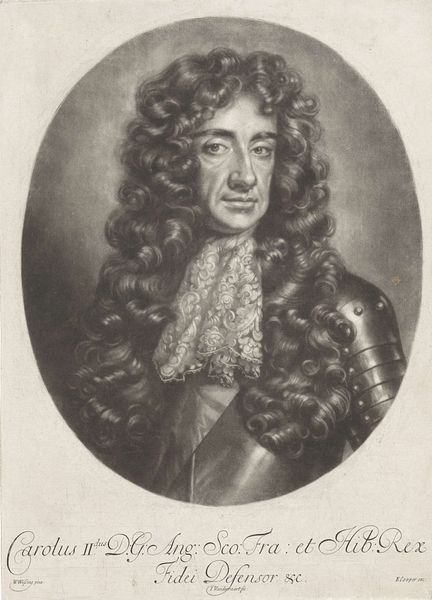

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 141 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a print dating from between 1662 and 1726, found here in the Rijksmuseum. It’s entitled “Portret van Sir Peter Lely,” and it was created by Gerard Valck. Editor: My immediate thought is: that's a lot of wig! I mean, the volume alone suggests wealth and status, but there's also something theatrical about it, wouldn’t you agree? Curator: Absolutely. Hair, particularly elaborate wigs like this, served as powerful symbols of social standing. Beyond mere fashion, it represented adherence to a certain cultural script, a visible marker of belonging to the elite. Consider, too, how meticulously it is rendered in the engraving! Each curl, each shadow painstakingly etched. Editor: Right, it's a Baroque aesthetic turned up to eleven. It speaks to a time obsessed with outward appearance reflecting inner qualities, whether real or performative. This portrait begs the question of accessibility, because only those of means would own something like this print, while simultaneously promoting the idea that wealth leads directly into respect. Curator: That contrast interests me, too. Lely was himself an artist, favored among the court of Charles II. He came to represent a specific style of British portraiture. Valck, in creating this engraving, makes it an artifact to be circulated and viewed, embedding Lely in a broader cultural narrative of artistic prestige. I find a distinct and powerful symbolic weight here, which creates visual memory that exceeds pure documentation. Editor: I see what you mean about a deliberate construction of the artist as icon. But I can't help thinking of how that "prestige" relied on very specific, often exclusionary social structures. Consider who *didn’t* get their portrait engraved during this time, the lives and histories deemed unimportant. Still, it has lasting appeal today: Lely's piercing eyes draw me in. The meticulous detail of the lace collar. There's a palpable humanity beneath the surface of the image. Curator: It does humanize Lely, but it does something else for British culture as a whole by establishing an ethos for artists which has endured through centuries. This one artifact in a collection can start meaningful discussion, don’t you agree? Editor: Exactly! I can't leave here without re-thinking my place within structures which elevated people like Lely to positions of reverence within an art historical canon.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.