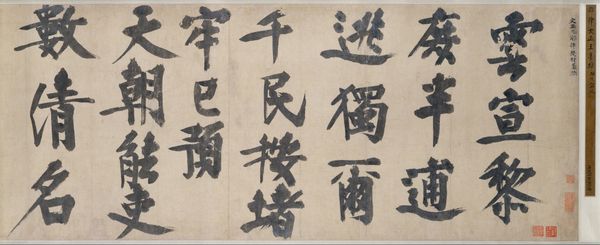

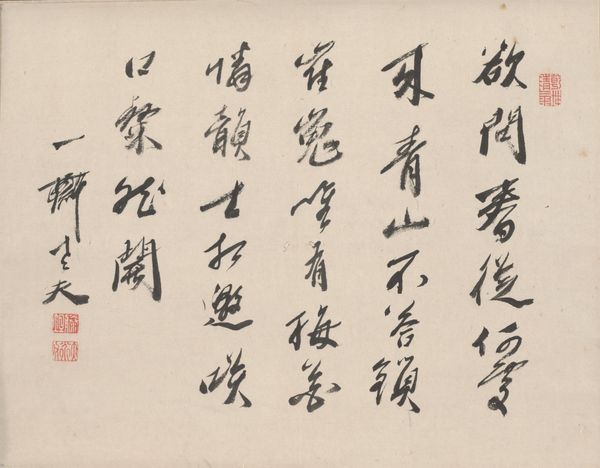

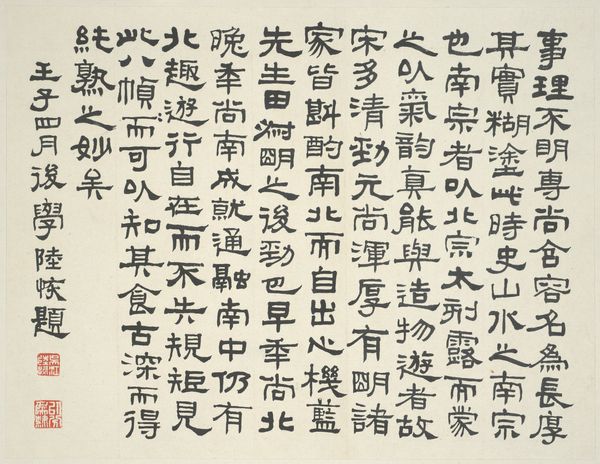

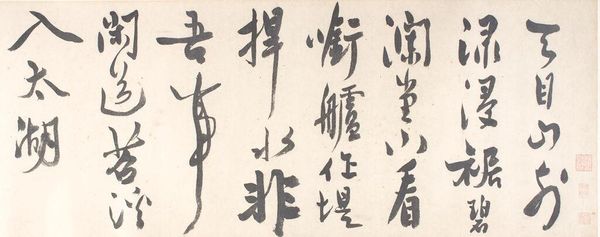

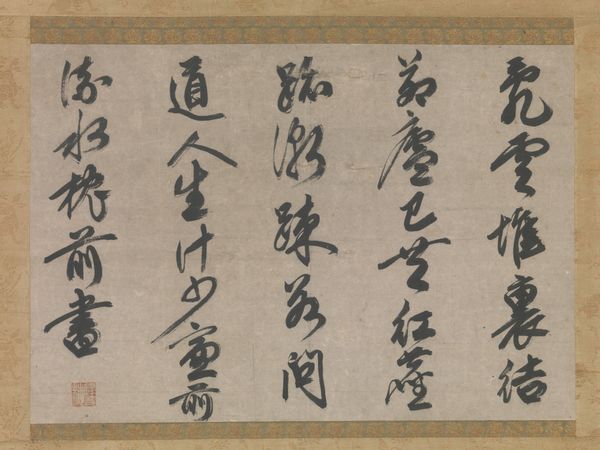

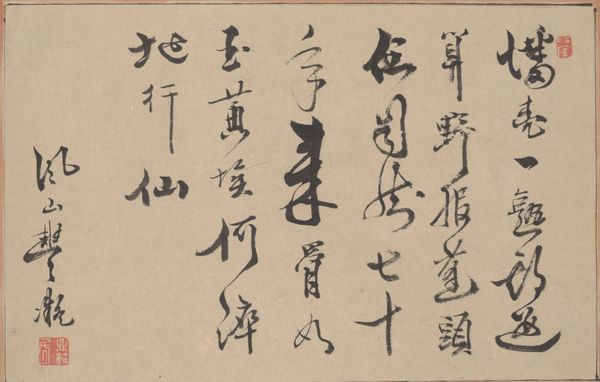

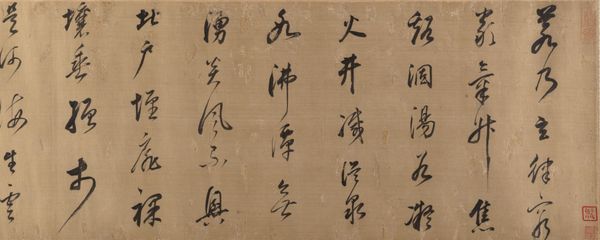

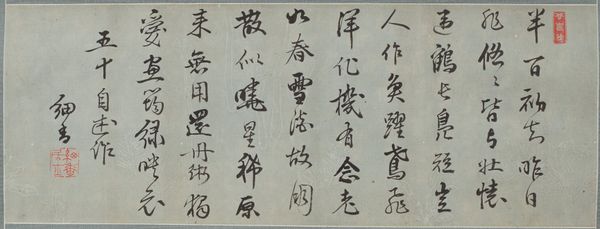

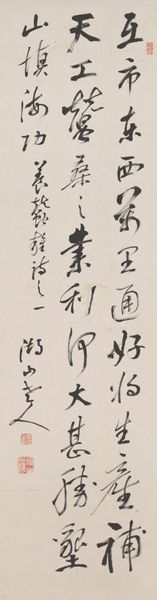

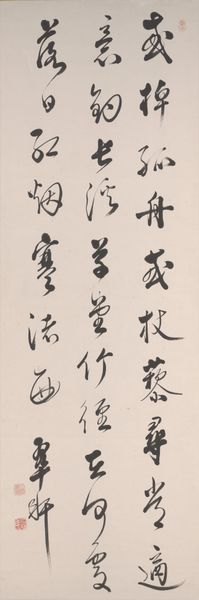

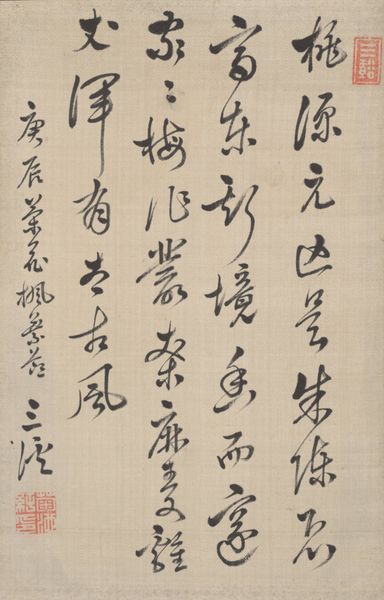

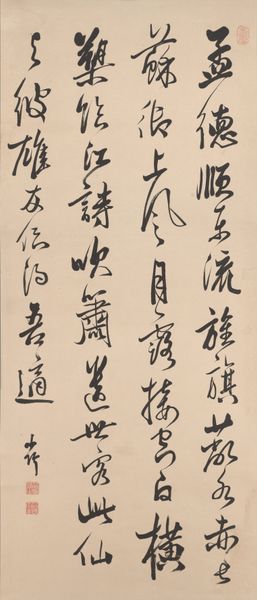

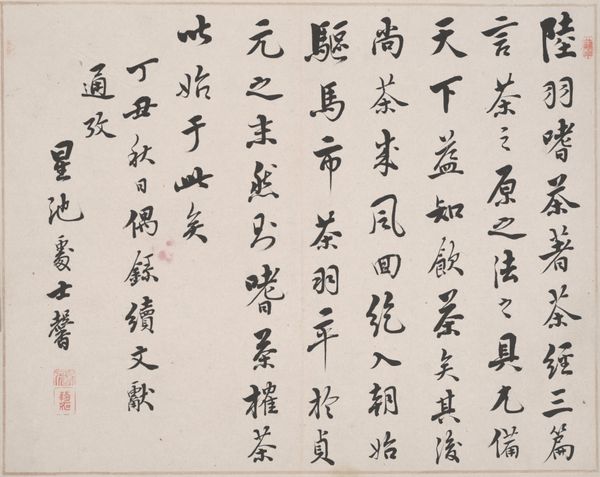

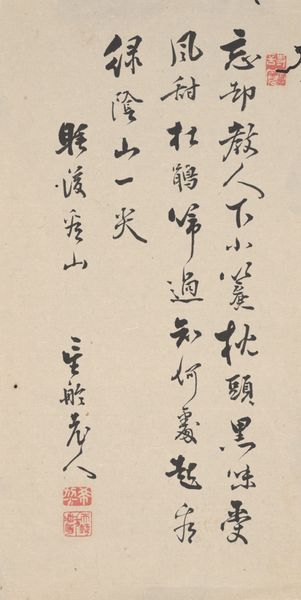

Landscape in the Style of Ancient Masters: frontispiece title by Lu Hui (1851-1920) Possibly 1368 - 1644

0:00

0:00

paper, ink

#

asian-art

#

leaf

#

paper

#

ink

#

geometric

#

abstraction

#

china

#

line

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: 31 × 40.7 cm (12 × 16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let's turn our attention to this fascinating piece, “Landscape in the Style of Ancient Masters: frontispiece title” possibly from the Ming Dynasty and created by Lu Hui. It’s ink on paper, currently held here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the