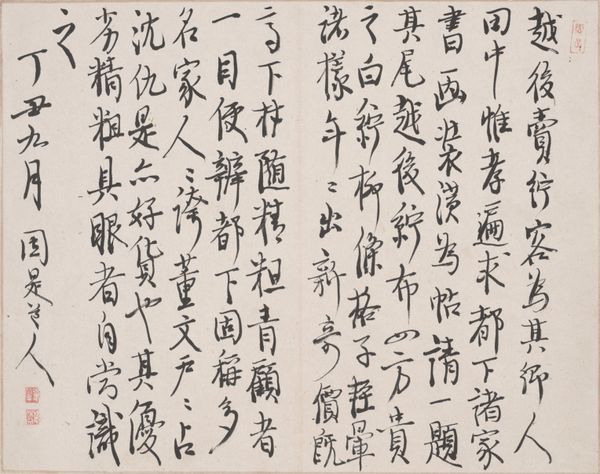

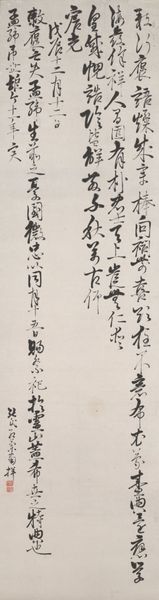

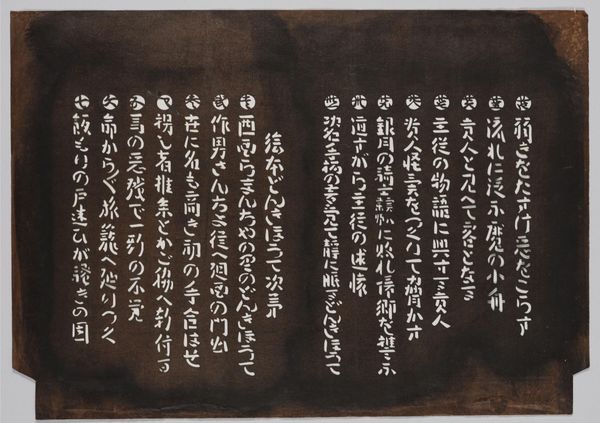

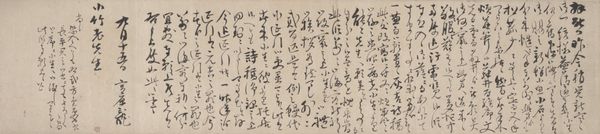

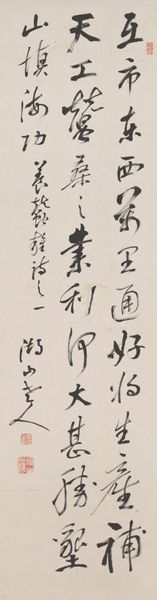

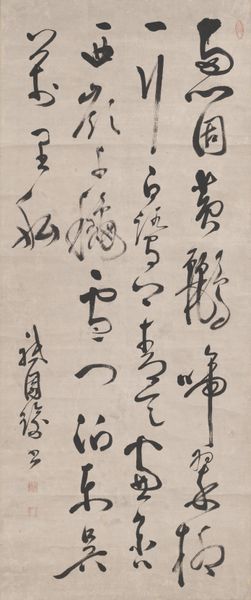

drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

asian-art

#

ink

#

line

#

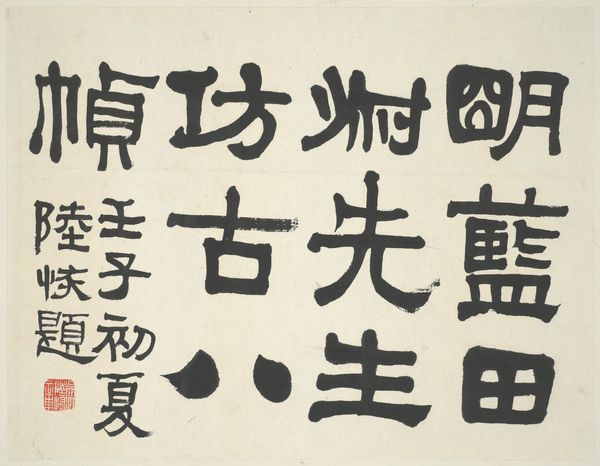

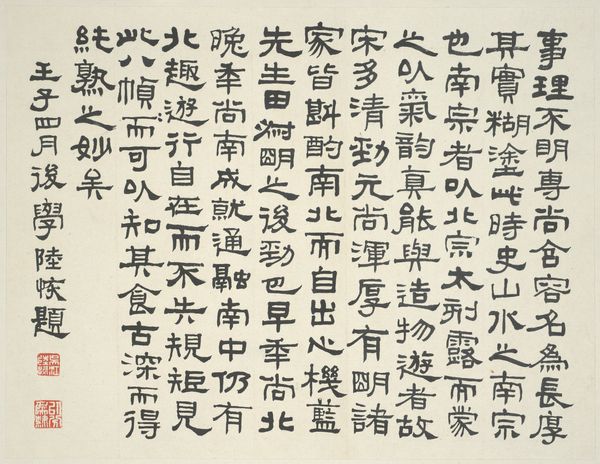

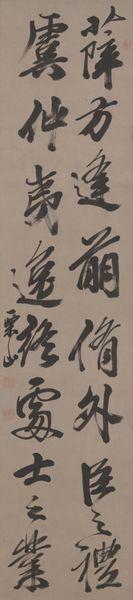

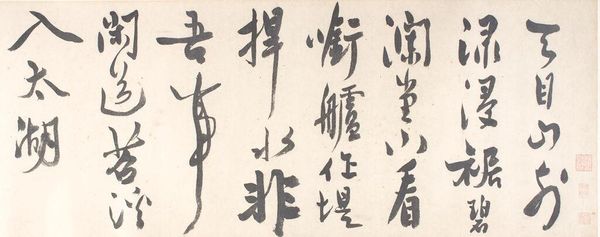

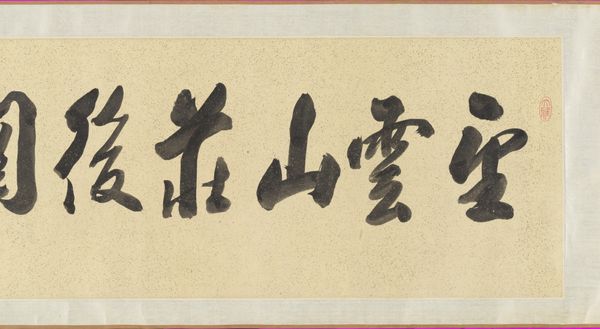

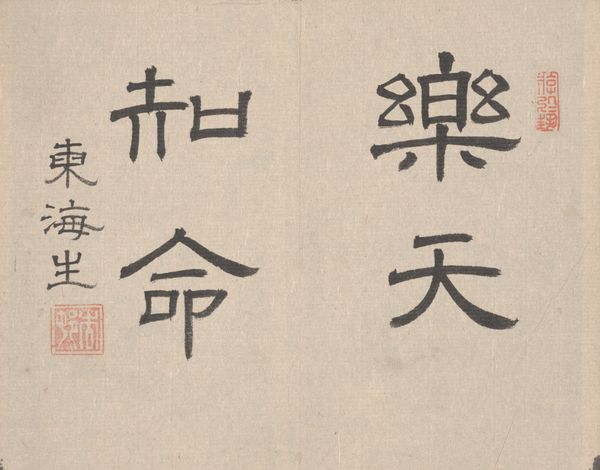

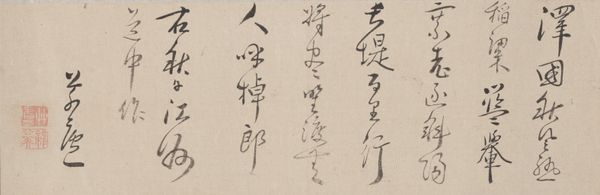

calligraphy

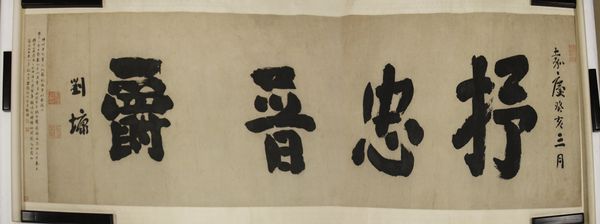

Dimensions: Image: 13 7/8 x 282 5/8 in. (35.2 x 717.9 cm) Overall with mounting: 14 1/2 x 457 1/8 in. (36.8 x 1161.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: What immediately strikes me about this work, Wang Shu’s “Calligraphy after Three Texts by Yan Zhenqing,” created in 1729, is its almost stark simplicity. The Metropolitan Museum of Art houses it, and looking at this drawing crafted with ink, one feels a palpable sense of austerity and focused energy. Editor: Austerity? I see something…well, more mischievous, actually. The characters almost seem to be dancing, wobbling in place. Maybe austerity laced with a bit of ironic humor. Curator: It's important to consider the cultural weight it carries. Yan Zhenqing was a hugely important figure in Chinese calligraphy, revered not only for his artistic skill but also for his loyalty and integrity as an official. Wang Shu, centuries later, engages with that legacy. This isn't just copying; it's a dialogue across time. He