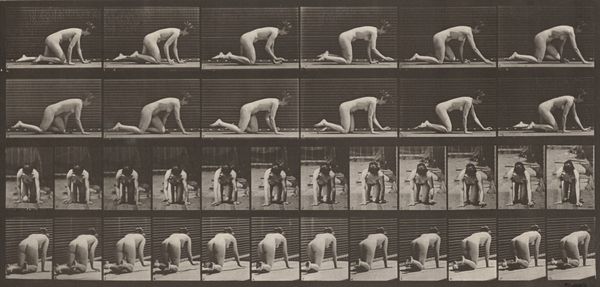

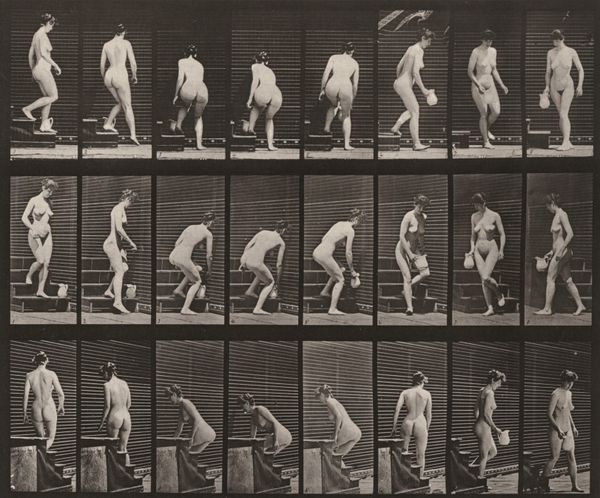

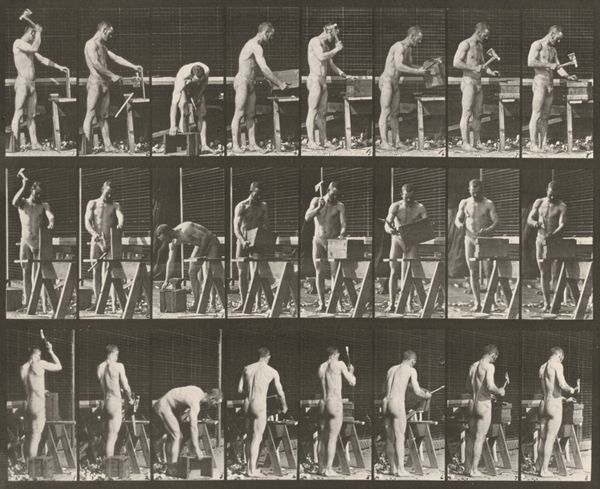

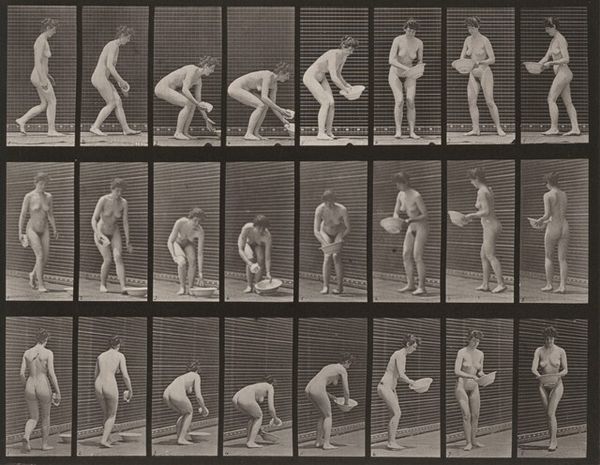

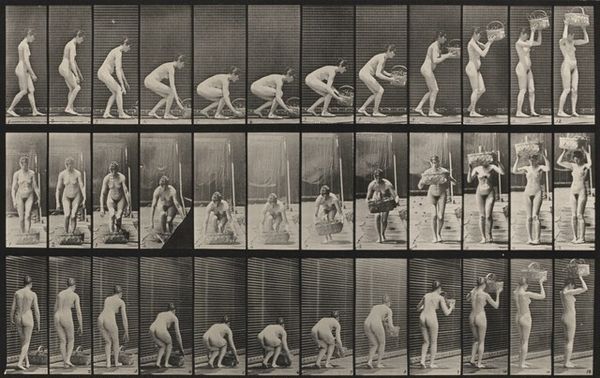

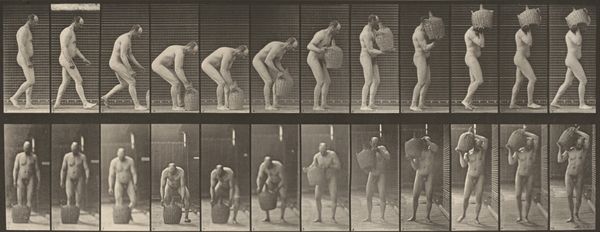

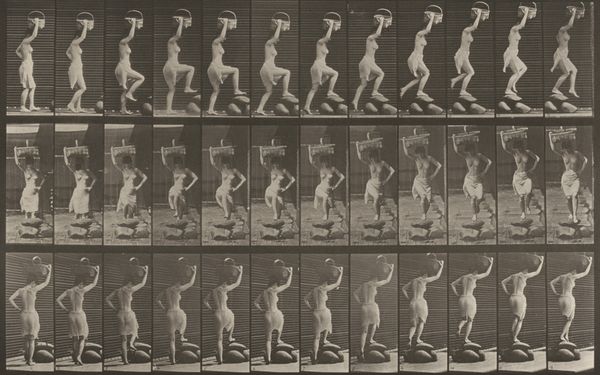

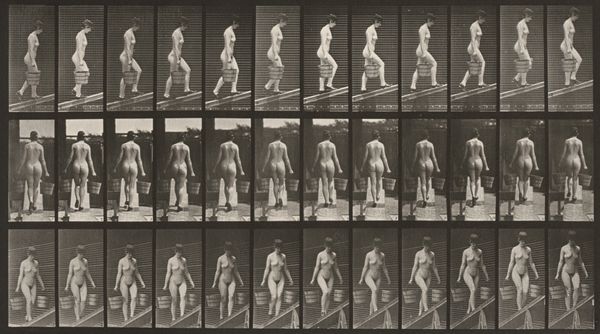

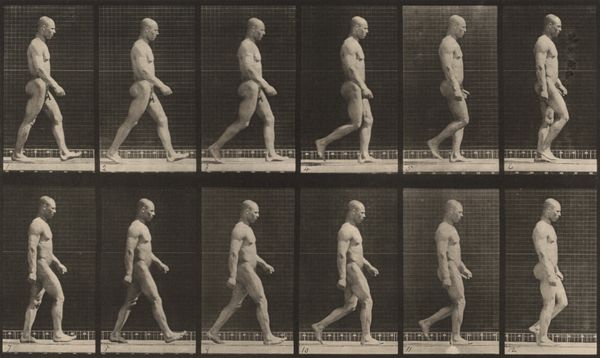

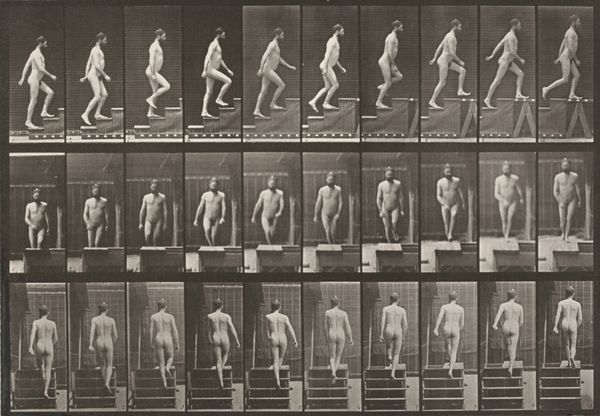

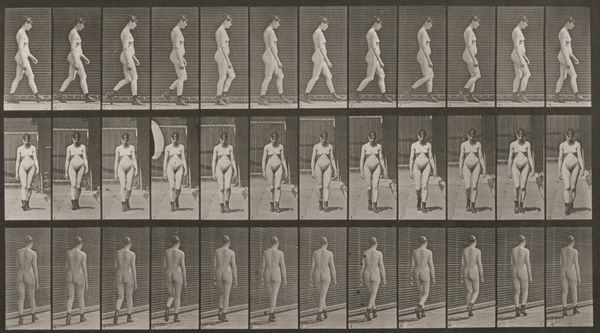

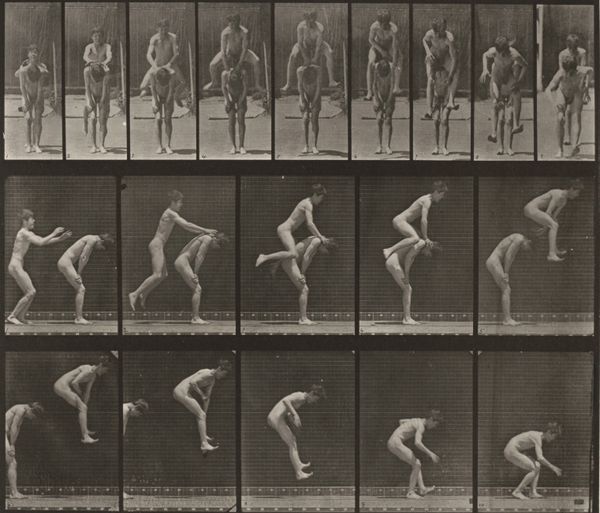

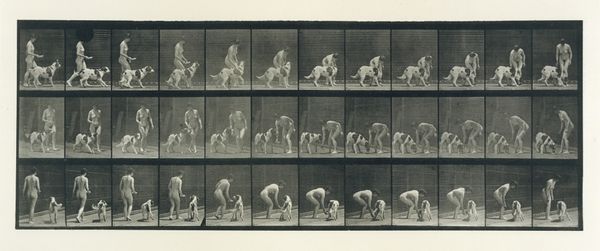

Plate Number 477. Child stooping, lifting a goblet and drinking 1887

0:00

0:00

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

kinetic-art

# print

#

figuration

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: image: 20.8 × 35.3 cm (8 3/16 × 13 7/8 in.) sheet: 47.8 × 60.3 cm (18 13/16 × 23 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Looking at this print by Eadweard Muybridge, titled "Plate Number 477. Child stooping, lifting a goblet and drinking," created in 1887, my first thought is the way the grid organizes the sequential frames of the child's movements. It's quite captivating. What’s your impression? Editor: