely, and it invites us to think critically about what remnants we retain today. It's a record of lost artistic practice but one now accessed through a print housed right here at the Met. Editor: It leaves me pondering the politics of image making in this period. We only see its presence through the distribution of material now carefully secured in institutions. Thank you for unveiling it for me with your critical analysis.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.