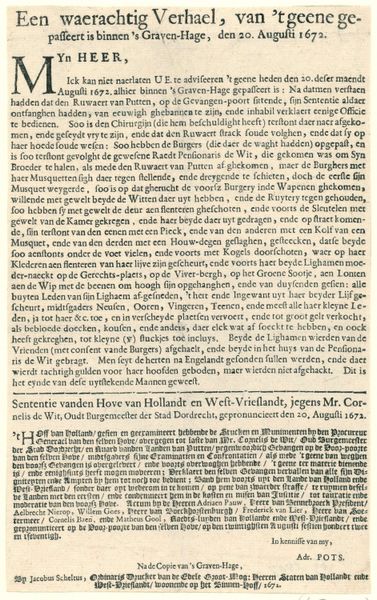

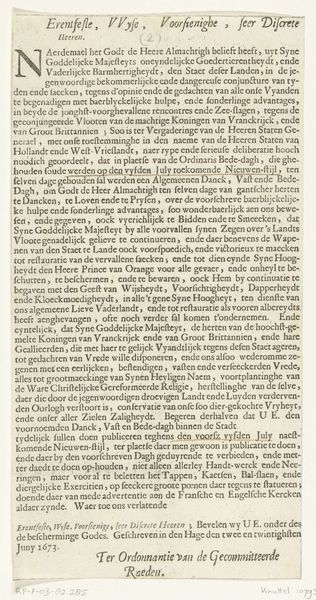

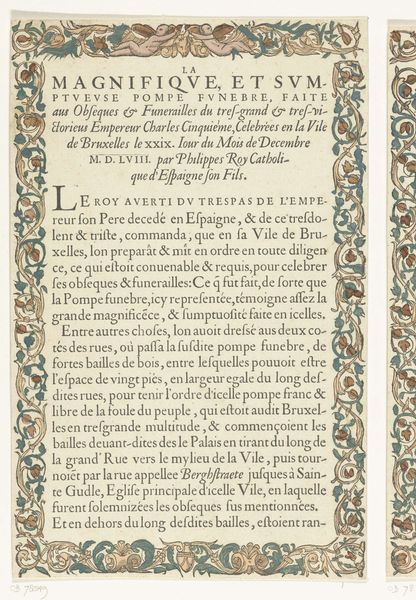

Tekstblad bij de prent met de allegorie op de aanvaarding van het stadhouderschap door prins Willem V, 1766 1765

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 273 mm, width 167 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

