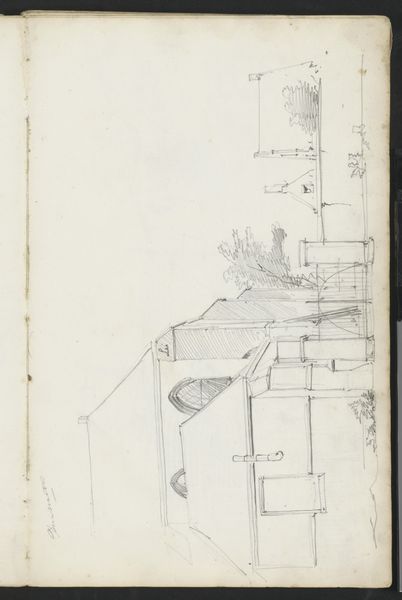

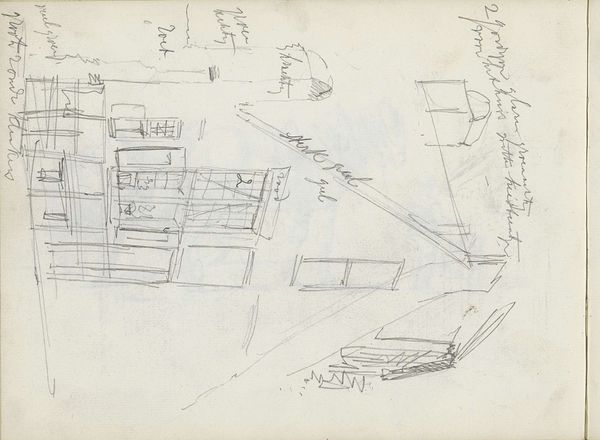

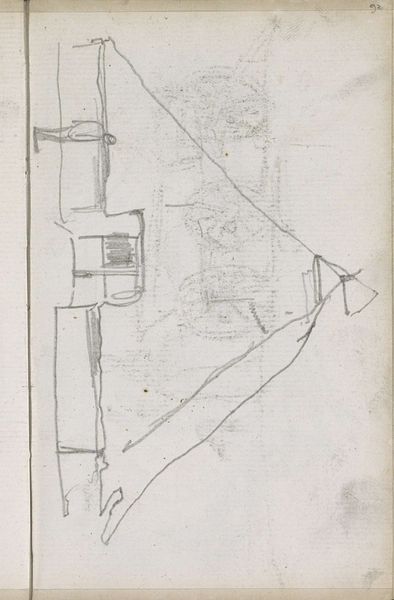

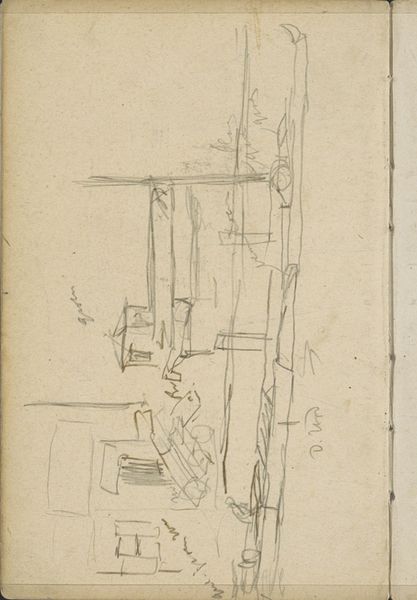

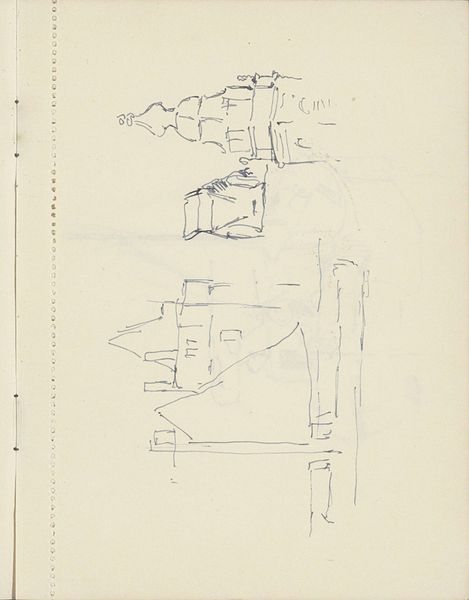

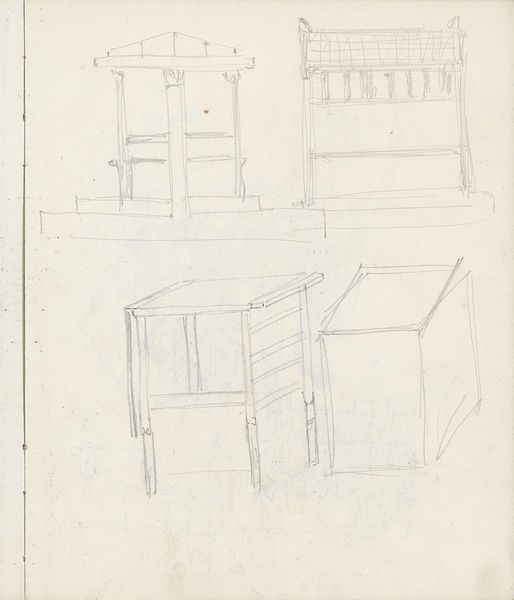

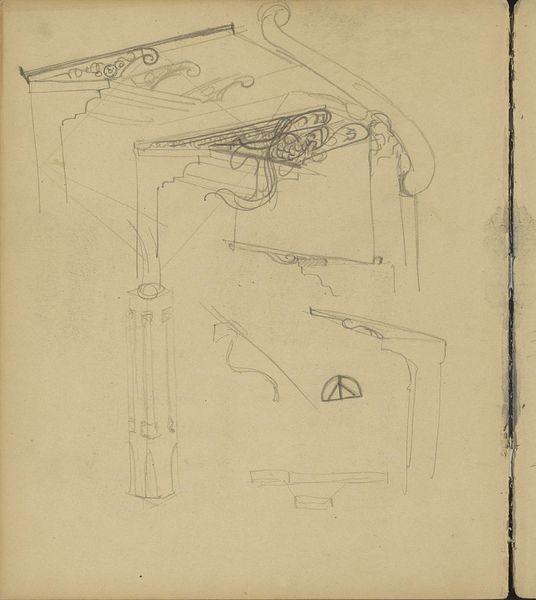

drawing, paper, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

paper

#

form

#

geometric

#

pencil

#

line

#

modernism

#

architecture

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

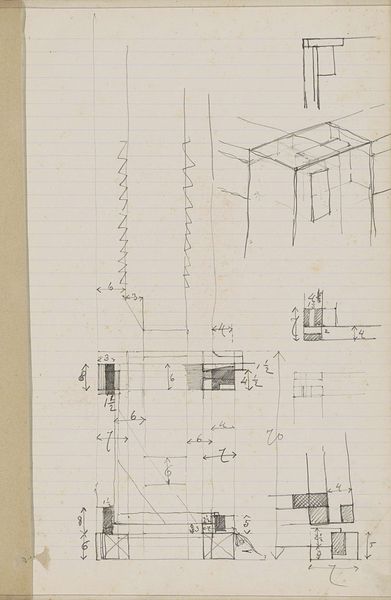

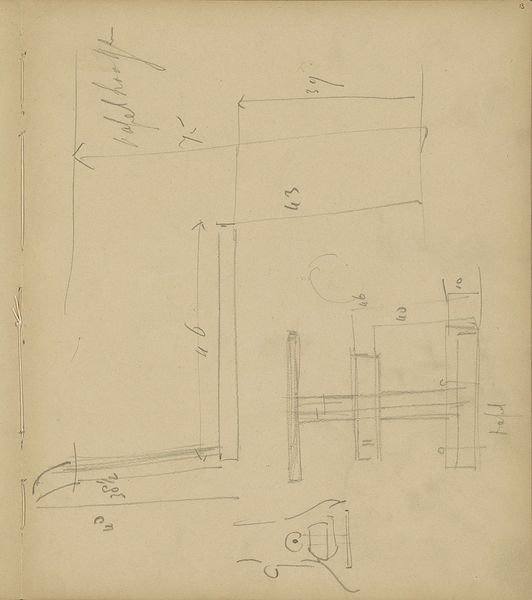

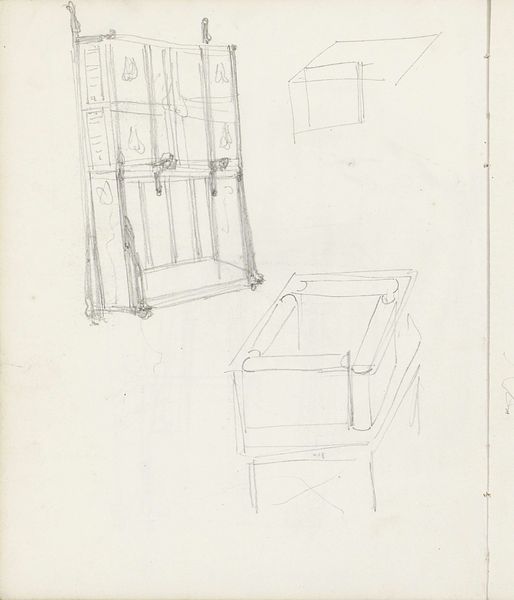

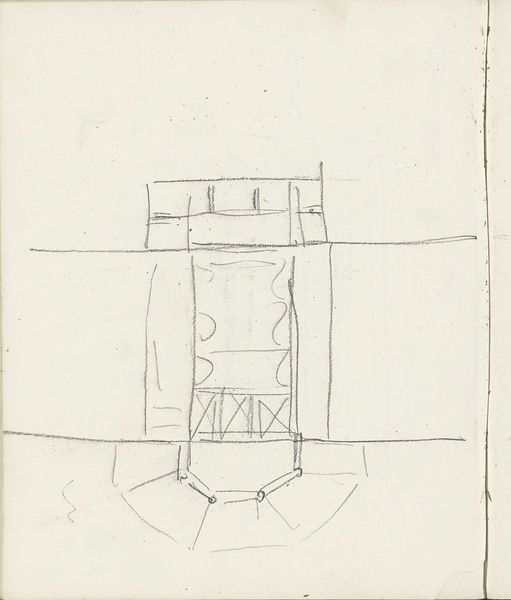

Curator: Immediately, this drawing feels both incredibly modern and strangely incomplete. Editor: You're right, there's a stark simplicity to it. This is “Meubelontwerp,” or "Furniture Design," a pencil drawing on paper, created around 1901 by Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What are your initial thoughts beyond incompleteness? Curator: I think what strikes me is the artist's focus on geometric forms and line. The drawing captures the bare bones of a design—but