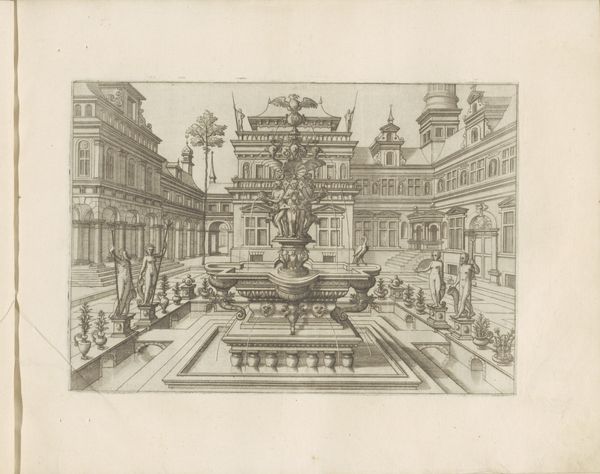

Binnentuin van een paleis met aan de façade standbeelden in muurnissen 1568

0:00

0:00

joannesvanidoetechum

Rijksmuseum

print, intaglio, engraving, architecture

# print

#

intaglio

#

landscape

#

11_renaissance

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 174 mm, width 249 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Today we’ll be discussing "Courtyard of a Palace with Statues in Niches" created in 1568 by Joannes van Doetechum, an engraving using intaglio. Editor: My first thought? Cold beauty. All those perfectly aligned shrubs, the severe symmetry... it's impressive, but there's a lack of warmth, an almost oppressive sense of order. Curator: That tension between control and beauty speaks to the function of the artwork and the politics of imagery during the Renaissance. These prints helped to disseminate ideals about power and order. Palaces weren’t just residences; they were stages. Editor: Exactly. Think about the power dynamics inherent in architecture meant to inspire awe. Consider who is granted access to this curated perfection and who is excluded. The identities solidified through control of architectural spaces are a physical and ideological representation of privilege. Who does the statue inside represent and how did they get there? Curator: Absolutely. The statues, meticulously placed in niches along the façade, aren't mere decoration. They’re signifiers, reinforcing a narrative of classical virtue, and subtly linking the patron to a lineage of power and wisdom. And of course, the medium matters. Printmaking made this kind of propaganda mobile and accessible. Editor: A calculated attempt to naturalize and make ordinary the experience of being subjugated in a public forum, something we must examine carefully through a feminist lens. Did the architectural standards take into account the safety and care of those who identify as women, nonbinary, or gender-fluid? What kind of body is invited in this rendering? Curator: These kinds of engravings created templates for wealthy merchant or aristocratic families who sought legitimacy and permanence in turbulent times. The printing medium also served to elevate architecture to the level of artistic importance found previously only in painting and sculpture. Editor: It makes you consider the ethics surrounding the deliberate curation of taste and the marginalizing impact it has on those outside the depicted aesthetic. Art doesn’t exist in a bubble; it lives in relation to all sorts of social narratives that must be interrogated to fully appreciate its meaning. Curator: An incredibly salient point, that reminds us to delve deeper. Thank you for this challenging but vital perspective. Editor: A necessary element if we truly want to create pathways for diverse viewership to critically engage in discussions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.