materiality. Look at the deliberate weight and texture of the ink, each stroke a tangible action on the page. There's such density. Curator: Precisely! Lu Hui is consciously situating himself within a historical tradition, referencing earlier landscape masters through calligraphy. Consider how deeply ingrained art history is within artistic practice in China. It’s about legitimizing the present through connections to the past. Editor: Absolutely. But it's also about the labor. Think of the precise brushstrokes, the physical discipline required to create those forms. This isn't just symbolic; it's evidence of hours spent honing a craft. Curator: Yes, and calligraphy’s role extended far beyond mere decoration. It functioned as a vital means of communication and expression for the elite literati class, serving religious, administrative, and cultural functions within a highly stratified society. Editor: And note the abstraction! These aren't realistic depictions of landscapes, but ideograms, representations of ideas crafted through very specific materials and processes available to a limited social class. Curator: Right, calligraphy carried a huge amount of cultural prestige. This piece acted not just as a title but to situate the paintings that followed within a discourse of scholarly ideals and aesthetic refinement. The purpose of creating an elevated, cultural experience becomes very clear. Editor: What is interesting to me, in looking at the material, is the interplay of the dense ink with the absorbing character of the paper, where both dictate the form the final character adopts and creates a sense of both fragility and strength at the same time. Curator: Indeed. Examining works such as these can expose how the literati class sought to shape narratives about art, history, and their place in society, giving insight into the cultural priorities of the era. Editor: By understanding the materials and processes involved, we can recognize how artistic creation intersects with labor, class, and systems of value within Chinese history. Curator: It seems to be an essential tension here—between honoring tradition and demonstrating the agency of artistic execution. Editor: Ultimately, viewing art in terms of material processes lets us decode even its social context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.