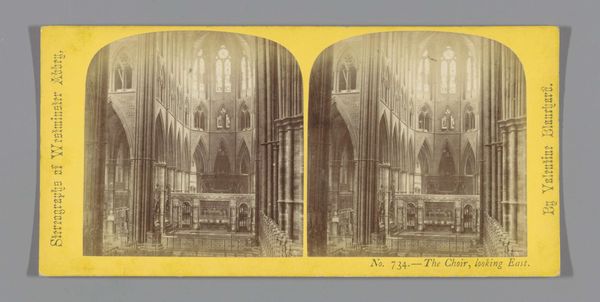

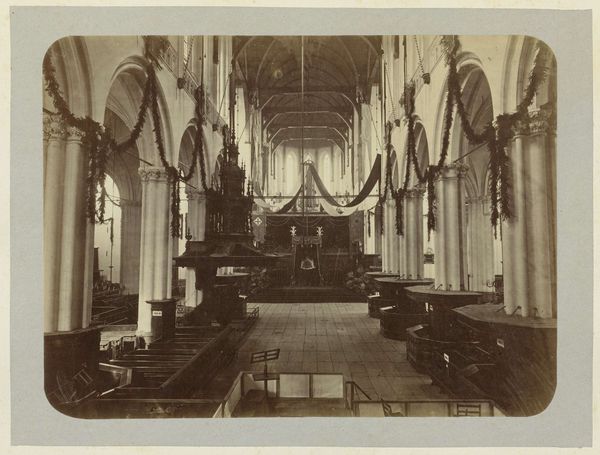

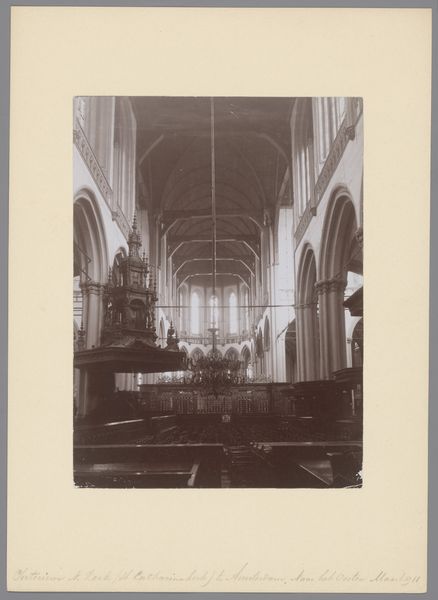

Gezicht op het interieur van de Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam 1860 - 1885

0:00

0:00

pieteroosterhuis

Rijksmuseum

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

perspective

#

photography

#

geometric

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 171 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Pieter Oosterhuis’s gelatin silver print, “Gezicht op het interieur van de Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam,” created sometime between 1860 and 1885. Editor: It feels so...stark. The monochrome palette coupled with the geometry of the interior creates this sense of quiet desolation. Are we sure there’s no one in there? Curator: It certainly emphasizes the architectural space. The New Church was historically a site of significant civic events, royal coronations, national celebrations. Photography at the time was still quite novel; Oosterhuis’s rendering situates this national monument in the growing visual culture. Editor: That's the tension for me: a sacred space becomes an object, consumed by a burgeoning visual culture and, well, *capital*. Churches held so much social power then, didn’t they? Births, marriages, deaths…all recorded and legitimised by the Church. The act of picturing the empty interior feels quietly radical. Curator: Well, photography also became essential for documenting and preserving cultural heritage. In many ways, it democratized access. You didn’t have to be physically present to engage with it, or rely solely on painting or engravings, for example. Editor: But who had access to the photographs? What was the societal reach? Were they distributed equally across different social strata? Those are critical questions for me. I wonder if its realism was intended as a kind of truth-telling or symbolic reclamation, given the fraught relationships between religious institutions and marginalized groups. Curator: Perhaps Oosterhuis was aiming to capture the sublime quality of the architecture itself, devoid of any specific event. This kind of interior view provided a tangible image for a growing urban population interested in their built environment. Editor: Fair enough. For me, it still raises interesting questions about the control and authority implied in documenting places of worship—and who ultimately benefits. But I appreciate its technical clarity—it's stunning, really. Curator: And that is precisely why its historical positioning is crucial, as it helps reveal societal shifts through artistic choices and technologies. Editor: It leaves us plenty to consider about space, power and perspective.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.