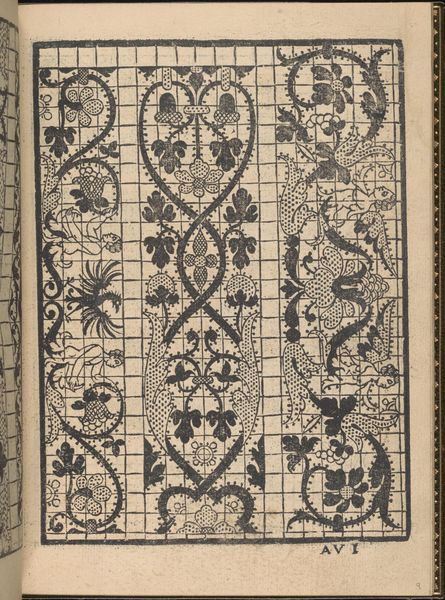

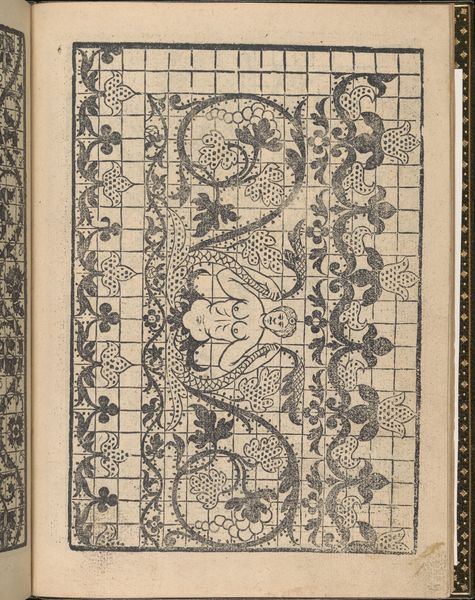

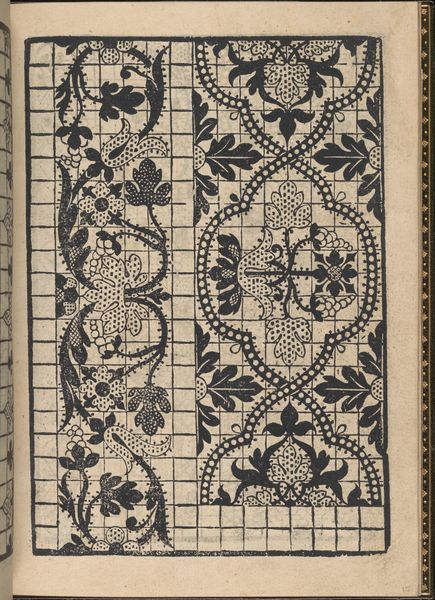

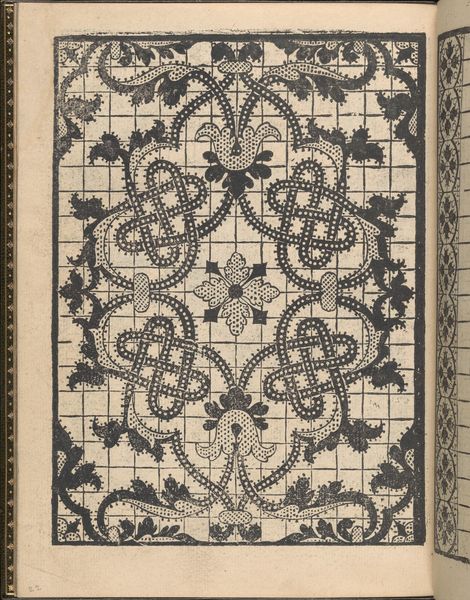

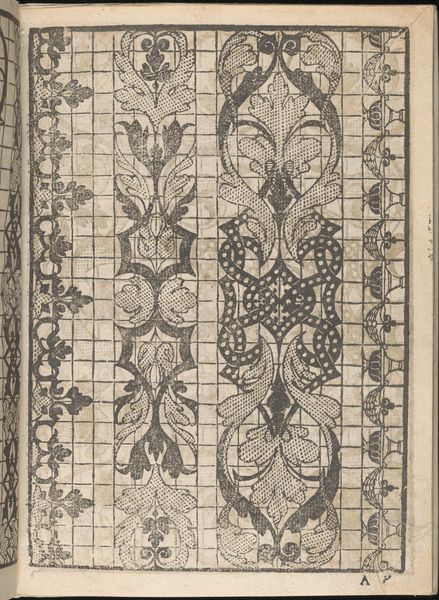

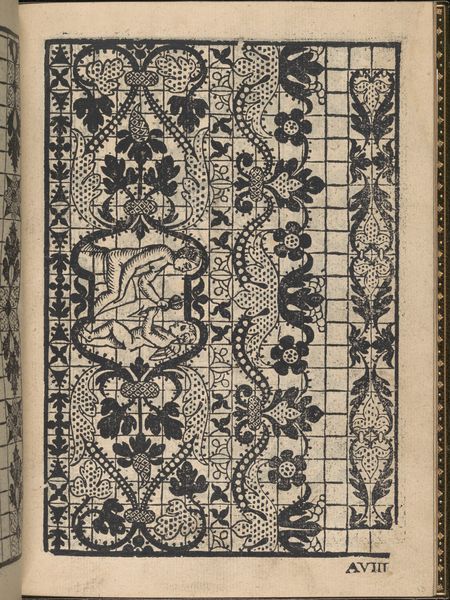

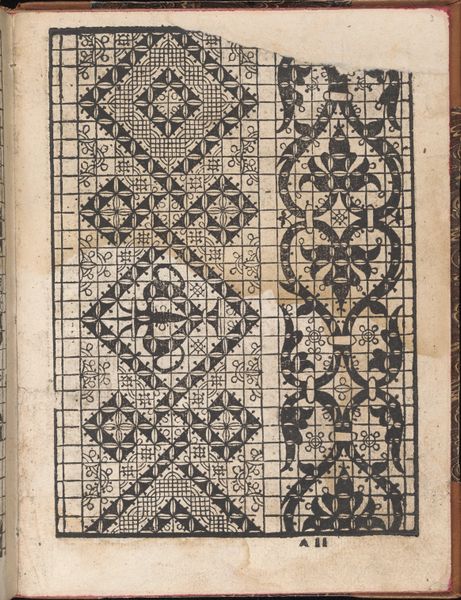

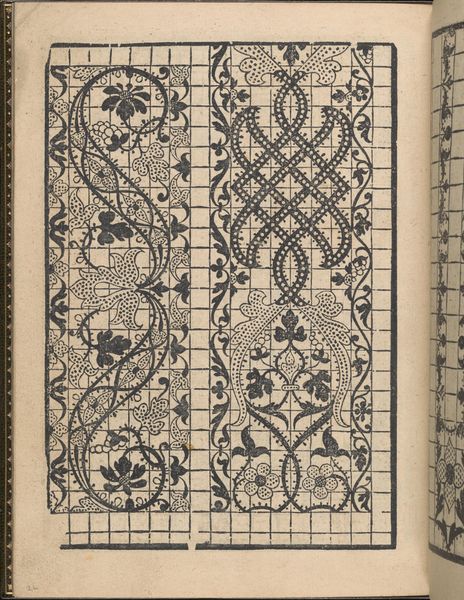

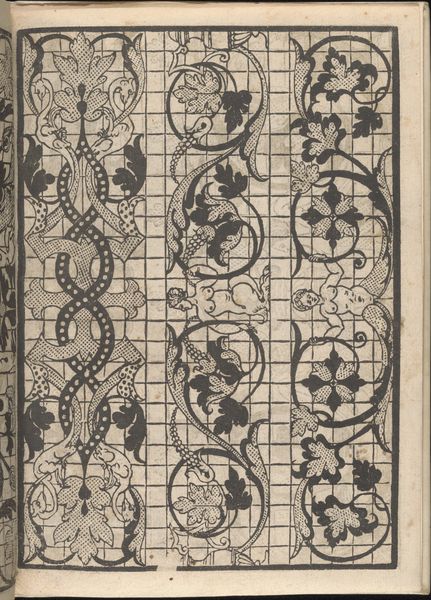

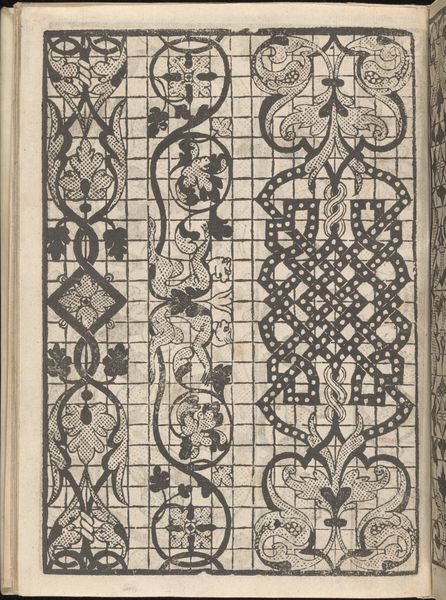

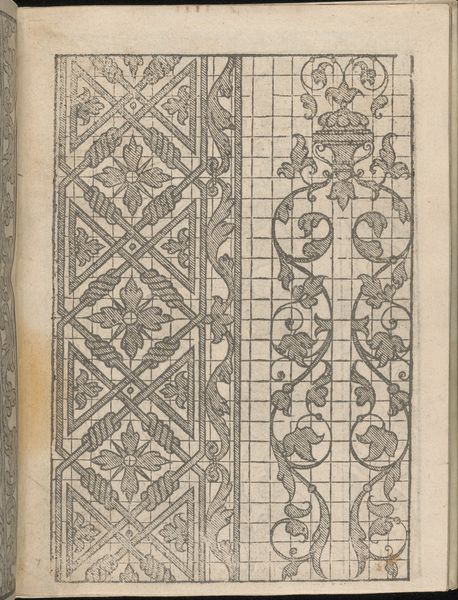

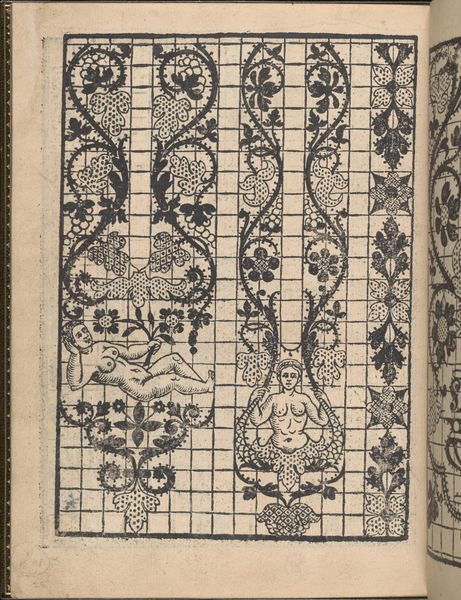

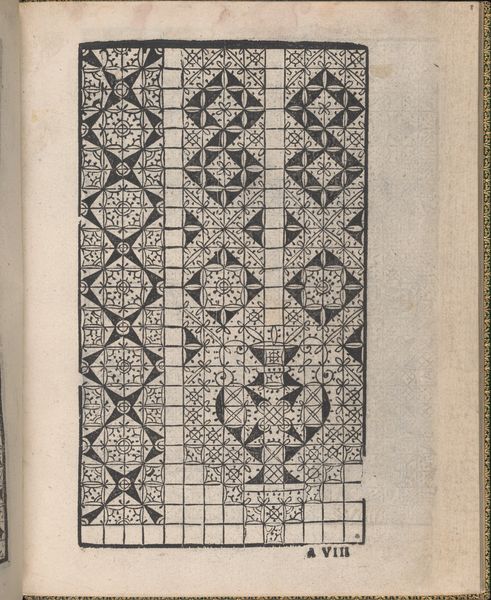

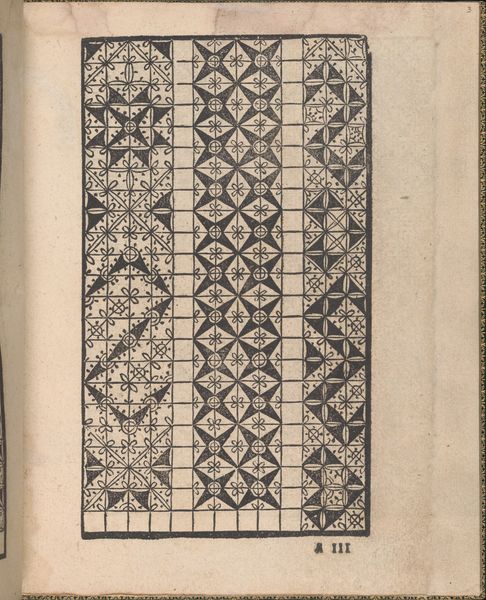

La Gloria et l'Honore di Ponti Tagliati, E Ponti in Aere, page 3 (recto) 1556

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

pen drawing

# print

#

book

#

11_renaissance

#

geometric

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: Overall: 8 1/4 x 6 1/8 in. (21 x 15.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: What an intricate page. This is *La Gloria et l'Honore di Ponti Tagliati, E Ponti in Aere, page 3 (recto)* by Matteo Pagano, dating back to 1556. It’s currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It's an engraving, likely