drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

baroque

#

mechanical pen drawing

# print

#

sketch book

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen and pencil

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

cityscape

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

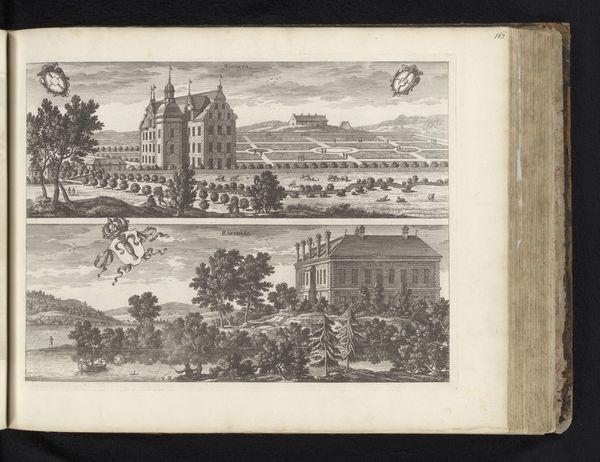

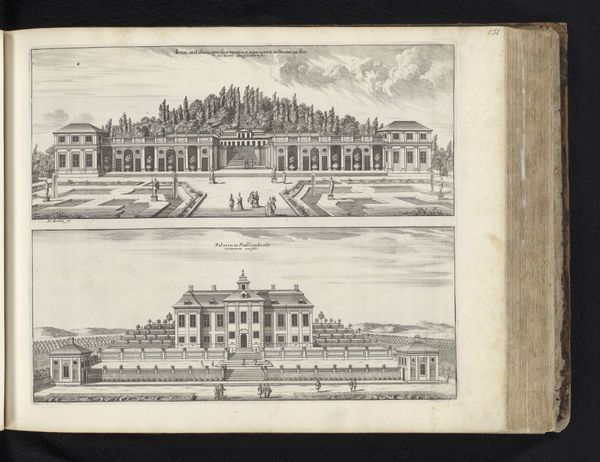

Dimensions: height 272 mm, width 349 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

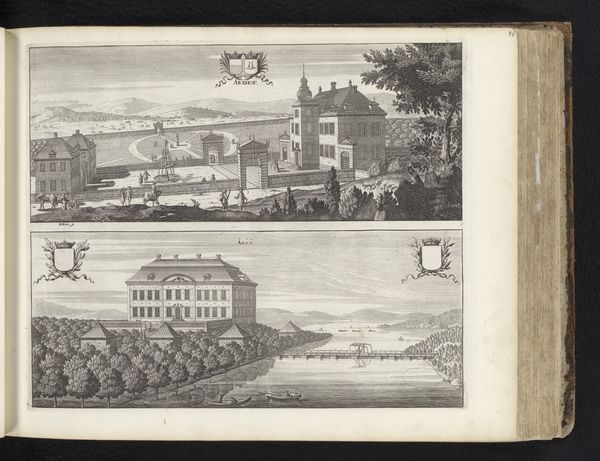

Editor: Here we have Jean Le Pautre's "View of the Årsta Manor and Häringe Castle" from 1670. It’s an engraving, almost like architectural plans but with a dreamlike quality. What do you make of this, particularly the juxtaposition of the two estates? Curator: This engraving invites us to consider the power dynamics embedded within the landscape itself. These aren't just pretty pictures; they're statements of ownership, control, and societal hierarchy. The meticulously rendered estates project an image of wealth and dominance, but at what cost? Consider the labor, resources, and perhaps even the displacement required to create and maintain these idyllic settings. How does this depiction serve to legitimize a specific social order? Editor: That's a fascinating point. I hadn't thought about the social implications so directly. So you're saying the landscape itself becomes a symbol of power? Curator: Absolutely. The manicured gardens, the imposing structures – they speak volumes about the owner's ability to command nature and society. Think about who is included in the landscape and who is noticeably absent. Who is granted access to these spaces, and whose labor sustains them? How does this image reinforce or challenge existing notions of class and privilege? Editor: So looking at the two estates together is like comparing two different displays of power from that time. Curator: Exactly. And by extension, it allows us to think critically about how wealth and power are represented in art and architecture today. Are these just idyllic scenes or loaded representations of societal imbalances? Editor: I see, the print prompts us to look beyond the surface. I definitely learned a lot about this piece today. Curator: Indeed. Art serves as a potent lens through which we can examine the complexities of history, identity, and social justice.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.