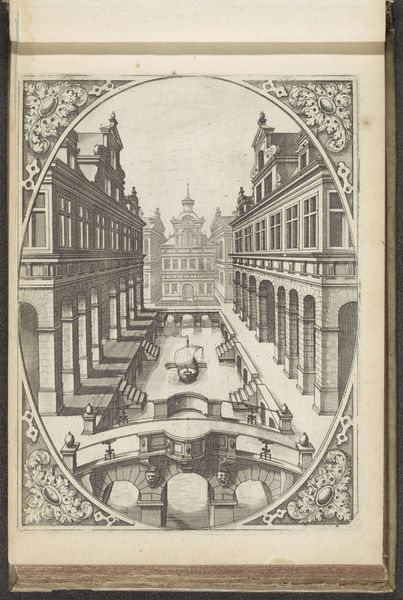

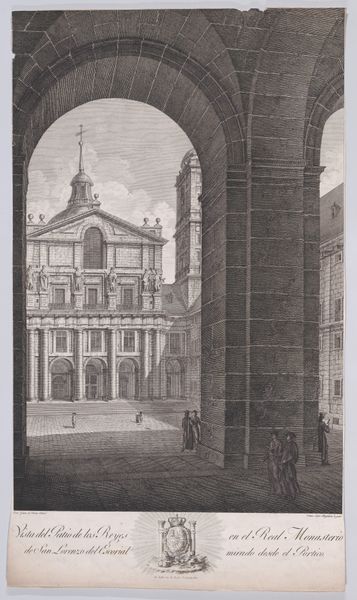

drawing, print, etching, intaglio, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

boat

# print

#

etching

#

intaglio

#

landscape

#

form

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

#

realism

#

building

Dimensions: sheet: 8 1/2 x 6 9/16 in. (21.6 x 16.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: The artwork before us, “Plate from ‘Scenographiae…’,” dates back to sometime between 1555 and 1565, originating from the Renaissance period. It's an engraving—an intaglio print by Johannes van Doetecum I. What strikes you immediately about this cityscape? Editor: The perspective. There’s this intense receding, almost suffocating architectural structure, pushing our gaze down a canal. It's as if the city is designed to constrain, not liberate, the human spirit. Curator: I see your point about constraint. Urban development during this time was very much about establishing control. Consider the patron. A print like this might have been commissioned to communicate wealth, power, order. The architecture is almost theatrical. Editor: Absolutely theatrical. I'm thinking about the relationship between architecture and performance, about how power uses the spectacle of the city to reinforce its authority. It’s a stage and we, as viewers, are relegated to the audience, gazing at this performance of control. Who exactly inhabits that space, both materially and psychologically? Curator: And it's vital to recognize that printmaking facilitated a broader distribution of such images. It played a huge part in spreading certain architectural styles and reinforcing hierarchies across geographic boundaries. There is such precision and clarity of line for that time. Editor: That's interesting. So this image becomes a kind of blueprint, exporting an ideology embedded within urban planning? It highlights the link between aesthetics and power dynamics, showcasing whose visions were—and were not—being prioritized during the Renaissance. We should definitely ask how the visual language normalizes such power structures and who benefits. Curator: The framing is quite ornamental though, somewhat softens that power by encasing this strict architecture in such delicate forms. Editor: Maybe the framing is part of the package: an ornate, decorative distraction that further obscures how urban landscapes reflect inequalities that were very real. Food for thought, anyway. Curator: A lot to unpack within what appears a relatively simple, almost quaint image. Editor: Exactly. Art offers this ongoing, often uneasy, dialogue with history. It’s not simply about beauty, but about accountability.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.