The initial impact is rather unsettling. There’s an inherent voyeurism at play here. These fragmented moments dissected and displayed—it prompts uncomfortable questions about innocence, observation, and early photographic practices. Curator: Right, well Muybridge's work, and this piece in particular, stems from a deep fascination with capturing and analyzing movement. He used a series of cameras to break down actions into split-second intervals. Think of the equipment, the photographic plates… it all served the purpose of freezing motion. Editor: Indeed, and beyond the technology, we have to consider the social implications. This type of photography intersected with Victorian scientific racism and phrenology. There's the gaze on a child's body, divorced from agency. How does the consumption of these images reflect broader power structures in Muybridge's time? Curator: Well, this image and other photographs were meant for scientific research. They contributed to the development of biomechanics, informing artists and scientists alike on how bodies moved, worked, and were capable of working. Editor: I see it, and, also think we need to acknowledge that "scientific research" doesn't occur in a vacuum. These seemingly objective studies have often perpetuated biases. These representations contributed to the creation and reinforcement of controlling and limiting perceptions that impact that very body in later times. Curator: That's valid. When you look at the silver gelatin printing itself, there's an incredible clarity. Each frame feels almost like a miniature sculpture. We see the shift from high art, and the labor required to make images like this. Editor: Labor is at the center of it, indeed! Thinking about both the physical labor in creating the photograph, from prepping chemicals to the model's work, it invites us to reconsider the value we ascribe to visibility versus real-world experience. Curator: Food for thought. Well, it is images like this by Muybridge, who sought to distill movement that still captivates and challenges us. Editor: Agreed. It's in interrogating these tensions—the scientific aspiration and the cultural baggage—that we can genuinely appreciate the work's multifaceted nature and what continues to make us think about whose image we see when viewing art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.