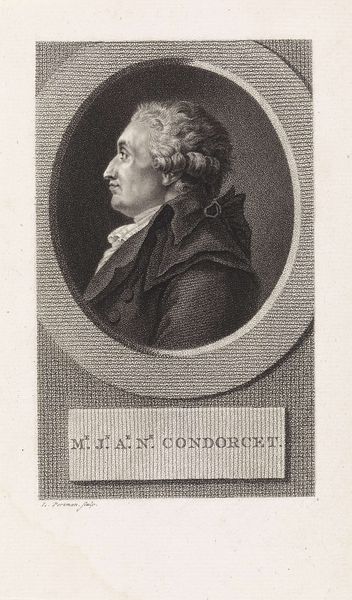

engraving

#

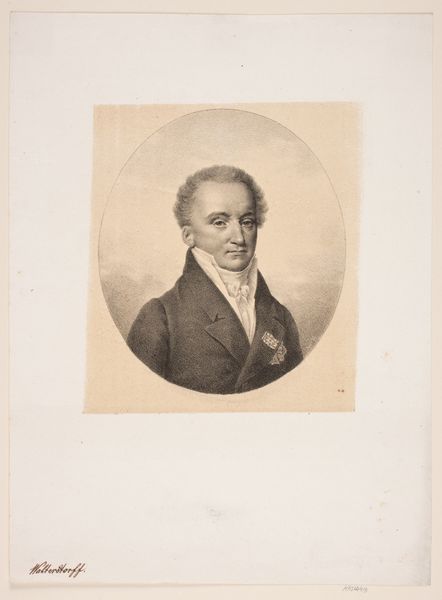

portrait

#

baroque

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 257 mm, width 174 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a portrait of Pieter Schenk, made sometime between 1680 and 1713. It's an engraving, and I find the formal composition of the oval frame around the subject adds to its slightly stern, official feeling. How do you interpret this work? Curator: What strikes me is the statement “Sculptor Amsteladamensis”. Placing that phrase so prominently below Schenk is an assertion of artistic and civic identity. What does it mean for Schenk to have his profession and place so assertively tied together for the audience of this print? Editor: I hadn’t considered the political implications. It's like saying, "I, Pieter Schenk, am a *leading* sculptor *of* Amsterdam!" Was there some incentive for artists to be associated with particular cities? Curator: Absolutely. Amsterdam was a thriving hub, and artists gained prestige and patronage by associating themselves with the city’s cultural clout. But I think we should also consider who was commissioning these engravings and where they were being distributed. Were they used to promote Schenk, the city, or both? Editor: So the portrait itself serves almost as an advertisement, broadcasting Amsterdam’s artistic prowess to the world. Were these types of artist portraits common at this time? Curator: Very much so! It's a moment where the image, the profession, and the place all worked together to build cultural capital, not just for Schenk but for Amsterdam itself. These portraits helped to craft an idea of a culturally rich and powerful city, solidifying its position in the European landscape. Editor: Fascinating! I always thought of portraits as individual commemorations, but this gives me a much wider perspective on their cultural and even political function. Thank you! Curator: My pleasure. Seeing art as part of the larger cultural and political landscape truly changes everything.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.