what kind of social relations and interactions might be facilitated or constrained by such stark, angular furniture? Who would benefit from such an aesthetic? It hints at the austerity embraced by certain factions within the Modernist movement. Editor: It is a striking demonstration of early modernist sensibilities; line becomes form, architecture becomes art. I see in this period a profound shift in the role of the artist and the designer—Dijsselhof saw beyond the individual piece and envisioned total environments. He sought to create spaces and objects that harmonized and influenced society. Curator: Precisely. But for whom? That’s where I become more critical. Modernism, at times, promoted universal principles, often masking its own deeply embedded cultural and class biases. Who felt alienated, or erased, by this aesthetic revolution, and who got to participate? The design seems to demand a certain cultivated detachment. Editor: An excellent point. The social history surrounding the Werkbund and similar movements of the era reveal complex power dynamics. These were often spaces dominated by male figures in design and architecture, who sometimes overlooked female consumers and female designers in their production and manufacturing activities. Do you agree with that? Curator: Absolutely. While movements sought progressive reform, their vision of progress often wasn't applied evenly. Designs such as this reflect this complexity. It might appeal to us formally now, but it also provokes questions about historical exclusions, access to this cultural realm. Editor: Looking closely now, I’m fascinated by the deliberate rendering of depth using line alone—Dijsselhof’s draftsmanship really shines. It reminds me how the power of preliminary sketches—this "underdrawing"—often remains hidden. The finished piece may never even see the light of day. Curator: Yet this preliminary drawing, incomplete as it may seem, stands here now at the Rijksmuseum, beckoning viewers to consider larger cultural structures that shape design. It encourages a reflection of progress through visual and material cultures. Editor: Yes, a subtle reminder that behind every artifact, behind every aesthetic decision, is a nexus of complex forces.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.