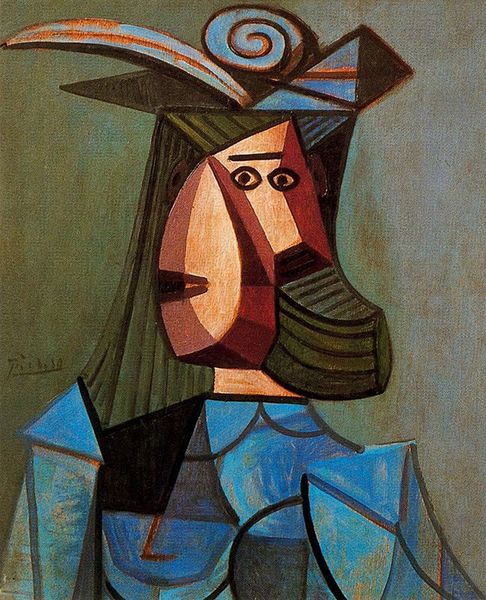

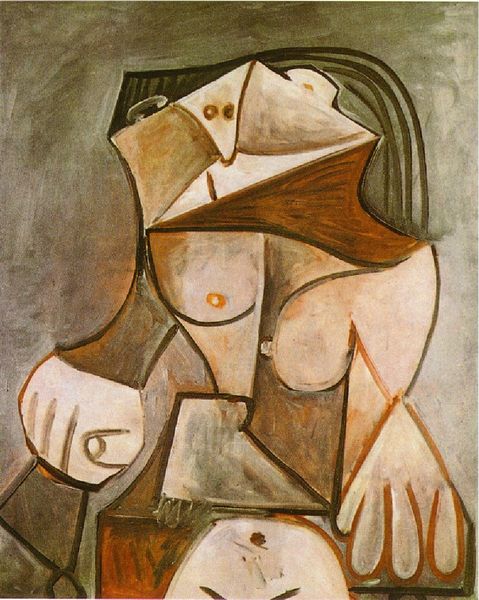

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

cubism

#

art-nouveau

#

abstract painting

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

geometric

#

abstraction

#

portrait art

#

modernism

Dimensions: 116 x 89.2 cm

Copyright: Public domain US

Curator: Pablo Picasso's "Cubist Person," painted in 1917, presents us with a striking exploration of form and identity. It's oil on canvas. Editor: My first thought is how earth-toned and abstracted the figure is. The use of ochres, umbers, and creams create a warm yet disorienting atmosphere, with its fragmented visage and elongated shapes. What exactly is Picasso trying to materialize here? Curator: I think it is rooted in interrogating representation itself. Consider the time. World War I was raging; old orders were collapsing, and the portrait, through the lens of cubism, captures a sense of fractured identity in response. The personhood here seems disassembled and reconfigured, which you know connects with wider modernist anxieties about self and society. Editor: Right. I see a very controlled, even craftsman-like approach to deconstruction, which has material implications for both artist and subject. The thick paint, those almost brutalist geometries; what labour went into reshaping, reimagining this individual? Curator: The labor aspect interests me greatly. What social circumstances enabled Picasso to abstract the sitter so radically? How might race, class, gender dynamics inform his particular rendering? His gaze, if we can call it that in this composition, is inherently tied to power relations and the objectification apparent within. Editor: Interesting. Objectification through abstraction is at play for sure. But, look at how deliberately Picasso builds his image using oil. It's not just conceptual dismantling, is it? It is a constructive act using materials in ways specific to early 20th-century capitalism; to commodify a portrait even as its legibility collapses—a paradox isn’t it? Curator: That's precisely the friction that keeps me returning to Picasso. How do we navigate the historical, social, and theoretical issues around representation while grappling with art market value, and commodification of labour? And furthermore, think about what social upheavals may emerge during and after wars, revolution, etc., with social commentary interwoven into artistic representation? Editor: This makes one think of a portrait in name, and maybe something deeper and unsettling. An interrogation that reveals not what is, but how its construction is material and how we can analyze that. Curator: Precisely, and situating that interrogation within historical and power contexts expands our viewing from aesthetic pleasure to engaged critical awareness. Editor: Agreed. Now that’s material.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.