lived in an era defined by Manchu rule, where embracing or reinterpreting past traditions held subtle, sometimes subversive, meanings. Editor: Subversive dancing characters! I like that narrative. The sheer *confidence* of each stroke—thin, unwavering lines yet…off-kilter, ever so slightly. There’s breathing room around each form, a sense of quiet spaciousness, almost a question of its own perfection. Does this reverence demand rigidity or offer room for reimagining? Curator: The form of calligraphy itself held enormous significance. For the scholar-official class, like both Yan Zhenqing and, later, Wang Shu, mastering calligraphy was essential. It demonstrated not just aesthetic ability but also moral character and education. The precise rendering, the control of the brush—all reflected inner discipline. Therefore, a choice like imitation of another artist reflects allegiance to specific scholarly lineages and cultural values. Editor: I see the discipline now, that underlying control, like an elegant chess player executing a risky gambit. These reinterpretations of classical art styles are full of historical contexts, creating an intimate space between honoring traditions while challenging them. Maybe it's not just about rewriting history but sketching it with new inflections. Curator: Exactly. I feel the echo of generations contained in those inky lines. Wang Shu uses art to converse and confront prevailing historical themes with an exquisite sense of detail. Editor: Absolutely! It reminds me to allow art to hold these open dialogues that reverberate and reframe what exists beyond present perception.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.