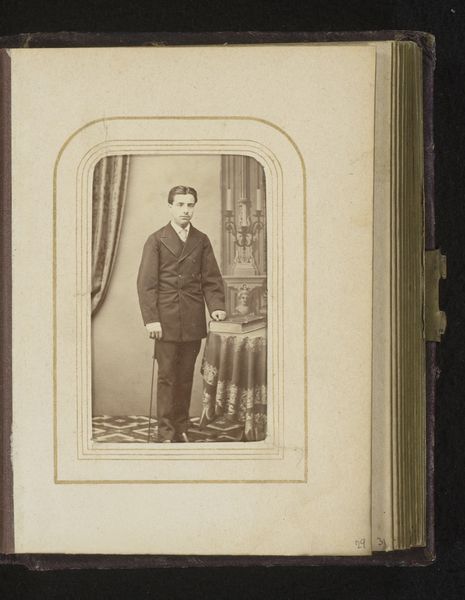

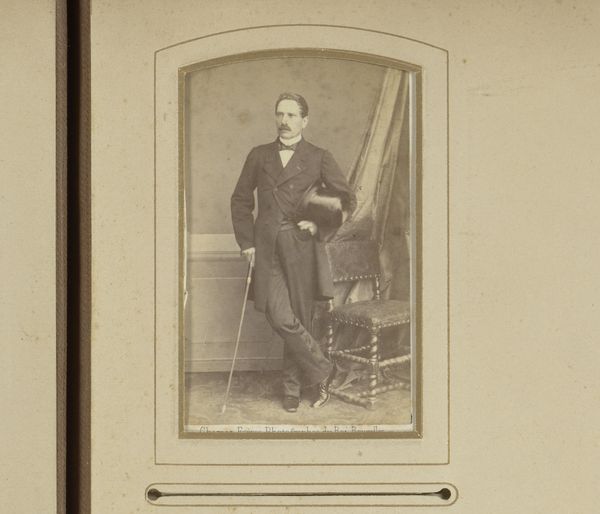

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

realism

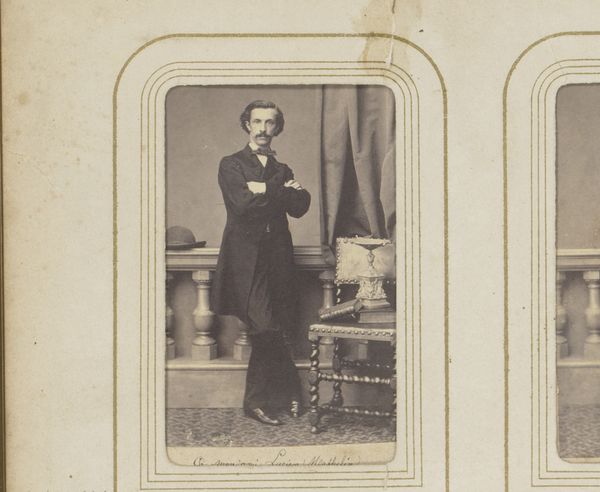

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

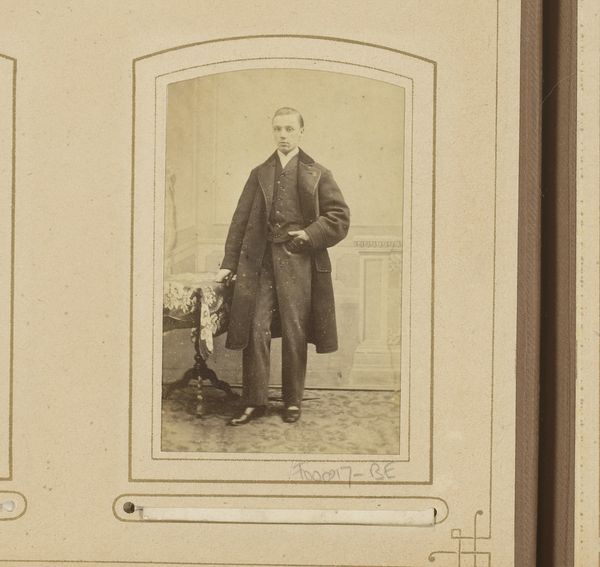

Curator: Here we have a striking daguerreotype, "Portret van een staande man met hoed in de hand, voor een tafel," dating from somewhere between 1853 and 1880. Editor: There’s a melancholic feel to this image, almost haunting. The muted tones and formal pose contribute to a sense of restraint, and he looks so very young. Curator: The conventions of early photography, certainly, enforced that stillness. It's intriguing to consider what this portrait signified in the context of mid-19th century societal norms. Posing for a daguerreotype would have been a marker of status, and this young man, holding his hat with his hand on his waist looks like a respectable member of the emerging middle class. Editor: That's a powerful point. The hat itself has its meaning; held instead of worn is interesting – does it signal an attempt at humble gentility? Curator: It's possible. We can view it as a self-conscious performance, a staged representation carefully crafted to convey a particular image. The table and book further signify status, a desire to convey intellectual weight, to establish a certain type of identity. This image shows an interesting combination of the desire to be a fashionable dandy but also the constraints and possibilities of early photographic representation. Editor: Symbolically, books often represent knowledge and status, a sort of wisdom conferred upon the subject, the draped table speaks to prosperity but almost theatrically. I’m also caught by the light. Curator: Absolutely, early photographic techniques meant that light and shadow had to be carefully manipulated to produce a likeness. The lack of colour adds a layer of symbolic weight. Editor: It speaks to its time, doesn't it? As a preserved moment, it silently evokes many layers: social position, the desire to project stability in what were undoubtedly turbulent times. The power of images is often about the layers they conceal. Curator: Exactly, and analyzing how such portraits function in their historical context helps us understand not just the sitter, but the visual language of the time and the very constructedness of identity. Editor: And that continues to resonate profoundly today. Curator: It certainly does.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.