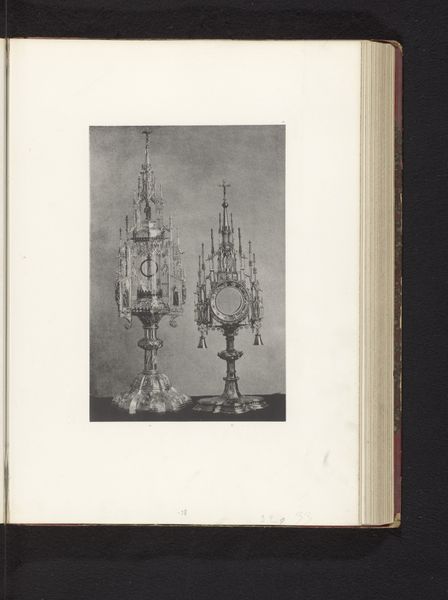

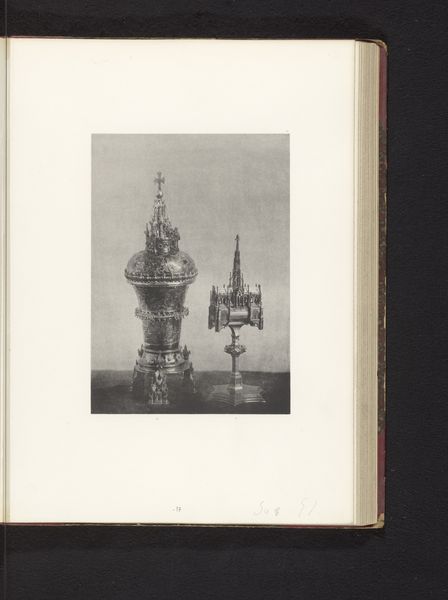

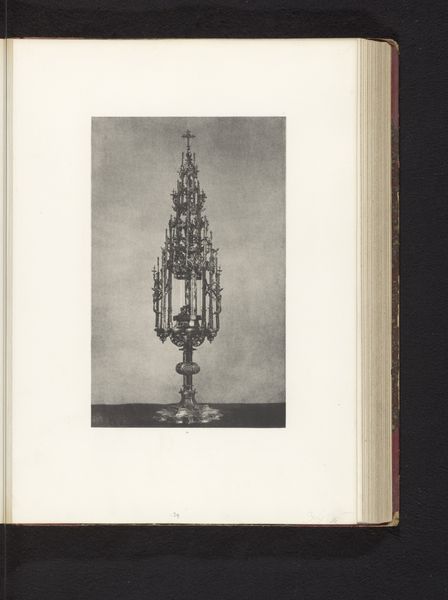

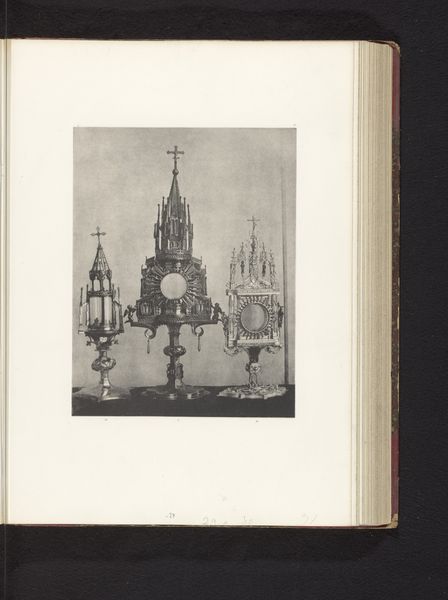

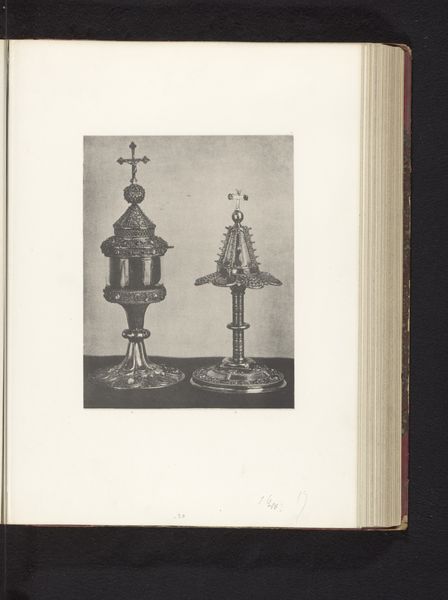

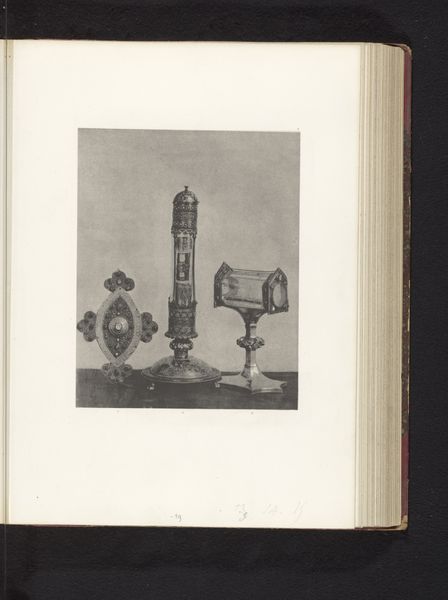

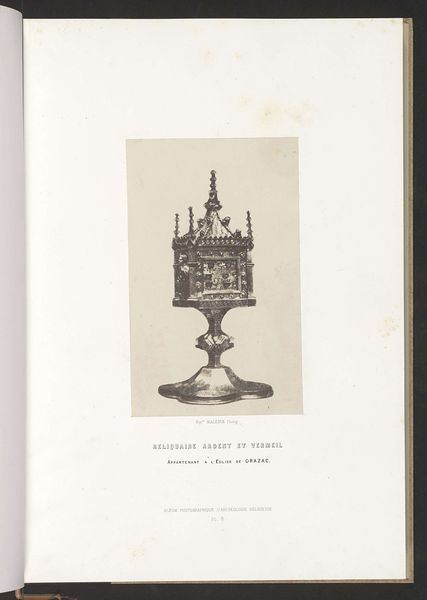

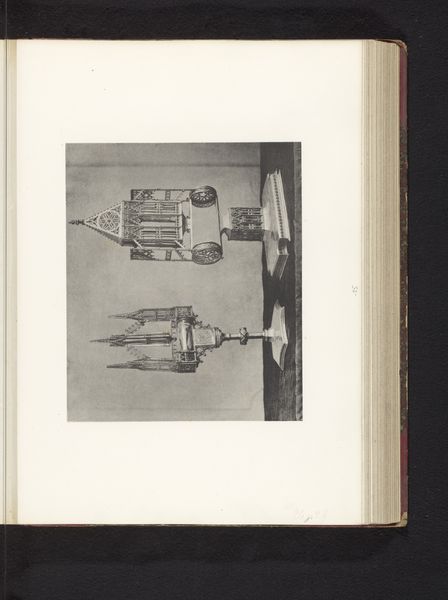

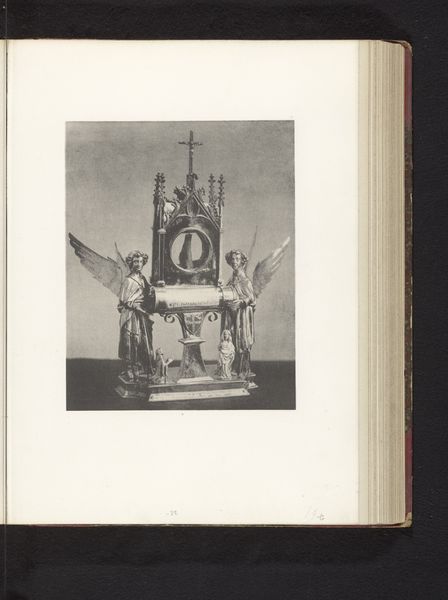

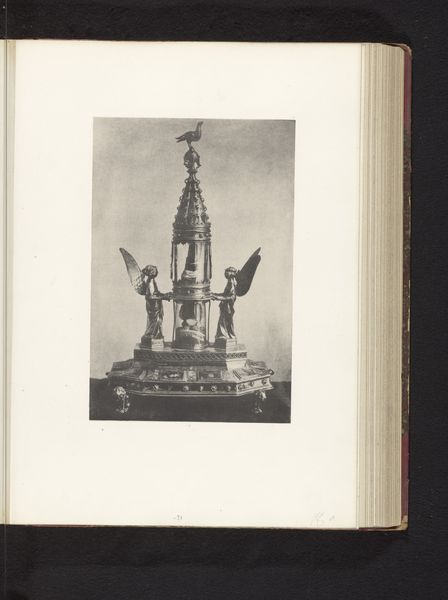

Twee vergulde monstransen, opgesteld op een tentoonstelling over religieuze objecten uit de middeleeuwen en renaissance in 1864 in Mechelen before 1866

0:00

0:00

silver, print, metal, photography

#

medieval

#

silver

# print

#

metal

#

photography

Dimensions: height 255 mm, width 169 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we see a photograph by Joseph Maes dating back to around 1864-1866. The print depicts two gilded monstrances showcased at an exhibition in Mechelen, featuring religious objects from the medieval and Renaissance periods. They appear to be crafted from silver and other metals. Editor: Immediately, the austere composition and sharp contrasts strike me. There’s an inherent stillness, an almost reverential silence captured in this image of objects meant for spiritual display. Curator: Indeed, the objects themselves are designed to command reverence. The monstrance, historically, became incredibly significant during the late medieval period and the Counter-Reformation, embodying the very presence of the divine for believers. It’s a physical manifestation of faith heavily shaped by social and theological changes. Editor: Precisely. I am thinking of how these objects are potent symbols not just of faith, but also of power. Who commissioned them? Who controlled their display? This photo also inadvertently shows us