print, intaglio, engraving

#

portrait

#

self-portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

intaglio

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 207 mm, width 147 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

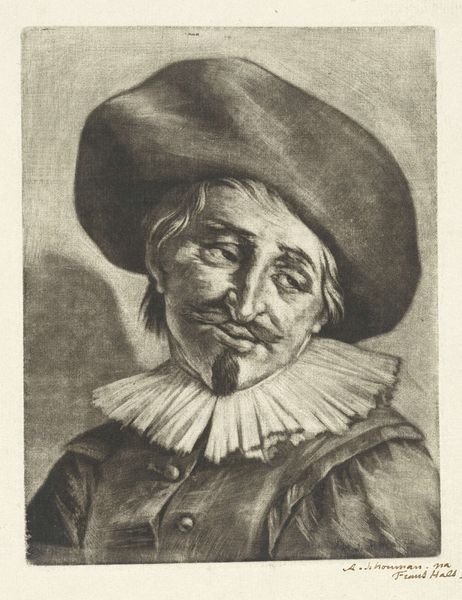

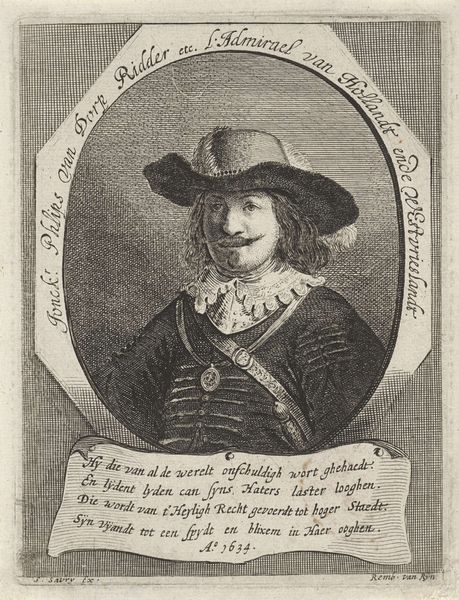

Curator: Looking at "Man with a Miniature Portrait in His Hand," dating roughly from 1615 to 1676 and attributed to Theodor Matham, the immediate impact is that of playful intimacy. It’s currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. What's your take on it? Editor: There's a strong sense of self-awareness emanating from the subject. The miniature portrait in his hand and even the smaller portrait attached to his feathered hat create almost an echo-effect; the man clearly has some story to tell about love or attachment that is visually quite compelling. Curator: Indeed. I think Matham offers a very public expression of personal feeling through these reproduced portraits. This was a period where access to likenesses of people became democratized through prints. Portraits start circulating. So how do these new technologies shift expressions of affection in Matham's era? Editor: Miniatures were significant status symbols and deeply personal tokens of affection. To publicly display these small likenesses meant something beyond the mere representation of wealth, something touching upon personal psychology and self-identity tied up within loved ones. I’m particularly intrigued by the portrait miniature attached to his hat feather—a seemingly frivolous addition that transforms the item from practical wear to ostentatious announcement. Curator: This form of display had political implications, of course, demonstrating who one favored in public society. The distribution of portrait prints allowed broader access to those in power, impacting perceptions of leadership. Beyond the personal, prints functioned to engage subjects with figures and ideas that influenced political debate. Editor: It highlights that people use images and their reproduction in complex ways to display devotion, personal taste, and even project power. In my view, it anticipates modern concepts of self-branding, demonstrating how images, especially portraits, act as extensions of one’s persona. This particular piece speaks to a timeless aspect of the human condition. Curator: Yes, the commodification of portraiture helped people align themselves to influential or political communities. I hadn't considered that modern self-branding implication, but that definitely opens another path for considering its continuing significance. Editor: And so we move from images of power to self-empowering images.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.