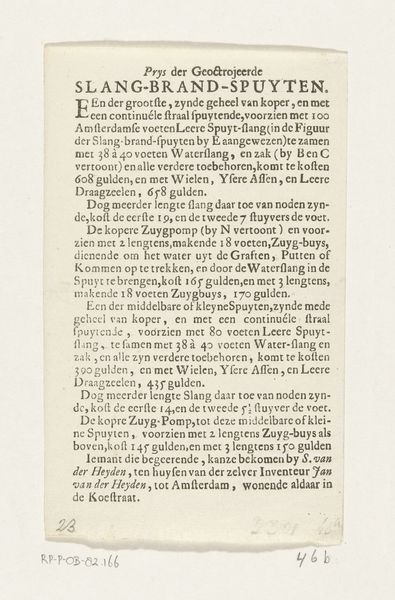

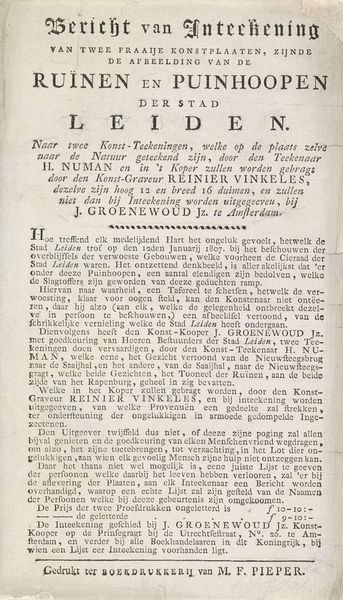

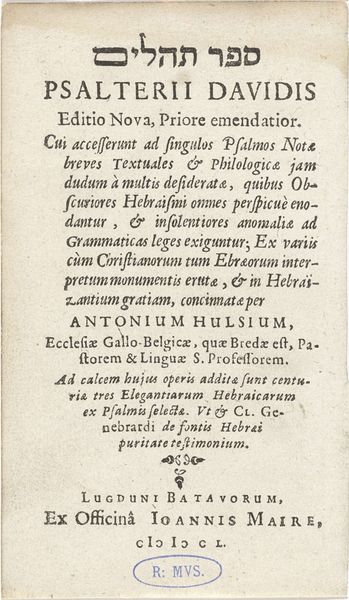

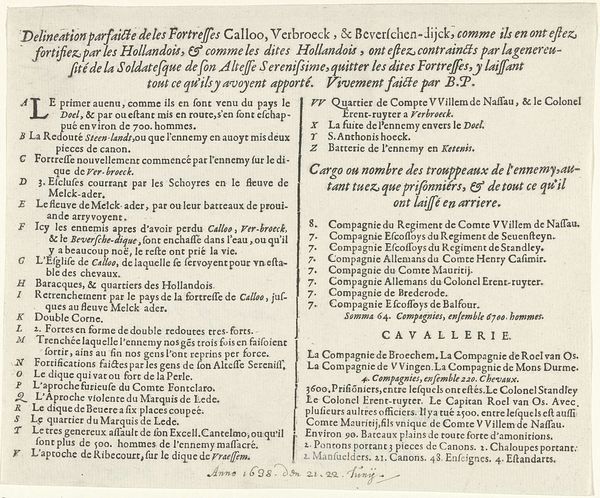

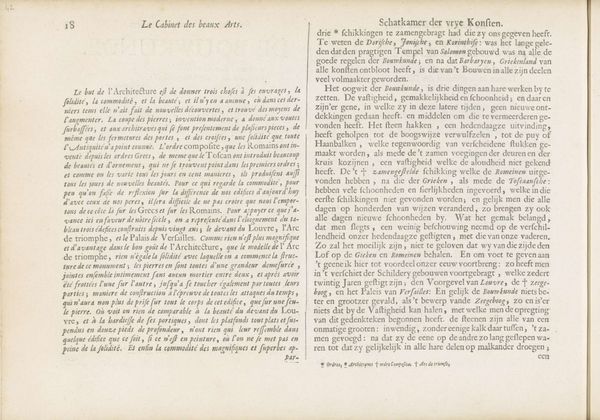

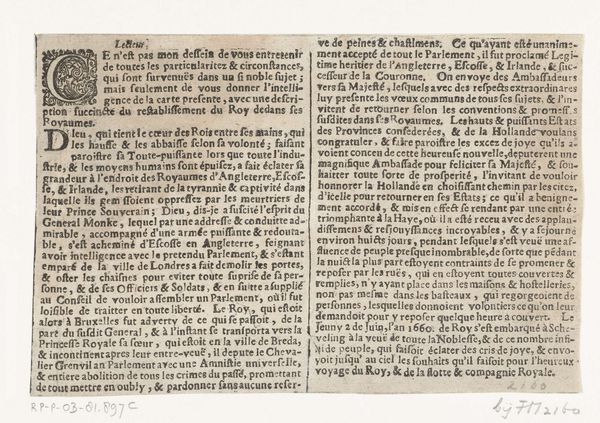

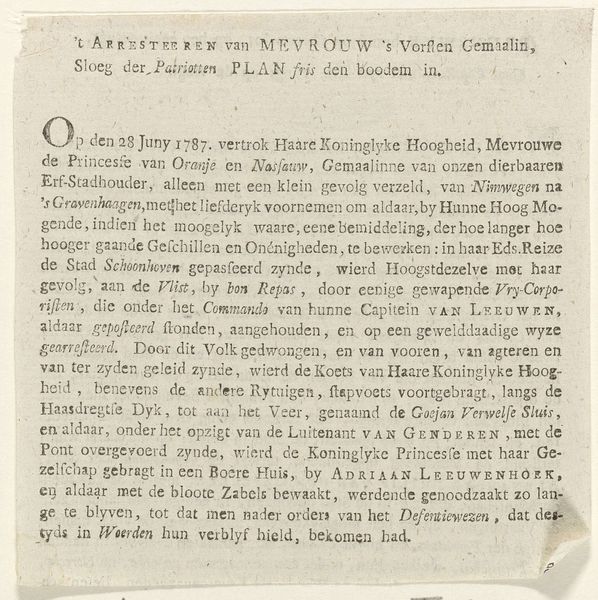

Curator: This printed text, created around 1765, lives at the Rijksmuseum. The museum calls it a "Text accompanying the print with the allegory on the acceptance of the Stadtholderate by Prince William V, 1766." What is your initial take? Editor: Woah, that is a mouthful of a title. My first impression is just how visually dense this is. It almost looks like an abstract composition; the letterforms themselves become the art. The lack of visual breathing room is a choice, an aggressive statement! Curator: Indeed. It functions as an explanation, a key to understanding a companion engraving by an anonymous artist commemorating Prince William V's ascension. This would be a Baroque-style print; allegorical prints like this served as political tools. Editor: So, reading between the lines – no pun intended – this isn’t just explaining art, it's explaining power. The language… Magnanimity, piety, fidelity… it reads like pure propaganda. “Liberty holds the chains broken by the Prince’s ancestors”… Give me a break. Curator: The language is definitely constructing a narrative of legitimacy. We see classic baroque imagery, divine justice descending, monsters of fanaticism and discord underfoot… The text painstakingly details how the prince’s rule ushers in an era of virtue and prosperity. The print would depict these concepts visually. Editor: And by explicitly describing the allegory, they control its interpretation. No room for nuance. But even acknowledging that it’s propaganda, you can appreciate its power. Curator: It absolutely reflects the socio-political climate. This acceptance of the Stadtholderate represented a pivotal moment in Dutch history, and this print attempts to cement a specific version of that narrative. Consider the role of the anonymous artist here; they were a pawn in this game of image construction. Editor: Thinking about the time, before mass literacy, images like this probably carried real weight. The visual language and these explanatory texts had a captive audience. But stripped of that original purpose, it becomes a strange sort of time capsule, where we see propaganda fossilized as art. Curator: Precisely. Its power lies in its revelation of historical values, anxieties, and strategies of persuasion. Close examination of the language helps to pull back the curtain, revealing those structures of power. Editor: So, beyond just deciphering baroque allegories, it’s about uncovering power dynamics, hidden in plain sight. Literally. Makes you wonder what texts *we’re* blindly consuming today, right?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.