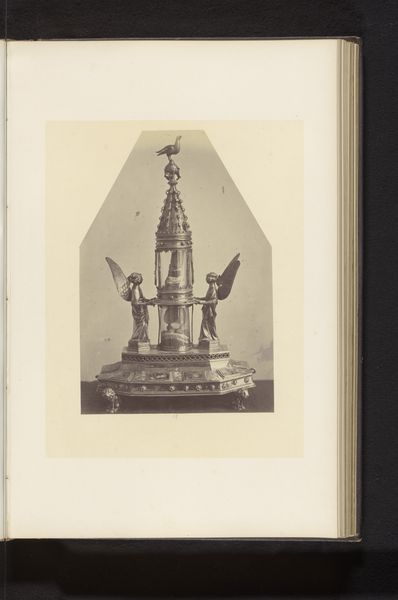

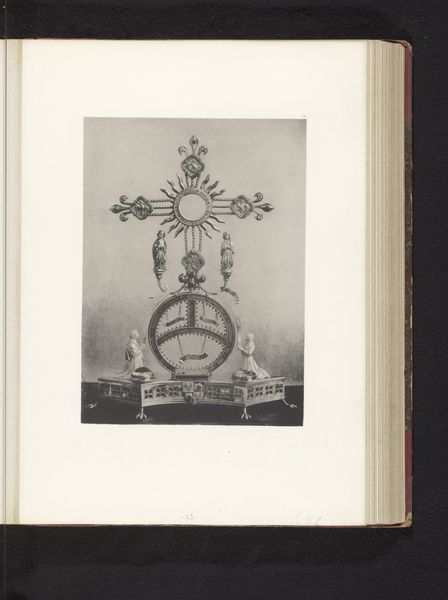

Monstrans uit de Onze-Lieve-Vrouwebasiliek in Tongeren, opgesteld op een tentoonstelling over religieuze objecten uit de middeleeuwen en renaissance in 1864 in Mechelen before 1866

0:00

0:00

#

aged paper

#

homemade paper

#

sketch book

#

hand drawn type

#

personal journal design

#

paper texture

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 262 mm, width 174 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

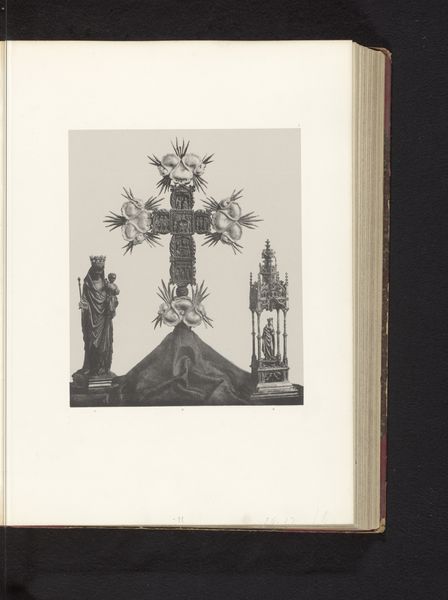

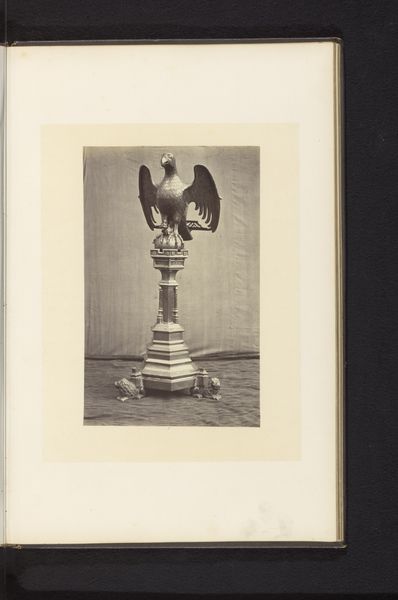

Curator: Here we have an image titled "Monstrans uit de Onze-Lieve-Vrouwebasiliek in Tongeren, opgesteld op een tentoonstelling over religieuze objecten uit de middeleeuwen en renaissance in 1864 in Mechelen." The photograph, attributed to Joseph Maes, shows a monstrance displayed at a religious objects exhibition sometime before 1866. What are your first thoughts? Editor: There’s a stark stillness to it. It feels like peering into a lost world, or maybe a world carefully curated to appear lost. The photograph’s composition draws the eye upward along the vertical axis of the monstrance toward that delicate dove at the top. Curator: Precisely. Let's analyze this composition. The photograph's focal point, the monstrance itself, stands rigidly upright. Two angelic figures flank the base. This structure creates a strong sense of symmetry, yet it is rendered through light and shadow with stark tonal contrast, typical of photography from this era. Note how the dove atop the monstrance becomes the culminating detail, a formal echo of its base. Editor: Absolutely, and seeing it documented within what appears to be a sketchbook is interesting too. Consider the colonial and post-colonial implications: were these exhibitions spaces of cultural celebration, or were they participating in the objectification and control of religious practices, transforming sacred objects into mere artifacts within a European narrative of progress and control? Who was the audience for this exhibition? What narratives were presented about the cultures from which these objects originated? Curator: That reading shifts our perception considerably. If we consider the photograph itself as an artifact—documenting another artifact that may itself be imbued with fraught histories— the angles create interesting vectors of meanings and interpretations! Editor: I think examining these questions pushes us beyond pure aesthetic appreciation, urging us to grapple with art's broader cultural and historical implications, even in the absence of all information related to provenance. Curator: Indeed. It reminds us that form and context are intrinsically linked, regardless of their source or origins. Both frame and reveal elements within a work of art, enhancing a sense of aesthetic consideration or offering the possibilities of an historic narrative.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.