Dimensions: height 314 mm, width 449 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

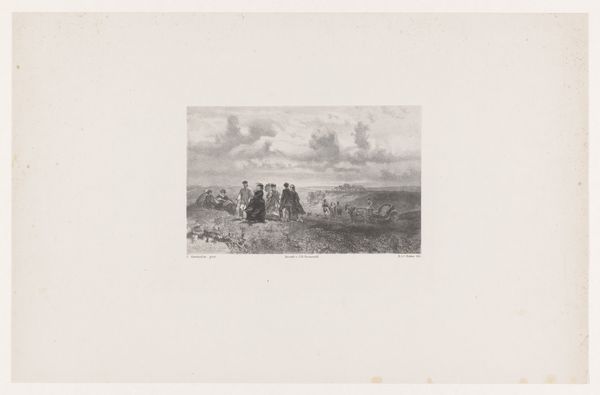

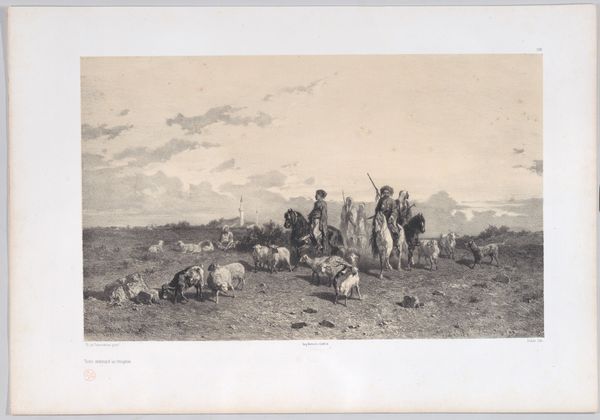

Curator: This evocative drawing, entitled "Vrouwen in de Sahara op terugtocht van waterput" or "Women in the Sahara Returning from the Well," created sometime between 1848 and 1862 by Célestin Nanteuil, immediately strikes me as quite desolate. Editor: The muted tones certainly contribute to that impression. Note the horizon line—it's placed incredibly high, dwarfing the figures beneath an immense, almost oppressive sky. There's a palpable imbalance in the composition itself. Curator: The labour involved is key here: water scarcity as a human-made disaster impacting those burdened to find it, mostly women. This drawing provides insight into the social structure of labour, doesn’t it? Editor: It does. Focusing purely on form, however, consider how Nanteuil uses pencil strokes to delineate figures versus background. Notice how detail diminishes with distance, almost dissolving into the sandy ground. Curator: True, it creates depth. But I’m drawn to how these women collectively transport this essential resource. Water in such dry environments represented life itself and, here, we can witness the communal labor required to attain this critical necessity. It’s the distribution of power within this collective effort that captivates me most. Editor: And the contrast is powerful. The delicate rendering of the women and children against the vast, stark emptiness heightens their vulnerability. Even the presence of the animals adds a layer of dependency and resilience, but how is Nanteuil asking us to decode all this using solely visual tools? Curator: Beyond aesthetics, Nanteuil is compelling viewers to acknowledge the exploitation associated with natural resources—especially, if this piece depicts the human cost involved in this geographical landscape, perhaps, even implicitly referencing the historical impact on people from colonial activities during the period of production? Editor: That’s a valuable socio-historical frame. Yet, perhaps by stepping back, beyond what’s visibly represented, the drawing’s strength lies in its raw expression and expertly composed image itself; the composition creates space for reflection. Curator: Yes, while aesthetic consideration is vital, considering the social production also unearths so much meaning. Editor: Indeed, it does provide a crucial cultural and social insight that you cannot achieve simply by observation alone.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.