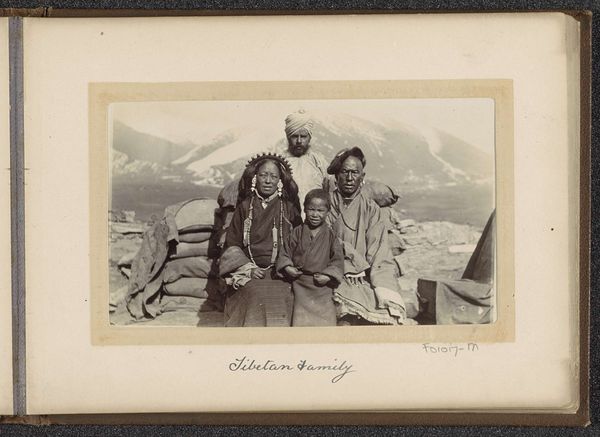

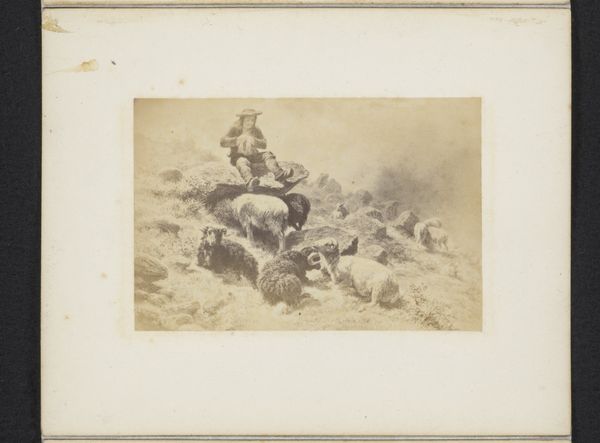

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

landscape

#

photography

#

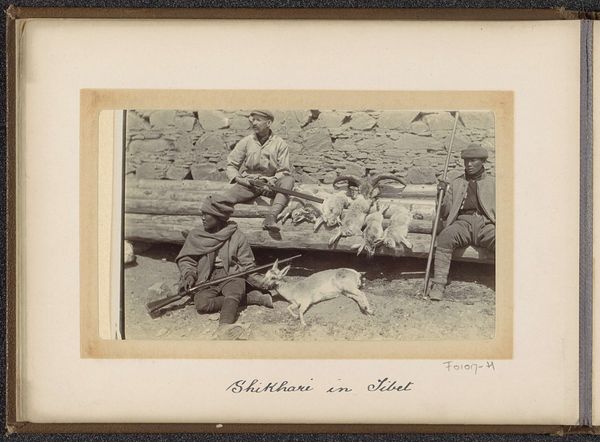

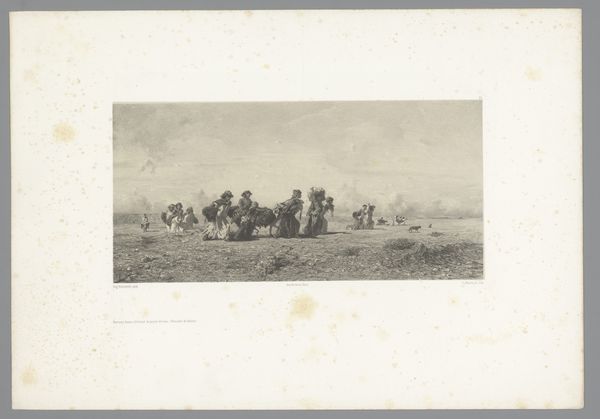

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 137 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

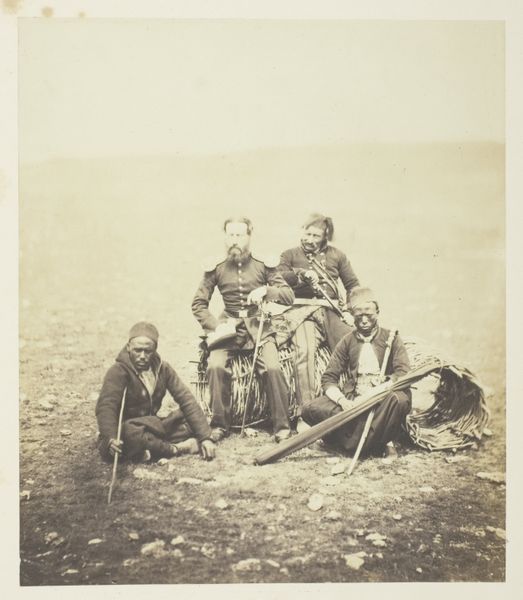

Editor: This photograph, entitled "Groep Tibetaanse dragers" by D.T. Dalton, dates from around 1903-1906 and is a gelatin silver print. I find the texture really striking, from the rocky outcrop they're sitting on to the seemingly roughspun clothes. What draws your attention to this piece? Curator: What I find fascinating is the very act of *making* this image. Think about the materiality: the silver, the gelatin, the chemical processes required. It speaks volumes about the industrialized world’s reach into even remote locales. How do you see the image production influencing the image itself? Editor: I hadn’t considered that! It almost feels…invasive. These men, presumably laborers, are posed formally. Was that common? Curator: The formal pose, coupled with the very *medium* of photography, suggests an effort to categorize and document. Who was commissioning this work? And what was its intended purpose? Knowing the context helps expose power structures inherent in photographic production. Who had the power to depict, and who was depicted? It's not a neutral act, it's a power relation played out through materials and processes. Does the title provided feel problematic? Editor: The inscription "Tibetan Coolies" definitely sounds... dehumanizing today. The term "coolie" itself is loaded. Curator: Exactly. That language underscores how these individuals were viewed – as expendable labor, a raw material in the colonial project. Understanding the image’s production and circulation within a capitalist framework is essential. How do you think knowing that informs our view today? Editor: I see what you mean. By looking at the materials and the context, it transforms from a simple portrait into a statement about labor, power, and the consumption of images themselves. Thanks. I'll definitely think differently about photography now. Curator: And perhaps consider whose stories the materials *aren't* telling. The absences can be as telling as the presences.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.