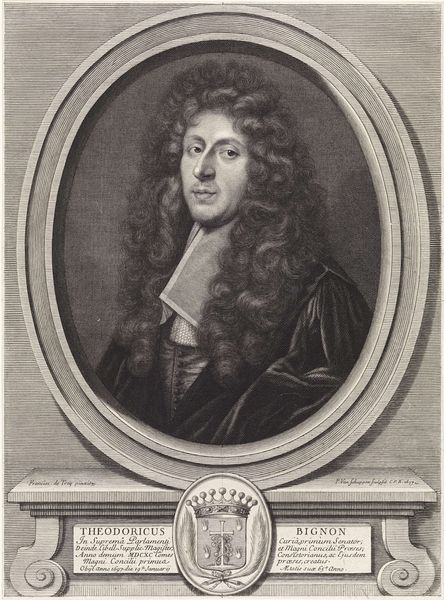

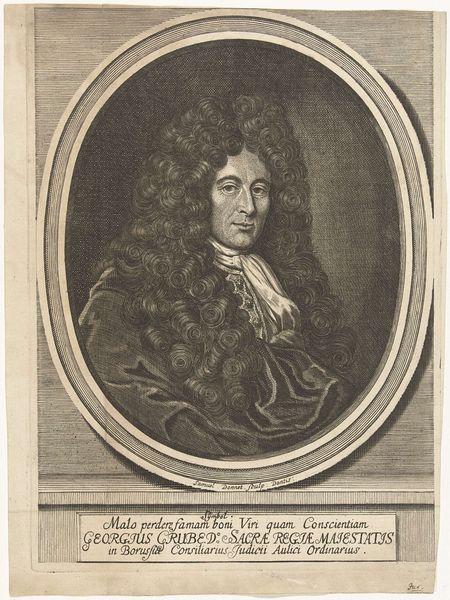

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

engraving

#

columned text

Dimensions: height 242 mm, width 190 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Take a moment to examine this remarkable engraving at the Rijksmuseum. It’s a portrait of Jean-Baptiste de La Quintinie, attributed to Gérard Edelinck, and believed to have been created sometime between 1666 and 1707. Editor: It’s… intense. The level of detail is striking, especially in the hair and the texture of the fabric. There’s a real weightiness to the image, despite it being a print. Curator: Indeed. La Quintinie was no ordinary subject. He served as the director of all the fruit and vegetable gardens of King Louis XIV. So, this portrait speaks volumes about the role of agriculture and horticulture in 17th-century French courtly life. Editor: The oval frame…and the coat of arms. The curls upon curls seem to symbolize a… cultivated abundance, reflecting his position, but perhaps also hinting at an almost overwhelming opulence. The image definitely says “status”. Curator: The imagery and presentation, precisely! The engraver, Edelinck, was highly sought after and demonstrates the political function of art; even this seemingly straightforward portrait worked to uphold the power of the French monarchy by showcasing its influential figures. Editor: And there's a kind of contained wildness too, isn't there? Even in the controlled setting of a royal garden, or within the sharp lines of an engraving, nature – and perhaps human nature – strives for the baroque flourish. Curator: Absolutely, and that interplay between control and exuberance mirrors the broader dynamics of the era, an age grappling with both scientific revolution and the divine right of kings. Edelinck was deeply admired by his contemporaries for accurately catching those dynamics, the image functioning like the best photograph available at the time. Editor: Looking at it now, knowing something of La Quintinie's place in that world, the picture really deepens. The picture's details provide some insights into the man, but reveal much about the wider political machinery of the time, including the rise of professional status conferred from court service. Curator: A rewarding dive indeed, seeing art as both representation and historical actor helps to illuminate the complex political relationships between society, artists, and influential people of the day. Editor: For me it’s confirmed that a portrait does more than reproduce a likeness, they present the essence of a subject—revealing how figures, both great and small, leave enduring symbols in history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.