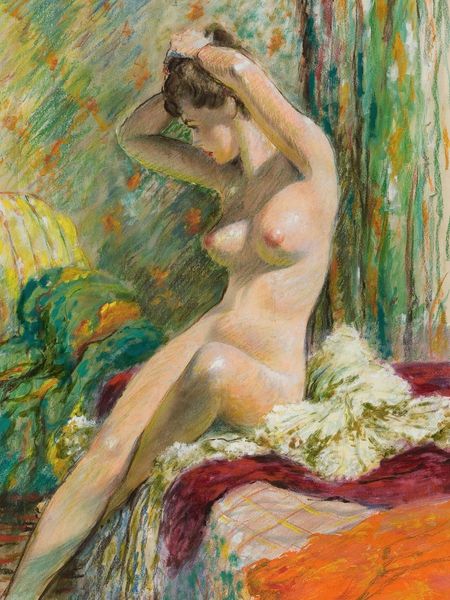

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

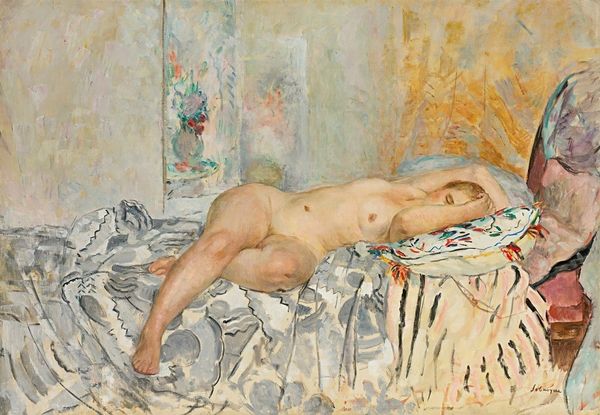

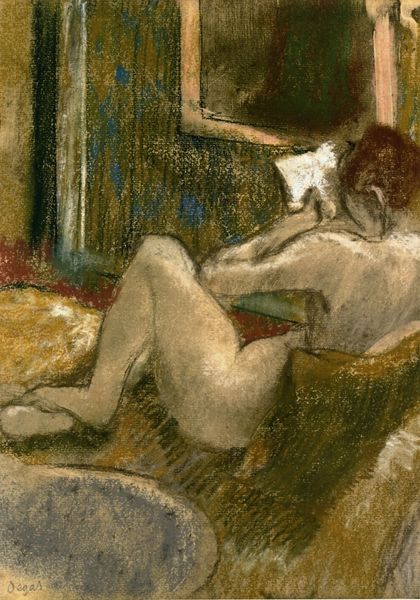

Editor: So, this is Henri Lebasque’s "Nu Assis," painted in 1936, using oil on canvas. There's a gentle, almost domestic feel to it. How do you interpret this work, especially given its historical context? Curator: That intimacy you sensed is key. Lebasque positions this nude not as an object, but within a space suggesting private contemplation. Consider 1936 – a world bracing for war. Does this intimate portrayal of the female form represent a retreat from or a subtle defiance against, the rising tides of fascism and its control over women's bodies? Editor: A defiance, maybe? I hadn't considered that. It's not overtly political, though. Curator: Exactly, its power lies in the subtle subversion. Instead of the idealized or eroticized nudes that dominated much of art history, here we see a woman simply *being*. She's not posed for the male gaze in the same way as more traditional nude paintings. The lack of overt sexuality feels significant. Do you think that adds to its quiet resistance? Editor: I do. It challenges the expected narrative. And thinking about Intimism, that makes sense, it’s not necessarily meant to be titillating or performative, but maybe something more mundane, which might have its own subversive charge. Curator: Precisely. Mundane can be revolutionary, particularly for women’s representation in art. By stripping away the performativity you mentioned, Lebasque potentially allows for a reading that emphasizes the woman's agency. What is her story in this moment, regardless of outside viewers and critics? Editor: I’m struck by how considering the sociopolitical climate deepens my appreciation for the work. It goes beyond the purely aesthetic. Curator: And that's the beautiful potential of art history – to see artworks as active participants in shaping, reflecting, and sometimes quietly resisting the world around them. Thank you, I see things differently now too!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.