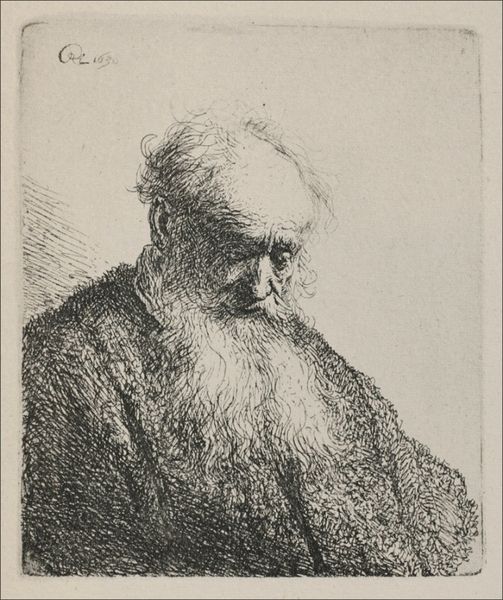

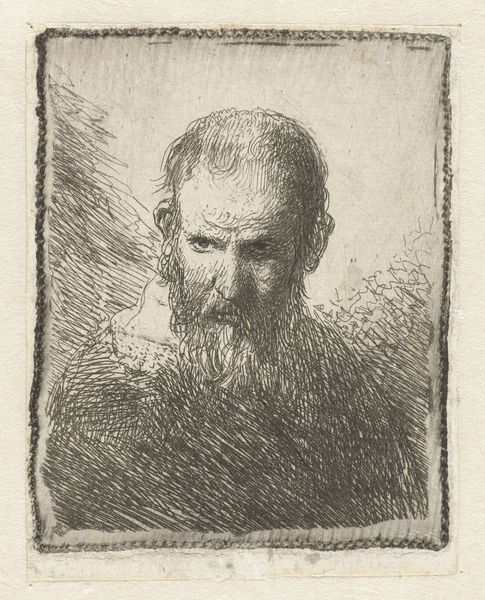

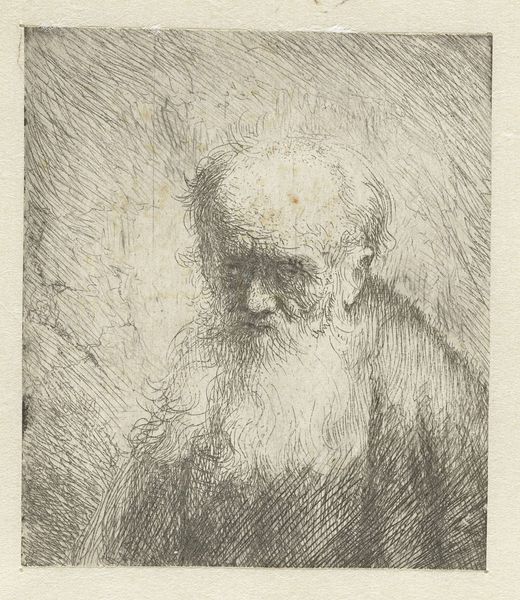

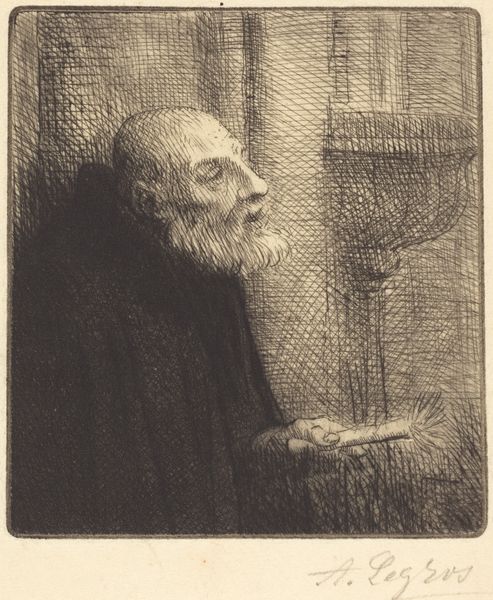

print, etching

#

portrait

#

baroque

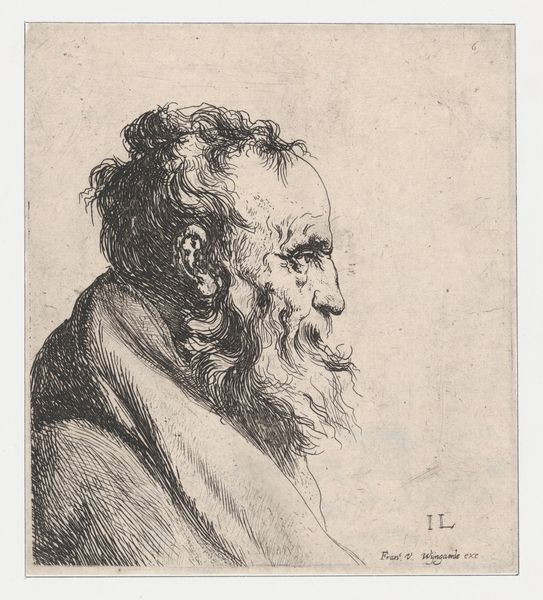

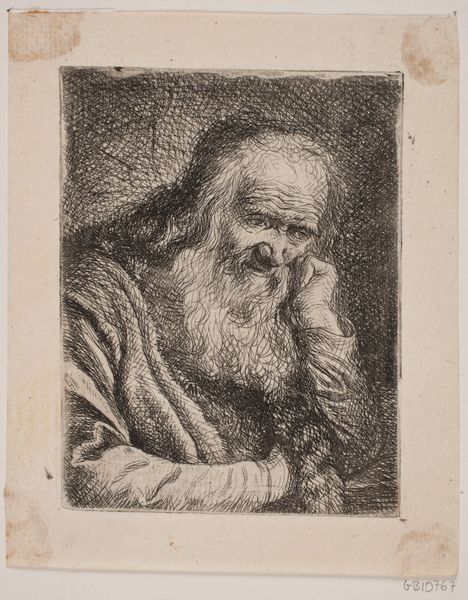

# print

#

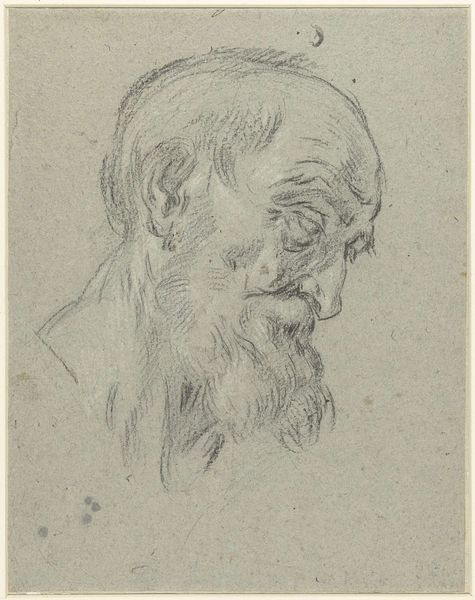

pen sketch

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

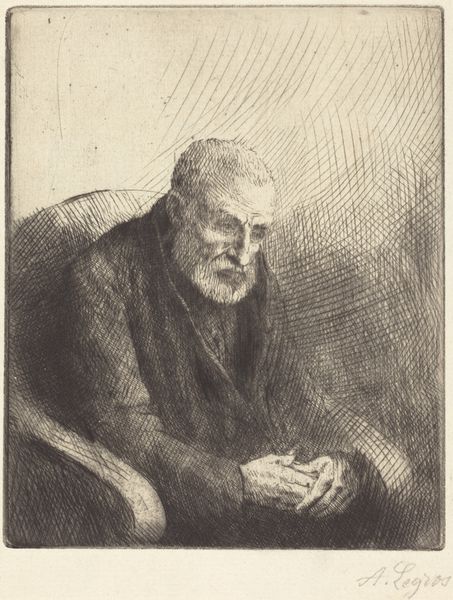

realism

Dimensions: height 108 mm, width 84 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This intriguing piece, tentatively dated between 1639 and 1706, is titled "Buste van een priester"—Bust of a Priest—created using printmaking techniques, specifically etching, by Pieter Rottermondt. Editor: What strikes me immediately is the incredible vulnerability in this image. The lines, like whispered secrets, reveal a weary soul bowed with age or burdened by knowledge. It’s haunting. Curator: Absolutely. Etching, especially in Rottermondt's hand, offers a fascinating study in reproducible images, considering the class structures of art consumption in 17th century Netherlands, making such portraiture potentially accessible to a wider market beyond the traditional patrons. Editor: True. The way he uses cross-hatching creates a remarkable texture. The beard feels almost tangible, as though I could reach out and feel the roughness. Is it the realism mixed with that scratchy Baroque drama that's got me? Curator: That balance is key, wouldn't you say? The detailed realism pulls us into the individual, but the visible process of etching, the lines themselves, highlight the labor involved in art making. These materials carry significance, influencing reception. Editor: He really captured a mood. I get the sense this priest, or perhaps a depiction of the everyday person, is contemplative. It's as if he’s withdrawn into himself, seeking answers, or maybe just a moment's peace. I want to hear his story, the history of his very clothes and worn skin. Curator: Rottermondt seems to comment on that very everyday existence through the printmaking's inherent multiplication, which transforms how people related to art. I wonder what his motivations were? This was the workshop production writ small. Editor: And he doesn't shy from portraying every wrinkle, every sag—a stark and unfiltered observation on aging, but I believe Rottermondt found dignity there. A portrait doesn't always need to flatter; truth itself has its beauty. Curator: The social context then clearly indicates shifts in artisanal production, with individualized styles taking prominence. I think that changes what people could do with art and how art made things possible for them. Editor: This makes me consider who are we remembering? That is, Rottermondt the artist or perhaps the sitter themselves. Who knew a simple portrait of a clergyman could lead to so many rabbit holes to tumble down!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.