photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

light coloured

#

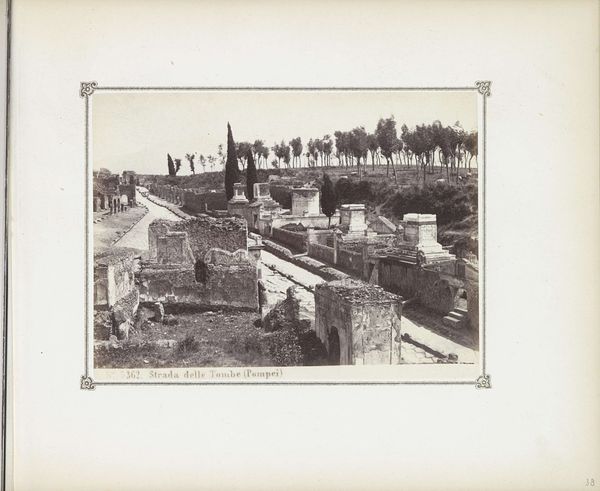

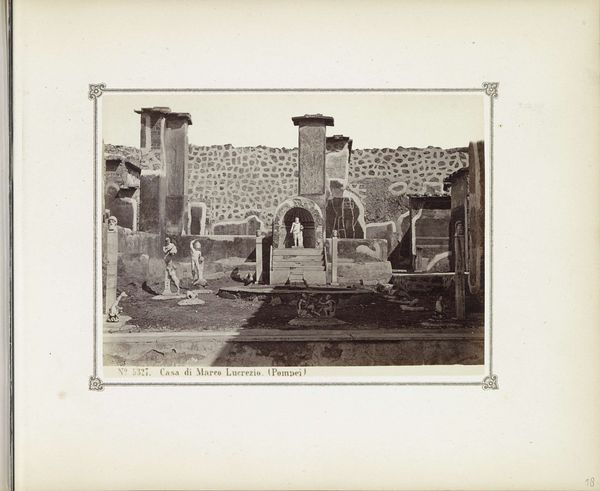

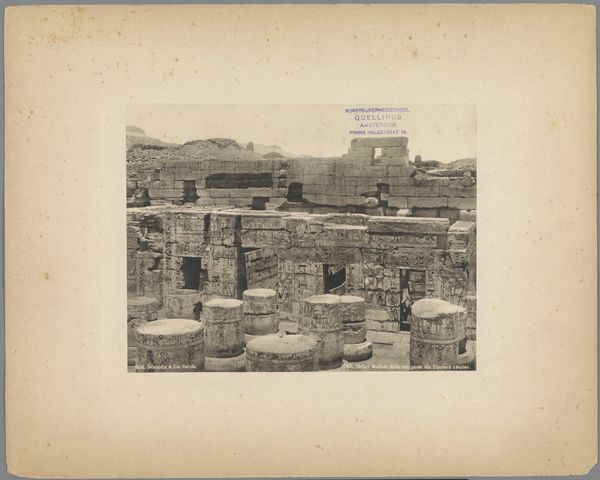

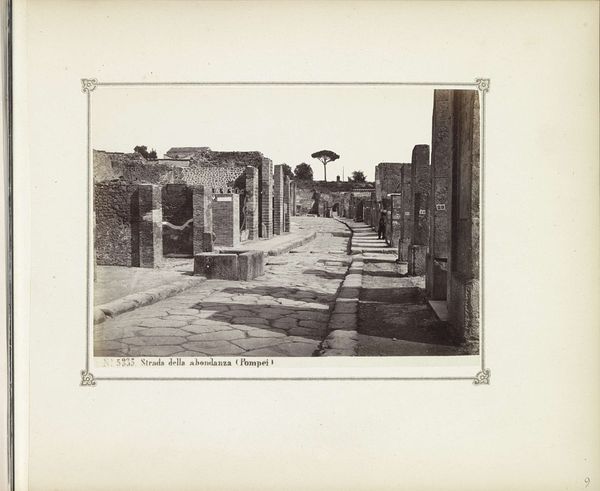

landscape

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

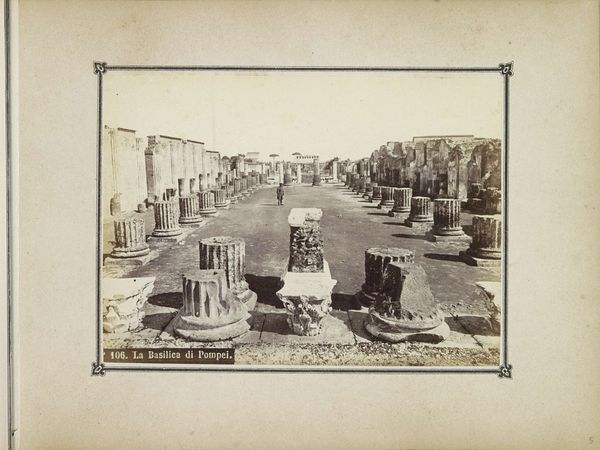

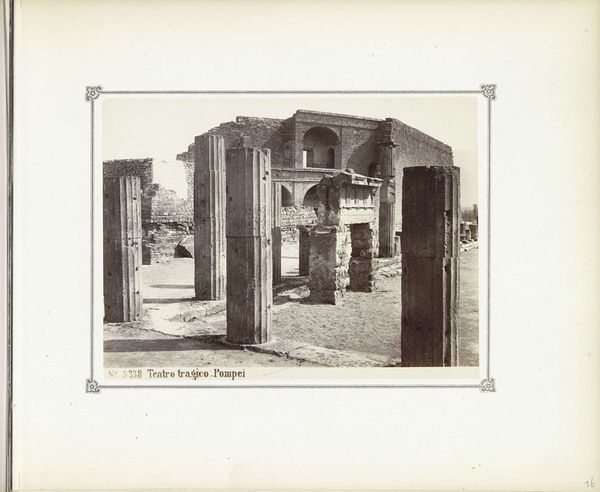

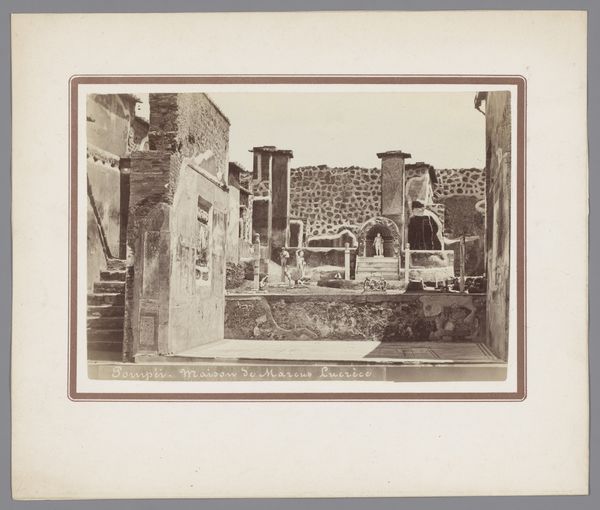

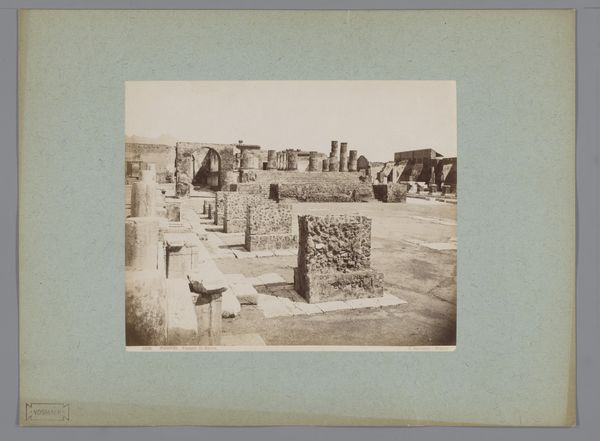

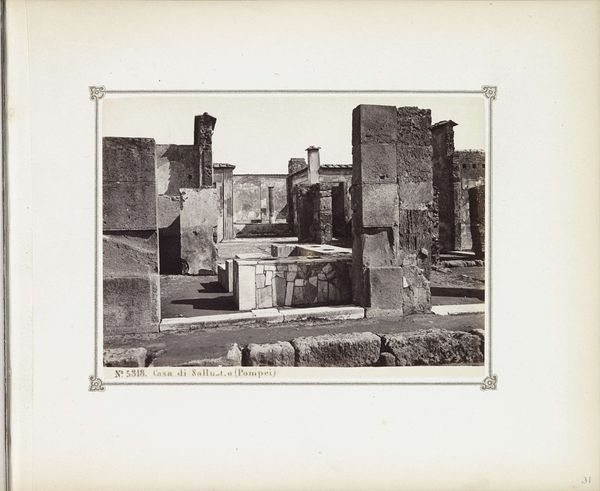

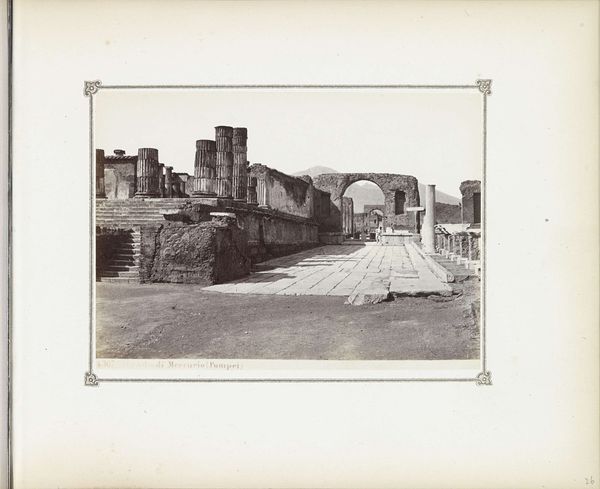

Dimensions: height 102 mm, width 139 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This photograph, a gelatin-silver print, captures "Restanten van het Huis van Diomedes in Pompeï," or, "Remains of the House of Diomedes in Pompeii." Giorgio Sommer likely created it sometime between 1860 and 1900. