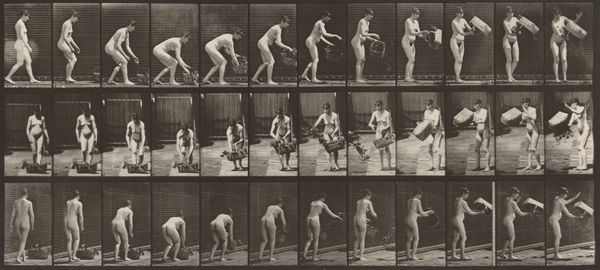

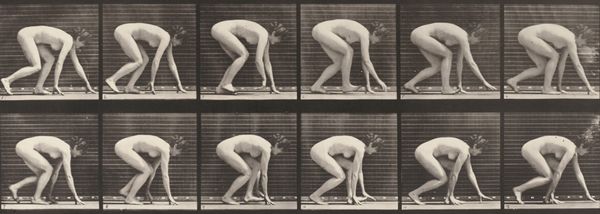

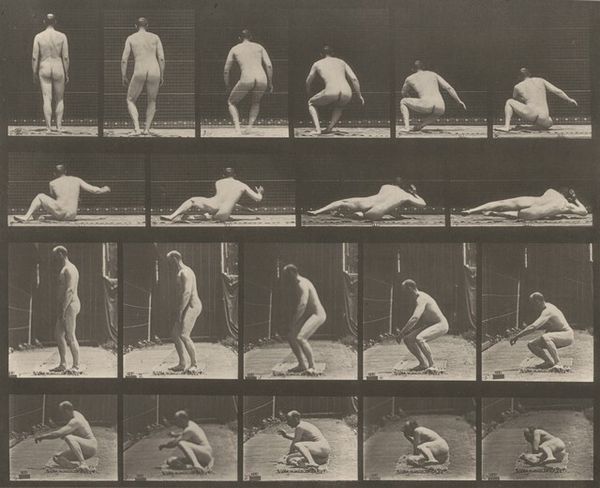

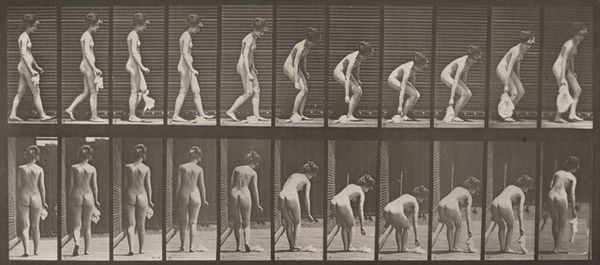

Plate Number 220. Stooping, and lifting handkerchief and turning 1887

0:00

0:00

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

pictorialism

# print

#

neo-impressionism

#

figuration

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

monochrome

Dimensions: image: 15.7 × 45.4 cm (6 3/16 × 17 7/8 in.) sheet: 48.2 × 61.1 cm (19 × 24 1/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

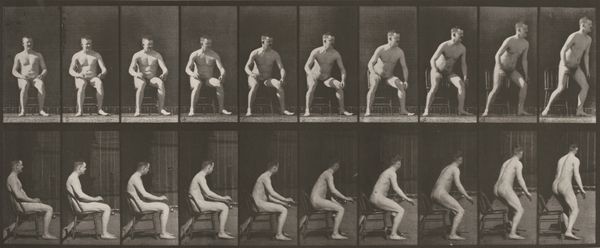

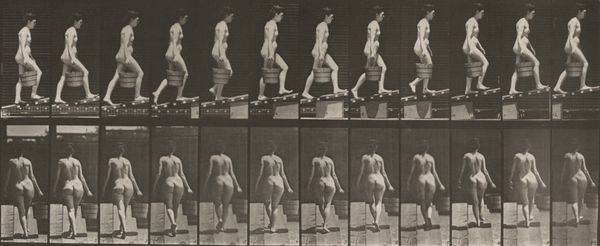

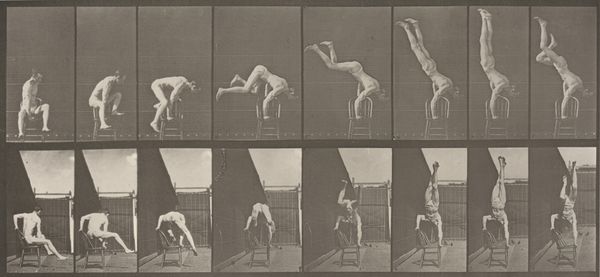

Curator: This is Plate Number 220. Stooping, and lifting handkerchief and turning, by Eadweard Muybridge, created in 1887. It’s a gelatin silver print, part of his series exploring human locomotion. My first impression is the rigidity—the clinical arrangement contrasts with the natural, almost vulnerable human form. Editor: I see it similarly, the rows feel reminiscent of the scientific drive to categorize and dissect that was part of the late 19th-century project. This attempts to deconstruct not just movement, but the very concept of womanhood into component parts that can be understood mechanistically. Curator: Absolutely. Muybridge’s work was fundamentally about understanding the mechanics of movement. Look at how each frame captures a specific moment, broken down, in a time sequence. We should consider that each photograph has been taken in an artificially staged scene, constructed to investigate, step-by-step, a whole process of bodily movement and labor. Editor: It’s also interesting to examine the social context. The figure’s nudity immediately places the image within discourses of both science and art, reminding us of the intertwined histories of the male gaze and objectification, both within art traditions and burgeoning scientific and pseudoscientific disciplines of the time. Her task—picking up a handkerchief—also speaks to the expectation for cleanliness, perhaps echoing then-current bourgeois obsessions with sanitation. Curator: Precisely, and this leads us to understand its mass production. Muybridge intended these photographs to serve a functional, perhaps even pedagogical role, to educate. The materiality is an intentional means to an end. His works were sold as affordable prints and used as tools to be analyzed and manipulated to discover facts about bodies and movements. Editor: Yet, despite the objective pretense, the image itself conveys vulnerability. By stripping down her movement to individual instances, he lays bare some raw human activity to our inspection, which seems oddly clinical. Curator: Perhaps he was ahead of his time! It seems that Muybridge managed to offer tools of technological advancement for a modern understanding of how people worked. Editor: Yes, although viewed now, the stark, systematized recording also provides fodder for a broader critique of how power and scientific ambitions converge in unsettling ways. It certainly forces us to ask about the cost of so-called progress, no?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.