An Anatomical Lecture at Royal Academy of Arts c. 1780s

0:00

0:00

drawing, watercolor, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

watercolor

#

ink

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 8 1/4 x 11 in. (20.96 x 27.94 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

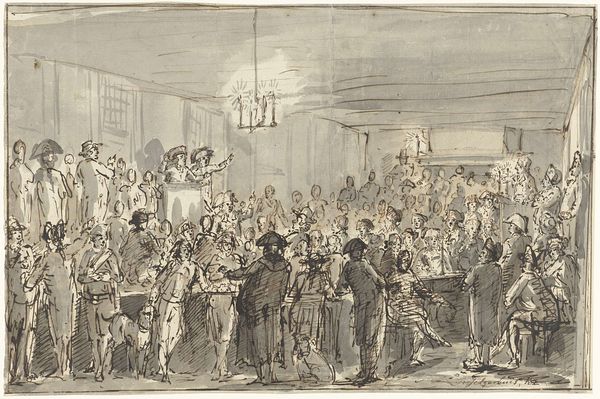

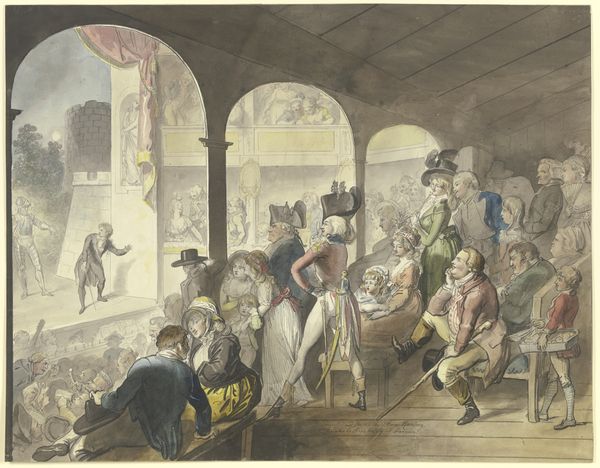

Curator: So, here we have Thomas Rowlandson's "An Anatomical Lecture at Royal Academy of Arts", an ink and watercolor drawing from around the 1780s. It’s currently housed here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. What's your immediate take on this scene? Editor: Well, it's rather macabre, isn't it? A sea of pale faces, all seemingly captivated by…death? The color palette feels a bit morbid, like a faded memory. Curator: Absolutely. Rowlandson had this wicked knack for capturing the grotesque side of Georgian society. He wasn't just drawing a lecture; he was holding up a mirror to his audience, skeletons and all, both literal and figurative, wouldn’t you agree? Editor: Agreed. The skull in the lecturer’s hand speaks volumes – a Vanitas symbol reminding everyone, perhaps a tad dramatically, of their own mortality. The classical sculptures behind the lecturer amplify this theme, a stark juxtaposition of idealized beauty with the crude reality of human anatomy. It all smacks of "memento mori", don’t you think? Curator: Precisely. There's that constant dance between life and death, isn’t it? But also look at the crowd. They are almost cartoonishly engaged. To me it underscores an eagerness, perhaps to get to the essence of human experience. What is beautiful? Where do the limits of our bodies lie? It's almost humorous. What are you drawing there in your sketchbook? Editor: A man in the audience who seems much more interested in his tankard than the lecturer's grim demonstration. It feels like a satire – not just of anatomy lessons, but of intellectual pretensions of the Royal Academy itself. Rowlandson seems to suggest that underneath all the enlightenment pursuit of knowledge, the base, earthly desires continue unabated. Curator: Spot on! There’s a sort of organized chaos. It's academic, yes, but alive, kicking, and totally unfiltered. One thing about ink and watercolor, you either commit to it or you don’t! The lightness of the touch keeps this heavy theme so fluid and alive, even if it has death staring us right in the face. Editor: True! It is quite stunning how the transparency of the medium actually brightens a dark subject. I see it as a symbol for our ability to reflect on tough and difficult concepts while living a vital life. Curator: In conclusion, what begins as an educational display reveals the depths of a cultural symbol still relevant to this day. Editor: Absolutely. In a single image we see human nature and an ironic critique of society's attempt to control that nature!

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

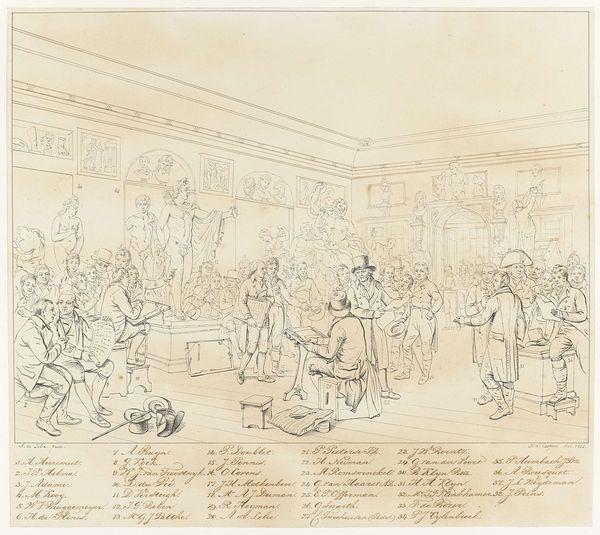

Rowlandson was a brilliant draftsman, producing complex, comical scenes with rapid, scrolling pen work. Here he represents an anatomy lesson at the Royal Academy of Arts in London where he had studied beginning in 1772 and exhibited works into the 1780s. The background statues and paintings identify the location. The lecturer is most likely Doctor William Hunter, a professor of anatomy at the academy. Rowlandson often poked fun at the sinister side of anatomical studies and dissection, and here he depicts Hunter with an odd grin on his face as he holds a human skull. Next to the doctor is displayed a skeleton of an improbable four-legged creature, a detail that further undermines the seriousness of his lecture. From a scribbled sea of faces, individual figures emerge in the audience, perhaps caricatures of fellow academicians. Their various reactions are masterfully catalogued-fascination, disgust, confusion, smugness, disinterest, boredom. The figure wearing a hat and holding an ear trumpet is probably the partially deaf president of the academy, Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.