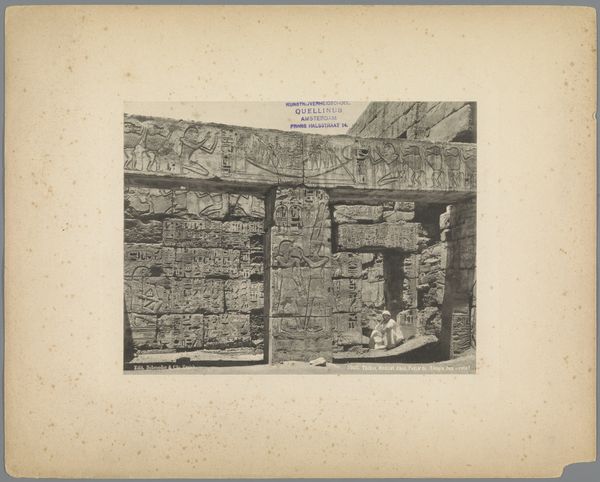

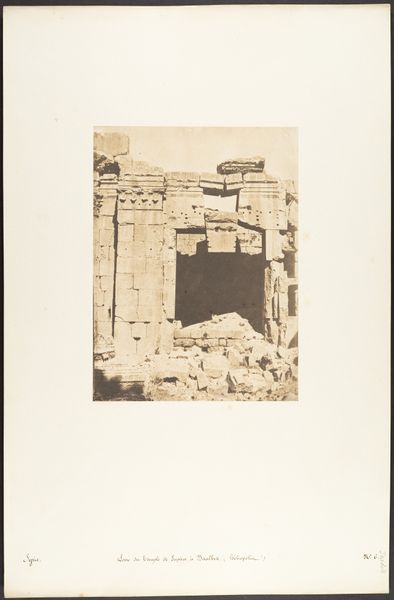

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

column

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 209 mm, width 272 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

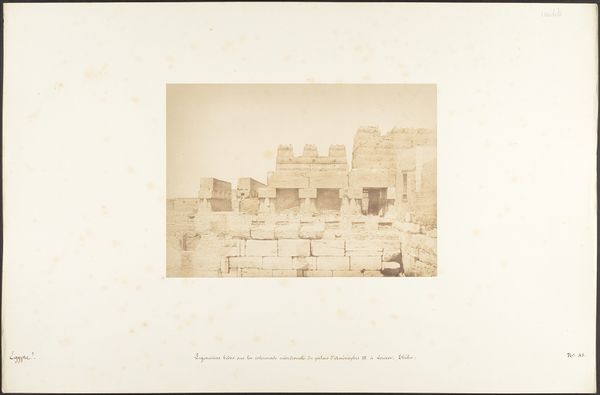

Curator: This gelatin-silver print captures what remains of the columns in the temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu, and it was produced circa 1875-1900. It's unsigned, placing it in an interesting position, origin wise. Editor: The scale is instantly arresting; the ruins convey such a potent sense of the past through light and shadow. There's a tactile quality to the weathered stone; one can imagine running their hand over those hieroglyphs. Curator: Precisely! Observe the columns—the surviving reliefs invite a semiotic reading, perhaps clues to understanding the temple’s purpose and Ramses' reign through coded inscriptions. What processes and labour might these images suggest, though? Editor: Immense ones, I would wager. The sheer quantity of worked stone suggests vast organised labor—a whole society mobilised around quarrying, transport, carving… Consider the socio-economic forces necessary to produce such monumental structures; these images aren’t just pretty pictures, but they also invite speculations of how the ancient artisans understood production, what meaning these building enterprises carried within that society and to those specific laborers. Curator: Agreed, yet one mustn't neglect the aesthetic impact. Note how the anonymous photographer has composed the scene—the arrangement of pillars guiding our eye, constructing a dialogue between architectural remnants and negative space to invite contemplation of mortality and grandeur. This isn't just documentation; it is a narrative frame imposed on the original builders’ own symbolic lexicon, filtered twice over by an author-less hand and current viewing, shifting it towards something uncanny and removed from that ancient production entirely. Editor: The photographer is another link in that labor chain you suggested! Consider what camera, process, and the gelatin-silver medium entails. From a certain angle, each gelatin silver print echoes something of a material relation to stone work. So what relations might such works have with labor relations today? What value are we constructing in looking at it? Curator: Interesting! It is an index—of a cultural encounter, if nothing else. It’s clear that our interpretations are inevitably bound to the intrinsic materiality of these art objects as well as being filtered through layers of historical distance and modes of analysis. Editor: Precisely. I would suggest future studies to attend closely to the material processes and circumstances that inform ancient artisans alongside those that inform later modern cultural reproduction, even when their relation may not be visually evident in the work itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.