part of a book of designs. My initial impression is one of rigid structure punctuated by organic motifs. Editor: Yes, a fascinating tension, isn’t it? Immediately, the grid leaps out, suggesting constraints, order, and perhaps even societal expectations. The title talks about "bridges" cut or hanging "in the air"— suggesting a tearing down or dissolving of structural frameworks. Do you read it that way, a kind of defiance or perhaps a yearning for liberation from those set boundaries? Curator: Absolutely, I read a challenge within the established social order. Notice how the floral patterns, with their associated concepts of beauty and fragility, are superimposed on this harsh grid. It is not a passive decoration. Consider how the grape clusters may hint at feasting, abundance, a more luxurious existence. They become almost a subversive act. And as women have historically been associated with both "beauty" and "fragility," one cannot avoid interpreting the floral work on the geometric structures as representative of social struggles of its period. Editor: I agree. There is a compelling opposition here. To dig into these symbols further, what’s powerful about grapes is their link with celebration, harvest, Dionysus. But their positioning at certain intersections suggests strategic disruption, little acts of rebellion if you like, planted intentionally. Also, the dot pattern seems deliberate as it reinforces but also disrupts the grid. It may represent a call and response between tradition and something new. Curator: Right, the subtle alteration. It calls for closer study. We cannot consider design elements removed from socio-cultural and gender expectations or anxieties during the Italian Renaissance. What does it mean to "glorify" such structural breaks, especially when the role of women in public life was quite prescribed? Editor: A beautiful contradiction— the very act of "glorying" these acts subverts the conventional narratives. It could suggest a silent, persistent strength inherent in elements that may appear fragile but actually weave the seeds of reform. I shall definitely look more closely at how the floral symbols disrupt geometric rigidity. Curator: Yes. Perhaps the bridges do not just break, but grow.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.