photography

#

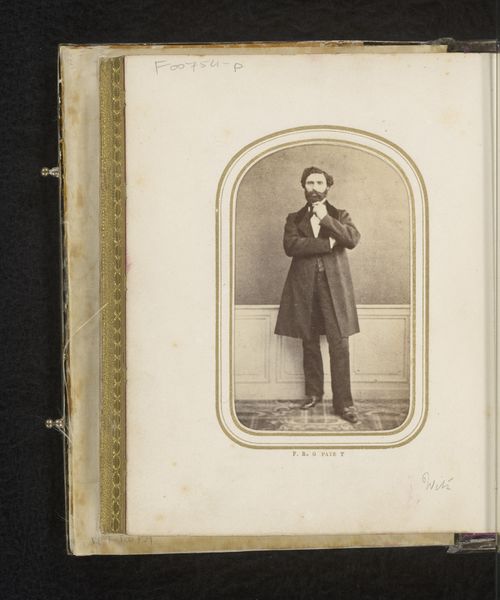

portrait

#

photography

#

genre-painting

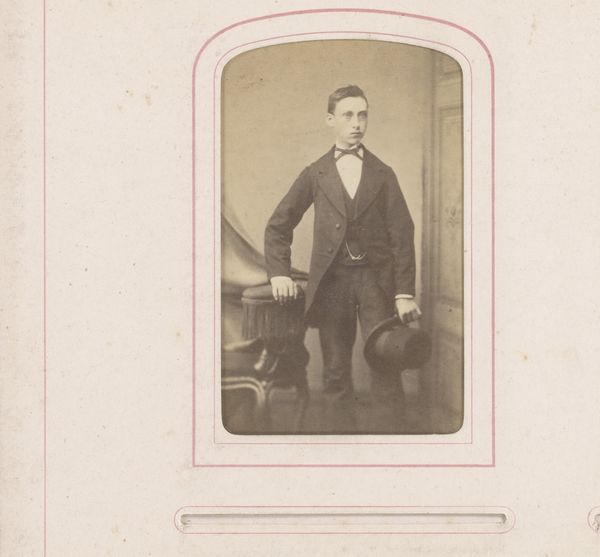

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

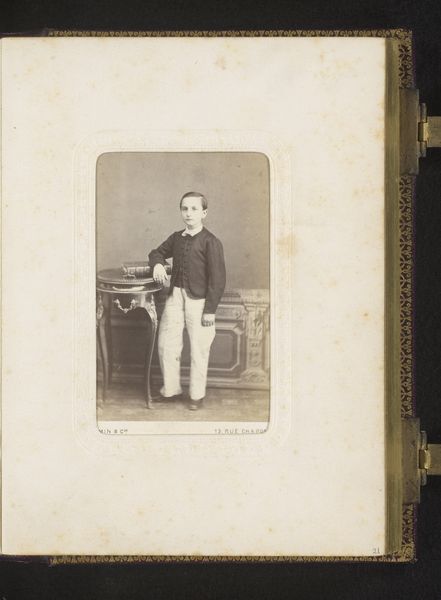

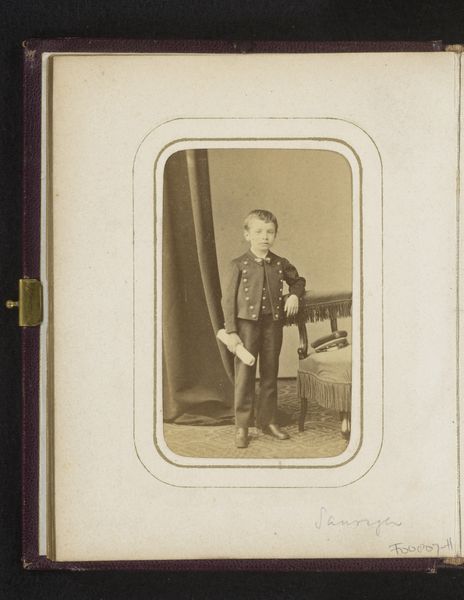

Curator: This portrait, "Portret van een jongen met bolhoed in hand bij een stoel," captures a young boy sometime between 1855 and 1892. It’s an albumen print, a popular photographic method during that era. Editor: It's rather endearing, this staged formality. The young boy looks slightly uncomfortable, yet also proud. The bowler hat resting on the chair creates an intriguing juxtaposition with his otherwise unpretentious attire. Curator: That awkwardness might be tied to the formal setting common in 19th-century portraiture. Photography was often a special occasion, meant to commemorate milestones or represent social status. He is well dressed, yes, but I imagine photography still felt foreign for many families during this time. Editor: I'm also drawn to the socio-economic implications of such images. Who had the time and resources for a portrait in this period? Certainly not the working class. This photograph offers a window into a specific class identity. It seems very deliberate. Curator: Absolutely. The inclusion of the ornate chair, as a prop and set piece, speaks to the studio’s desire to elevate the sitter’s status, even if only for the image itself. It shows how studios presented portraiture as something attainable. Editor: This reminds me of studies by Allan Sekula on the use of photography for constructing social identities. It appears this image is designed for public display, likely within the family’s home. A young bourgeois asserting his place within the social order. Curator: I hadn't considered the broader implications for consumption. Siderius seems to consciously capture and market aspiration through the domestic genre of the family portrait. It’s intriguing to note that studios made a business out of it, even normalizing its presence. Editor: It invites us to reflect on the evolution of portraiture, class representation, and photographic practices throughout time. Perhaps it provides more than just representation—but also empowerment through a very accessible product of self-making. Curator: Indeed. The power dynamics inherent in photographic representation are subtle yet powerful. Editor: It has sparked reflections on history, self-fashioning, and what portraits continue to mean today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.