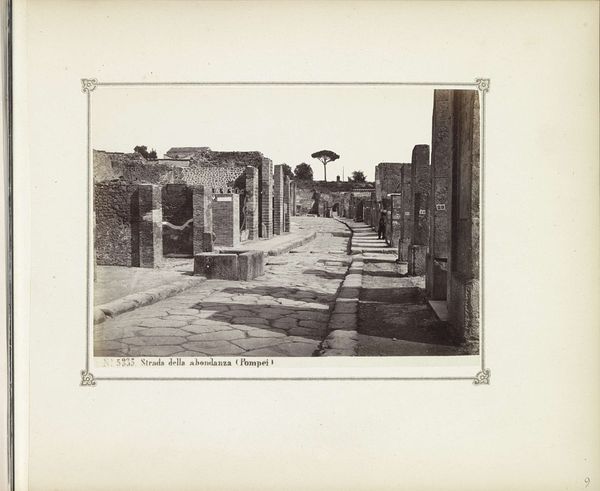

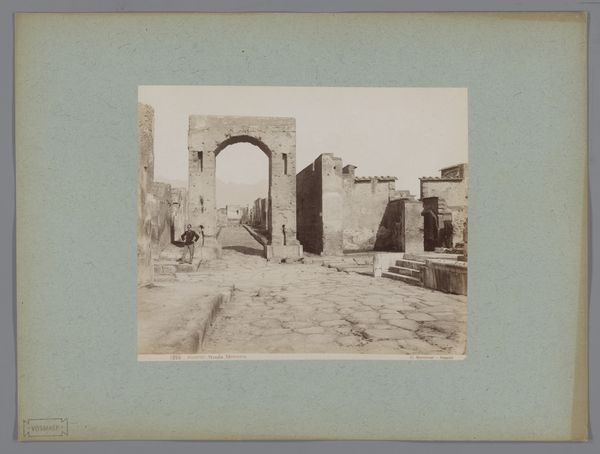

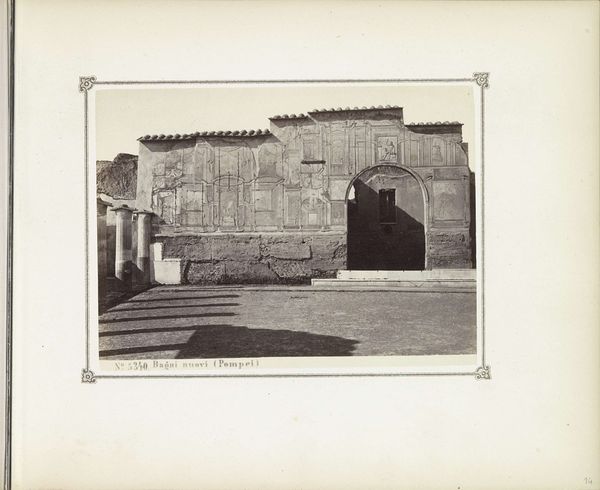

Restanten van gebouwen aan de Via di Mercurio in Pompeï c. 1860 - 1900

0:00

0:00

giorgiosommer

Rijksmuseum

photography, photomontage, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

photomontage

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

street

Dimensions: height 102 mm, width 142 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s discuss this photograph, “Restanten van gebouwen aan de Via di Mercurio in Pompeï,” a gelatin-silver print from circa 1860 to 1900 by Giorgio Sommer, here at the Rijksmuseum. The remnants of buildings line a street in Pompeii. Editor: There's a palpable sense of absence in this image. The ruins against the bright sky feel ghostly, the silence almost deafening. Curator: Sommer’s photograph freezes a moment of rediscovery, yet it also embodies a longer history. Consider the labor that extracted these materials, the societal structures that defined ancient Roman urban planning, the volcanic eruption—how power, nature, and human life were abruptly interrupted. Editor: It makes me think about the act of photographic documentation itself, framing and capturing these materials to bring Pompeii to European society. The image, a gelatin silver print, it is a carefully composed tableau, made with skilled labor for consumption as knowledge, leisure. I wonder how many prints were made of this scene. Curator: The city’s destruction and subsequent excavation is a violent intrusion on daily life, now turned spectacle, or documentation for academic interest. Its resurrection offers a stark parallel to how historical narratives can reinforce societal structures by choosing who gets to be remembered, who is excluded, and for what reason. Editor: Right, the selection, the framing! Even down to the specific choice of chemical process. Photography emerged in lockstep with industrial production and archaeology's development as a formal discipline. This photograph has many things to tell us about its contemporary moment too. Curator: And who gets to tell that story matters. Consider the gendered roles in archaeology at that time, the class distinctions of who funded excavations, the implications of depicting a colonized space, all contributing to this "objective" record. Editor: It's a good reminder of how something that looks still is dynamic, it involves labour and time. Curator: I agree. It pushes me to contemplate history's complex layers. Editor: Absolutely. It pushes us to consider the lives erased in history as much as the monumental structures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.