how religious symbols become recontextualized when displayed in spaces like 19th-century exhibitions, prompting me to consider how their original intent might be re-evaluated, or even subverted. Curator: That's a critical observation. In this historical moment, we see a re-framing of medieval and Renaissance craftsmanship. Displaying them within this exhibition context, it turns sacred objects into examples of artistic and historical achievements, potentially overlooking the intense theological debates and societal hierarchies from which they emerged. Editor: Which leads us to ask questions about accessibility, right? Were these objects truly for the people, or did their golden veneer mask systems of exclusion, class division, or even oppression of differing beliefs during their active usage? Considering access—who had access to see these objects back in the Middle Ages versus who got access in a 19th-century exhibit like this? Curator: Absolutely. Their function transforms. They move from being active participants in religious life to objects of study, potentially contributing to a sense of national or cultural pride, or even, perhaps, to bolstering colonial narratives by displaying the opulence and artistry of European religious traditions. Editor: Yes, it forces us to examine not just religious shifts, but socio-political ones too. Art history provides a window into understanding the legacies and lingering repercussions of colonialism, class struggle, religious intolerance and many kinds of symbolic oppression. Curator: Agreed. Examining the historical exhibition is revealing of its cultural environment. What these objects communicated then is markedly different than what they signify in our present era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.