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: A hush falls over me looking at this. The straight lines of the colonnade in shadow against the bright sky... it’s almost melancholy, this documentation of loss. It's very striking to imagine a city frozen in time. Curator: The image itself is very much a product of its time. Photography in the late 19th century played a crucial role in archaeological documentation, shaping the way people understood and accessed these ancient sites. Sommer, in capturing the House of Diomedes, was participating in a larger movement to bring antiquity into the modern era. Editor: Right. And that sense of discovery and making the distant past touchable comes across strongly. But the artistic choice also really stands out, right? It’s not a purely objective record; Sommer chose the angle, the light, how much sky to include… there is a story being built here. It makes me wonder about the ethics of witnessing, really. Are we tourists to someone else’s tragedy even now, centuries later? Curator: It’s definitely a negotiation, isn't it? Between science, aesthetics and our relationship to this city’s trauma. The light and shadow play is purposeful here and can serve to remind people of the story, one mostly known from Pliny the Younger. Sommer has offered not just ruins but a stage where our imaginations might explore and relive this history. These images really offered mass audiences an almost intimate peek at antiquity in ways that engravings could not offer. It's the reason such photographs and the photographer became sought after in tourist markets as well. Editor: Ultimately it gets to why this photograph speaks to us now, doesn’t it? That intersection of beauty and ruin. Thanks for sharing this history, I had not previously thought so deeply about the act of historical image making and its complex relationship with our experience. Curator: Likewise. I think looking at photographs of Pompeii urges one to consider the role and impact of these images throughout the later 19th century until now. It gives pause to one's viewing experience.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.